This post was created and written in partnership with Hispanic Access Foundation. We would like to thank the Latino community members who contributed their stories to this project.

One in four of all Latinos in the United States live in a county that has experienced a federal disaster declaration for flooding in 2023, according to data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). In contrast, only one in 10 non-Latinos live in those same counties. The startling prevalence of Latino people living in places that have been impacted by floods in a single year highlights the need for solutions to flood risks that can leverage involvement from Latino community leaders and create opportunities for engagement with local, state, and federal resilience programs.

Headwaters Economics and the Hispanic Access Foundation have collaborated on an analysis of Latino experiences with flooding, documenting stories from community members, mapping where Latinos face the highest risks from flooding, and identifying successful strategies for reducing risks. Understanding the unique vulnerabilities of different groups of people, such as Latinos, is critical for implementing effective disaster resilience strategies. This is especially true for places that face vulnerabilities beyond flood risks, such as language barriers, inadequate housing, or local governments that lack the capacity to fully implement solutions.

For this post, “Latinos” includes all people who self-identified as “Hispanic or Latino” in their U.S. Census survey response.

Latinos are more likely to be impacted by floods

Floods impact people differently depending on their exposure to flooding and their ability to prepare, cope, and recover from flooding. As floods become more frequent and severe, the impacts widen existing inequities. Latinos, for example, often struggle to access federal disaster aid after a disaster and are more likely to lose wealth in the long term when compared to White, non-Latino households. In counties that suffered more than $10 billion in disaster-related damages from 1999 to 2013, Latino households lost an estimated $29,000 in wealth – higher losses than other demographic groups.

