The federal government allocates vast amounts of resources to protecting homes in wildfire-prone areas. Wildland firefighting costs associated with home protection are high and rising due to climate change and ongoing development in hazardous areas.

New research has mapped the costs of protecting homes from wildfires and shows that the cost of wildfire protection per home is highest in rural parts of the western United States where housing density is relatively low.

In these areas of low housing density and high wildfire risk, upfront investments in mitigation, including the use of fire-resistant building and landscaping materials, could be highly cost effective—saving lives and property, and reducing fire suppression costs.

Protecting homes from wildfires is expensive

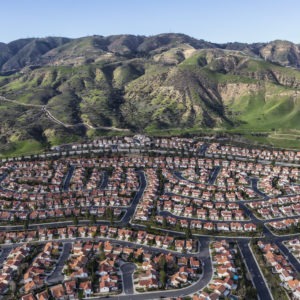

Rapid suburban and exurban home development starting in the second half of the 20th century has occurred in areas bordering public lands. This has placed an increasing number of homes and lives in areas with high wildfire risk. Consequently, there is social and political pressure on federal and state agencies to safeguard lives and property while also protecting natural resources, forest health, critical watersheds, or other values at risk. Across all levels of government, particularly state and federal levels, land management agencies assume responsibility and incur high costs for protecting homes and neighborhoods from wildfires.

The cost of wildfire protection per home is highest in rural areas

New research from economists Patrick Baylis and Judson Boomhower has mapped the federal costs of protecting homes from wildfires across the 11 western states. Their findings are based on comprehensive data on firefighting expenditures from 4,665 fires affecting nearly 9 million homes and accounting for more than $13 billion in suppression costs from 1995 to 2016 (see Data Sources & Methods below).

The map below, representing Baylis’ and Boomhower’s findings, illustrates where the federal government is spending money to protect homes from wildfires and provides estimates of costs for home protection over the life of the home should trends continue. It shows that expected wildfire protection costs, on average, are highest in rural parts of the West where home density is relatively low.

The average expected protection costs are shown for all single-family homes per 15-km cell. Costs range from $1 per home to greater than $50,000 per home and vary with wildfire hazard potential, density development, and other factors. The relatively low cost estimates for Colorado reflect fewer costly, large fires in that region during the historical sample period analyzed in the paper (1995 to 2016).

The analysis also demonstrates which states have the largest number of homes with high expected protection costs if a wildfire occurs. The table below shows the total number of properties in each state that are estimated to have protection costs of more than $10,000 per home.

Number of properties in locations with extremely high wildfire protection costs.

| State | # Properties |

|---|---|

| California | 138,911 |

| Montana | 79,509 |

| Idaho | 77,942 |

| Washington | 56,267 |

| Oregon | 55,062 |

| Utah | 28,672 |

| Arizona | 14,674 |

| New Mexico | 14,129 |

| Nevada | 10,739 |

| Wyoming | 3,868 |

| Colorado | 3,152 |

California has more than 138,000 properties in areas where wildfire protection costs are expected to exceed $10,000 per home over the life of the home. Montana and Idaho each have more than 75,000 properties in areas where lifetime protection costs are expected to exceed $10,000 per home if one or more wildfires occur.

Community investment is needed now

While measures that reduce wildfire risk should be implemented in all high wildfire hazard areas, they may be especially cost effective in areas where expected home protection costs are highest. Every western state has neighborhoods where an upfront investment in mitigation would go a long way in reducing response and recovery costs paid by taxpayers.

Fortunately, several cost-effective solutions can make homes safer from wildfires. They should be prioritized and integrated into legislation. Investment in neighborhood design, home mitigation, wildfire-resistant construction and landscaping, evacuation, and land use planning are essential.

Specifically, communities need support and funding for:

- Land use planning and development of community planning documents;

- Enacting and improving building codes to integrate wildfire mitigation measures into site design and construction in wildfire-prone areas;

- Retrofitting homes, improving landscaping and property maintenance, and modifying neighborhood layout to increase wildfire resilience.

