Headwaters Economics has analyzed the latest project selections announced by the Federal Emergency Management Agency for its Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant program. This is the third year of selections for BRIC funding, a program that supports projects across the United States that reduce natural disaster risks and build climate resilience.

This year’s BRIC grants total nearly $2.3 billion, a marked increase from the program’s $791 million (in 2022 dollars) in inaugural funding. BRIC has designated money for state allocation projects, tribal projects, management costs, and competitive national grants. In this year’s national competition, FEMA selected 124 projects in 36 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, and the Karuk Tribe in California.

Among our key findings:

- The geographic distribution was very uneven. Half the states collectively received less than 5% of this year’s BRIC funding.

- 78% of this year’s BRIC funding went to East and West Coast states, compared to 22% that went to interior and Gulf Coast states.

- One-quarter of the projects selected in this year’s national competition were in counties that had received a BRIC grant in previous years.

- Over the three years of the BRIC program, only 13% of counties (18 of the 138 counties) with funded projects have Rural Capacity Index scores below the national median.

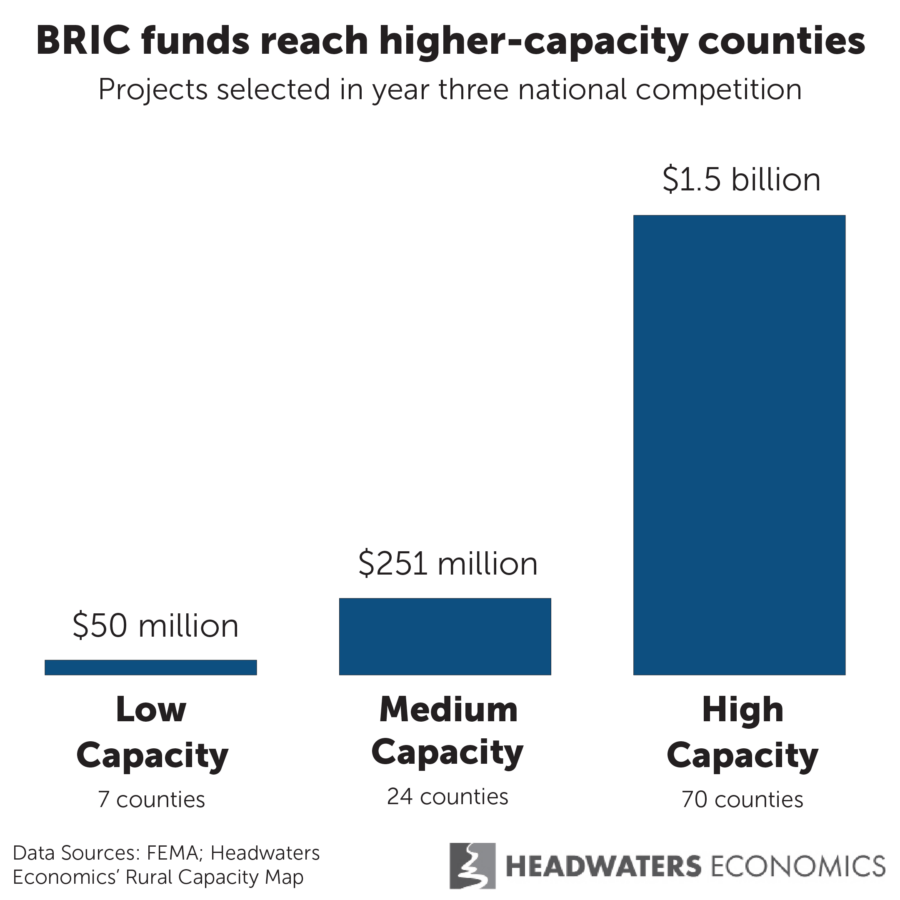

- In this year’s national competition, 3% of funding ($50 million) went to projects in low-capacity counties, and 83% ($1.5 billion) went to projects in high-capacity counties.

BRIC funds innovation in climate risk reduction

Projects funded through FEMA’s BRIC program are critical investments in the country’s climate resilience.