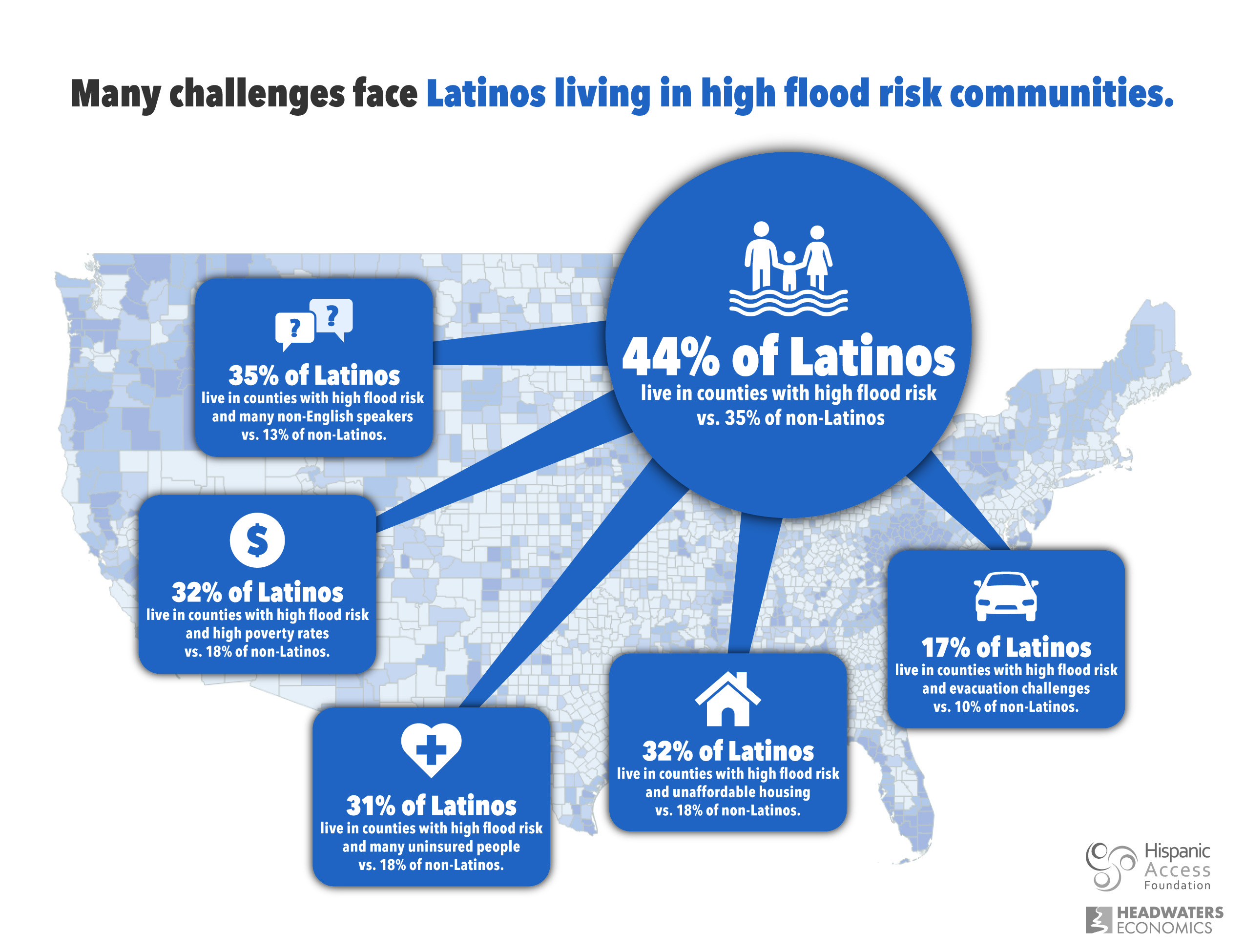

For Latinos, exposure to flood risk is particularly acute. Nationally, 44% of Latinos live in counties with high flood risk, as opposed to 35% of non-Latinos. Decades of land use decisions and infrastructure investments (or lack thereof) have shaped this unequal exposure. Additionally, Latinos are often left out of disaster and evacuation planning due to language barriers, differences in access to information, and a lack of trust in interacting with the government.

The interactive map below shows where Latinos face high risks from flooding. The map can help identify places that need more resources, technical assistance, and long-term investments to address flood risk and protect community members. Filter counties by the percent of people who are Latino, and hover over a county to view population characteristics that can compound vulnerabilities.

The map demonstrates the wide variety of places where Latinos face high flood risks. Counties with high flood risk and large shares of Latino people range from hurricane-prone counties – such as Miami-Dade County, Florida, and Cameron County, Texas – to counties with large agriculture sectors, such as Sonoma County, California, and Chelan County, Washington. Other areas with large shares of Latino people and high flood risk may be more unexpected, such as urbanized Cook County, Illinois (where Chicago is the county seat) and tourism-dependent Teton County, Wyoming, home of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort.

Gisel Garza

American Forests Project Manager,

Lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas

“In the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, where many impoverished families live in colonias (informal settlements), floods can be devastating for victims in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, and for months or years after. Homes and vehicles are destroyed, and many go without essential electricity and other services after a flood. Health is put at risk as residents endure high heat, lack of food and water, and are increasingly susceptible to mosquito bites that carry vector-borne diseases like Chikungunya and Zika. Colonias are areas that are often unpaved, don’t have as good access to electricity, water, wi-fi, and are outside of city limits. The harmful effects of flooding are both short and long term.”

Many challenges face Latinos living in high flood risk communities

Many Latinos live in high flood risk counties where people have additional vulnerabilities due to language barriers, inadequate housing, lack of political representation, immigration status, and limited access to resources. While Hispanics and Latinos are lumped together in datasets, their experiences with, and vulnerabilities to, flooding are diverse. For instance, Latinos who are recent immigrants to the United States or are undocumented tend to have higher levels of vulnerability and often struggle the most to recover after a flood.

In many places with both high flood risk and high social vulnerability, Latinos tend to make up a larger proportion of the population than non-Latinos.

See Data Sources & Methods for definitions of flood risk and socioeconomic characteristics.

Claudia Pineda Tibbs

Sustainability Manager,

Monterey Bay Aquarium,

Focus Community: Pajaro, California

“When a flood occurs in a place with compounding vulnerabilities, it creates social and economic impacts that ripple throughout the community in both the short and long term. In Pajaro, California, 92% of the residents identify as Hispanic or Latino. When a critical but poorly maintained levee failed during an intense storm in 2023, the entire community flooded and thousands of residents had to evacuate. The flooding put a spotlight on the decades of inequity in the agricultural region, where migrant farmworkers have long been marginalized. The farmworkers face dual crises after a disaster – the flood not only destroyed the workers’ homes but also their livelihoods, as the farms where they worked were also underwater for months. The displacement of over 2,000 workers resulted in many closed businesses, complicating the recovery process and resulting in long-term, regional economic losses.”

Read more about the flooding in Pajaro, California in the Santa Cruz Local, Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times.

Community solutions in action

Latinos across the United States are working to address flood risk in creative and innovative ways. In Arizona, Nebraska, California, and elsewhere community members are applying a wide range of solutions on the ground to strengthen Latino communities’ resilience to flooding.

Investing in green infrastructure

Nueva Esperanza Church: Pima County, Arizona (38% Latino)

Since its founding nearly 75 years ago, the Nueva Esperanza Church in Tucson, Arizona, has experienced repetitive flooding. To address this risk, the city and the community partnered to install “green infrastructure” landscaping to reduce stormwater run-off and better absorb floodwater. They designed and built grass-lined basins that can store more than 3,000 gallons of water during periods of heavy rainfall. These infiltration basins reduce the risk of flooding and provide water for irrigating the church’s gardens.