We must start investing in communities now to create homes and neighborhoods better adapted to increasing wildfire risks.

Data Sources and Methods

Headwaters Economics collaborated with Baylis and Boomhower to represent their dataset in this post.

Estimated Wildfire Protection Costs

Baylis and Boomhower’s research compiled parcel-level data for single family homes in the West with firefighting expenditures from each major federal land management agency, resulting in the most comprehensive dataset on firefighting expenditures yet. Their final data set included 4,665 fires that occurred between 1995 and 2016 and accounted for $13.2 billion of suppression costs. They linked the fires to 8.6 million homes in the WUI in 11 western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). They also considered suppression data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Inspector General in a 2006 Audit Report, Forest Service Large Fire Suppression Costs.

For each of the 8.6 million homes, the researchers calculated annualized “realized” protection costs that represent the historical cost of protecting the home from wildfires. In their empirical regression analysis, Baylis and Boomhower identify the degree to which incident-level firefighting expenditures increase when homes are located in harm’s way.

Realized protection costs were calculated by allocating the total expenditures dedicated to defending homes during each observed fire across individual homes and then summing these totals for all historical incidents. In short, these realized protection costs are the best estimate of what has been spent historically to protect a given home. Realized costs are then extrapolated to estimate “expected protection costs” by averaging realized costs over similar-risk groups of homes. These expected protection costs represent expected government expenditures for home protection over the life of the home should trends continue. Full methodologies are described in detail in Appendix C in Baylis and Boomhower’s published manuscript.

The researchers focused on single-family homes in the West and included topography and weather conditions in their calculations. They considered fires 300 acres or larger.

Their model generated a 15-km grid for the 11 western states that estimates the total protection costs. We assigned each 15-km grid to a county. Grids that overlapped multiple counties were assigned to the county where the majority of the grid overlapped. The expected protection cost for all grids in each county were then summed.

Research Conclusions

Among their research conclusions, Baylis and Boomhower found:

- Fire protection costs can exceed 20% of home value in the West. Half of the homes in high wildfire risk areas in the West have expected protection costs of $2,300 or less. However, 5% of homes have costs nearing $12,000, and 1% of homes have costs exceeding $38,000, according to the analysis. These estimates include expenditures for equipment, firefighter salaries, aviation, and other related home protection costs.

- Higher protection costs are associated with higher fire risk areas. Average home protection costs are clearly linked to the local wildfire hazard potential. According to the research, expected protection costs are highest in Northern California, central Oregon and Washington, Idaho, and western Montana because those areas are sparsely populated and have many areas of high fire hazard. In these remote areas, protection costs can be tens of thousands of dollars per home.

- Protection costs decrease as development density increases. Residential development dramatically increases firefighting costs. The presence of just one to 32 homes almost doubles expenditures on a fire. However, once a development reaches a relatively moderate density (100-300 homes), additional homes have little effect on costs. That is, the cost of protection per home does not increase significantly once the density of homes has reached a particular threshold. The research findings indicate the cost of protecting hundreds of homes in harm’s way is not significantly more than protecting dozens of homes.

Baylis, Patrick, and Judson Boomhower. 2023. “The Economic Incidence of Wildfire Suppression in the United States.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 15 (1): 442-73.

Demographic Data

Demographic data in the visualization above are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey five-year average for 2017-2021.

Wildfire Risk Data

Wildfire Risk data in the visualization above are from Wildfire Risk to Communities and represent the risk to homes ranked against other western U.S. communities and within each state.

Limitations

The analysis in this post is based on a model of historical data and modeling assumptions, and thus does not perfectly predict future outcomes. The relatively low cost estimates for Colorado reflect fewer costly, large fires in that region during the historical sample period analyzed in the paper (1995 to 2016).

For questions and inquiries regarding methodologies and analysis of federal protection costs, please contact Patrick Baylis at patrick.baylis@ubc.ca and Judson Boomhower at jboomhower@ucsd.edu.

Acknowledgments

In addition to their valuable research data, Patrick Baylis and Judson Boomhower contributed knowledge and technical expertise to this project.