For example, in its third year and latest round of funding, FEMA selected five California projects, totaling $126 million, to strengthen wildfire resilience, including home hardening. Retrofitting and hardening homes is a key strategy for reducing wildfire risk but to date these initiatives have not received significant federal funding. The BRIC awards to California mark a shift in wildfire mitigation funding that recognizes the increased need to manage the built environment to help ensure homes are better prepared for wildfires.

This year’s national competition also included funding for two mobile home park buyout projects, a $6 million project in Yakima, WA and a $10 million project in Pierce County, WA. Mobile home parks are frequently located in high flood risk areas and house some of the country’s most socially vulnerable people. However, communities have struggled to secure funding for solutions that improve safety for mobile home park residents. BRIC’s commitment to addressing mobile home park vulnerabilities is notable in that it both acknowledges the problem and helps illustrate the amount of funding needed to help communities address it.

Importantly, FEMA received more than $4.6 billion in funding requests in Year 3 but was only able to fund $2.3 billion. This demonstrates that the demands for mitigation far outstrip FEMA’s current budget. This funding gap reinforces the need for an increase to BRIC’s budget to help communities and regions strengthen resilience to disasters.

Geographic distribution of BRIC grants

In a pattern that reinforces previous years’ distributions, 78% of this year’s funding went to East and West Coast states, compared to 22% of funding that went to interior and Gulf Coast states. Every state except for West Virginia received funding. However, coastal states continue to receive the largest and highest number of BRIC grants. Collectively, the bottom 25 states based on distributions received less than 5% of all BRIC funding.

Many states have repeatedly failed to secure substantial BRIC funds, while other places continue to secure money year after year. For the projects preliminarily selected in the Year 3 national competition, 25% of them were in counties that had received a BRIC grant in either the Year 1 or 2 national competitions. Across the three fiscal years, the San Francisco and New York metro areas have been the most successful at securing BRIC funding.

Although interior states were selected to receive a much smaller share of BRIC funds, the expanded BRIC budget – $2.3 billion in Year 3 versus $791 million (in 2022 dollars) in Year 1 –made a difference. For instance, in Year 1, Great Plains states (ND, SD, NE, KS, and OK) secured less than 1% of BRIC funding, approximately $5.2 million (in 2022 dollars). In Year 3, these states still struggled to secure a large share of the funding, managing only 1.5%. However, with the expanded budget this resulted in more than six times the amount of funding from 2020 levels, or approximately $32.8 million in grants.

The chart below highlights the amount of total BRIC funding, including state, tribal, management costs, and national competition awards, that each state has received per funding round.

Capacity barriers prevent access to BRIC

FEMA BRIC applications are complicated and time consuming to develop and submit. The communities that are most successful at securing BRIC grants tend to be higher capacity, larger cities.

In the graph below, we compare Rural Capacity Index scores to states with BRIC applications that were selected for further review. In Year 3, states with more high-capacity communities—those with key local government positions and expertise—were more likely to have successful applications. This pattern is consistent with previous years’ distributions as well.

In the national competition for Year 3, seven low-capacity counties received national competition grants totaling $50 million. In comparison, 70 high-capacity counties secured competitive grants totaling $1.5 billion in BRIC funding. Counties with higher capacities were noticeably able to secure larger BRIC distributions in the Year 3 national competition compared to lower-capacity counties. Thus, while more communities may be benefiting from BRIC, smaller and lower-capacity communities are struggling to secure larger grant funding – if any.

Over the three years of the BRIC program, only 13% of counties (18 of the 138 counties) with funded projects have Rural Capacity Index scores below the national median.

Strategies to improve access to BRIC and build capacity

While BRIC has been successful at funding critical mitigation projects, the program is not reaching many rural, lower-capacity places that face natural disaster risks.

FEMA and other federal agencies have demonstrated a commitment to improving socioeconomic and geographic equity outcomes. Below are promising strategies to improve access to BRIC and to build overall capacity for mitigation efforts in the United States.

Solutions to improve access to BRIC and other federal mitigation programs:

- Simplify applications. BRIC is a complicated application that requires significant resources and expertise to be successful. A simplified application would enable more rural, disadvantaged, and lower-capacity communities to apply. The USFS’s Community Wildfire Defense Grant tool offers an example of one federal strategy being used to reduce the administrative burden. This free online resource informs communities whether they are eligible for the grant and, if so, provides the data they will need to fill out the application.