Restoring access to natural areas

The Whitewater Preserve: Riverside County, California (50% Latino)

The Wildlands Conservancy’s Whitewater Preserve in southern California is approximately 150 miles from the U.S. – Mexico border. In 2023, the preserve experienced devastating flooding from Tropical Storm Hilary. In addition to destroying critical road infrastructure, many staff were displaced from their homes for months. Road repairs were prioritized, allowing Latino employees to return to the preserve to work on areas that were heavily impacted by the storm. In partnership with the county, the Conservancy is working to restore access to the preserve for local Latino and non-Latino residents.

Preserving affordable housing

Regency Mobile Home Park: Dodge County, Nebraska (14% Latino)

In 2019, a flood damaged more than 1,500 homes and buildings in Fremont, Nebraska, including a mobile home park that was critical housing for immigrant and Latino residents. In response, a long-term recovery group spearheaded by United Way raised private funds and hired contractors to fix the homes and remediate mold. This was a key strategy for preserving the community’s economy and social fabric as the community has limited workforce housing. In the longer term, the county is coordinating mitigation projects across the area to ensure the community is more resilient to future flooding.

Policy recommendations to help create more equitable and resilient communities

Recent floods, from Pajaro, California, to Houston, Texas, highlight the unique exposure and vulnerabilities that many Latinos have to disasters. Yet federal policies and programs often fail to account for the unequal impacts of flooding. As flooding becomes more frequent and severe, changes to local, state, and federal disaster policies are needed to create more equitable and resilient communities.

The following policy and administrative recommendations can help improve outcomes for Latinos and other racial and ethnic groups that are disproportionately impacted by flooding:

1. Address cultural barriers to accessing resources.

Latino communities often struggle to access resources to better prepare for or recover from disasters. Oftentimes the tools to reduce flood risk and address impacts exist but fail to reach those who need them most. More deliberate planning and outreach can help. For example, after a disaster preparedness training series was conducted by the American Red Cross and Hispanic Access Foundation, the Red Cross saw a threefold increase in downloads of their Spanish-language emergency application.

Local, state, and federal agencies can improve their emergency response and preparedness strategies by investing in bilingual materials and creating ongoing opportunities to build trust and relationships between people and government agency staff.

2. Use disaster policies to address the root causes of vulnerabilities.

Many communities with high exposure to flooding and high levels of social vulnerability have a history of disinvestment that has exacerbated their risks. Communities that have struggled to access state and federal funding are more likely to have inadequate or poorly maintained infrastructure that heightens their chance of flooding.

Local, state, and federal agencies should prioritize strengthening overall community wellbeing and creating economic opportunity. Housing is one critical element. Government agencies can address the root causes of vulnerabilities by investing in creating and preserving durable, affordable housing.

3. Invest in risk-reduction strategies in places with high exposure and vulnerability

Many local governments in communities with high flood risk and high social vulnerabilities lack the capacity, including the staff and resources, required to plan and implement solutions. These communities need resources and capacity building to be able to proactively address their flood risk and strengthen resilience to future disasters.

State and federal government agencies can help lower-capacity communities by providing them with technical assistance, helping to coordinate regional or watershed collaboratives, and providing long-term, predictable revenue for resilience investments.

Learn More

Data sources & methods

- Flood risk data:

- First Street Foundation provided flood data from their Flood Factor platform for use in this research. Flood risk is defined as the percent of properties within each county that have a >1% chance of a flood in a given year. We ranked each county’s flood risk relative to the entire nation. For example, counties in the 0 to 49th percentile have lower flood risk than 50% of U.S. counties.

- Counties above the 50th percentile have higher flood risk than 50% of U.S. counties and are considered “high risk.”

- Socioeconomic data:

- The socioeconomic variables are from U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS).

- Latinos are those who self-identified as “Hispanic or Latino” in their survey response.

- We used the latest release of the ACS five-year estimates (2017-2021). These estimates represent data collected over the five-year period of time.

- The primary advantage of using multiyear estimates is the increased statistical reliability of the data for less-populated areas and small-population subgroups.

- ACS is a survey of residents with reported margins of error based on the number of respondents. The margin of error as reported by ACS is displayed in the mouse-over tooltip for each county.

- Infographic data:

- Counties with many non-English speakers are defined as those where the percent of people with language barriers exceeds the national median.

- Counties with high poverty rates are defined as those where the percent of families in poverty exceeds the national median.

- Counties with many uninsured people are defined as those where the percent of people without health insurance exceeds the national median.

- Counties with unaffordable housing are defined as those where the median home value exceeds the national median and more than 1/3 of households pay unaffordable rent (rent exceeding 30% of household income).

- Counties with evacuation challenges are defined as those where the percent of households with no car exceeds the national median.

Acknowledgments

The team at Hispanic Access Foundation, including Shanna Edberg, Vanessa Muñoz and Juan Rosas, contributed knowledge and expertise to this project. Hispanic Access Foundation establishes bridges of access that provide a path for the development and rise of Latino leaders and elevates their voices in areas where they are underrepresented.