- Reduce or waive grant match requirements for more communities. Local match requirements prevent many rural and low-capacity communities from applying for federal grants. While BRIC offers a reduced local match for small, economically disadvantaged communities, the eligibility requirements are too restrictive. Reducing and waiving the local match requirements for more communities would make the program more accessible. State governments can further help lower-capacity communities by creating programs to assist with local match requirements for federal grants. For example, Texas’s Infrastructure Resiliency Fund provides funding that communities can use to pay for federal local match costs.

- Increase state allocations. FEMA has increased the state allocation funding pool from $678,000 (in 2022 dollars) per state in its first year to $2 million in its third year. This has enabled many smaller but critical mitigation projects – such as improving culverts in Missouri and retrofitting wastewater lagoons in North Dakota – to be funded without having to compete at the national level. Increasing the state allocation portion of BRIC would enable more of these types of projects and expand the geographic reach of BRIC.

- Create more technical assistance for low-capacity communities. BRIC’s direct technical assistance program is providing critical services to rural and lower-capacity communities, but its reach is limited. FEMA needs more resources and staff to meet the need. FEMA could also experiment with partnering with nonprofit organizations, regional hubs, and navigator programs to ensure that communities with limited resources are able to access federal funding programs.

Solutions for building capacity:

- Invest in local and state mitigation capacity. States play an outsized role in BRIC funding distributions, but many state agencies lack the capacity to assist their rural, disadvantaged, and lower-capacity communities. FEMA’s Emergency Management Performance Grant is used by many states to fund local and state emergency management personnel and mitigation efforts, but funding levels have not kept up with needs and are often unpredictable from year-to-year. Congress can build local and state capacity for emergency management and mitigation by increasing funding for this program and authorizing it for multiple years.

- Fund regional organizations and promote multi-jurisdictional projects. Funding regional organizations and projects that leverage urban-rural partnerships to decrease disaster risk can strengthen capacity in low-capacity communities. Regional approaches often face high organizational expenses due to the time and cost of coordinating across government jurisdictions and multiple stakeholders. FEMA and other federal agencies can support these critical approaches by offering more operational funding. State governments can also help support and coordinate regional approaches by providing funding, staff, and other resources.

- Address the root causes of low capacity. Low-capacity communities have often experienced decades of disinvestment, resulting in inadequate infrastructure, economic dependence on narrow sectors, and local governments that can barely meet community needs and day-to-day operations. By prioritizing projects that address the root causes of vulnerability and low capacity, BRIC and other federal funding programs can help communities address inequities within their community, generate predictable local revenue needed to maintain infrastructure and adaptation projects, and strengthen trust in local government. Through eligibility and scoring criteria, FEMA can encourage projects that create long-term economic benefits through new jobs, affordable housing, and local amenities like outdoor recreation.

- Expand and diversify mitigation funding. This year’s distributions of BRIC funds clearly demonstrate that a larger budget ($2.3 billion) expands the geographic reach of mitigation programs. However, many rural and lower-capacity communities will continue to struggle to access funding from competitive grants. FEMA and other federal agencies can address these equity issues by allocating mitigation funding through other non-competitive mechanisms such as direct allocations, formula grants, and block grants.

Data sources and methods

Data Sources

This research investigates projects that FEMA has preliminarily selected and identified for further review. These applications will go through additional reviews before being awarded funds.

BRIC application and funding data are from FEMA for fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2022. Data include the state allocations, tribal set-aside, and national competition applications. Data do not include the U.S. territories.

To compare funding between years, all dollars have been adjusted for inflation and reflect 2022 dollars.

Data about community capacity are from Headwaters Economics’ Rural Capacity Map.

Proposals to BRIC funded through Flood Mitigation Assistance

This analysis does not include proposals funded by FEMA’s Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) program. FMA grants are released at the same time as BRIC grants. Many communities apply to both BRIC and FMA programs using the same application. If a project is selected, FEMA decides which funding pool to use. For Fiscal Year 2022, FMA grants totaled more than $711 million. The top five recipients of FMA grants were Texas ($206.6 million), Louisiana ($148.3 million), North Dakota ($70.2 million), California ($58.9 million), and New Jersey ($50.8 million).