Increasing home loss and growing risks require reevaluating the wildfire crisis as a home-ignition problem and not a wildland fire problem. A home’s building materials, design, and nearby landscaping influence its survival. Together with the location, arrangement, and placement of nearby homes, constructing a wildfire-resistant home is critical in light of rising wildfire risks. This report compares the cost of constructing a home to three different levels of wildfire resistance in California.

California is a leader in the country with a statewide building code and other property-level vegetation requirements addressing wildfire impacts to the built environment. Applicable to all new developments located in State Responsibility Areas (SRAs) and the highest fire severity zones in Local Responsibility Areas (LRAs), California’s Building Code Chapter 7A is intended to reduce the vulnerability of homes to wildfire.

Yet given the magnitude of California’s wildfire risks and increasing home development in wildfire-prone areas, constructing a home beyond Chapter 7A requirements may be needed to ensure greater wildfire resistance. Understanding the comparative costs of wildfire-resistant home construction in California can inform future wildfire policy and decision-making.

This report compares the costs for constructing three different versions of a wildfire-resistant home in California:

- Baseline home compliant with the minimum requirements of Building Code Chapter 7A;

- Enhanced home augmenting Chapter 7A requirements with a vertical under-deck enclosure around the perimeter of the deck and a noncombustible zone around the home (0 to 5 feet), including under the deck and extending five feet out from the deck perimeter; and,

- Optimum home constructed to the most stringent, fire-resistant options (e.g., use of a noncombustible material), or in some cases, a “Code plus” option (an option not currently included in Chapter 7A). Optimum performance levels were selected based on recent research findings and best judgment.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Baseline, Enhanced, and Optimum strategies to reduce the vulnerability of homes to wildfire were analyzed in response to recent proposed initiatives in California. In February 2022, the California Department of Insurance, in partnership with the California Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES), California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE), the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, and the California Public Utilities Commission, launched the Safer from Wildfires framework, an approach to provide homeowners with a list of recommended actions to reduce the risk of homes and properties.

Outside state government, the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) released Wildfire Prepared Home™—a designation program certifying that a home meets the mitigation requirements associated with Safer from Wildfires. The Enhanced wildfire-resistant home described in this report is consistent with the IBHS Wildfire Prepared Home designation.

Due to the variability in California’s geography, homeowner preferences, and market trends, costs were compared and analyzed for homes in both northern and southern California. The focus of this report is on construction costs for ignition resistance and does not address vegetation management beyond the five-foot perimeter around the home and under the footprint of any attached deck.

This report expands on a 2018 study conducted by Headwaters Economics and IBHS that assessed costs for wildfire-resistant construction in southwest Montana. Findings from both reports contribute key insights for policies regarding the economic barriers and opportunities for creating fire-adapted communities.

Wildfire-Resistant Home Construction Costs

Building materials and assemblies for five primary home components were considered, including:

- Roof – roof covering, vents, roof edge, and gutters (including gutter covers and drip edge)

- Under-eave area – eaves, soffit, and vents

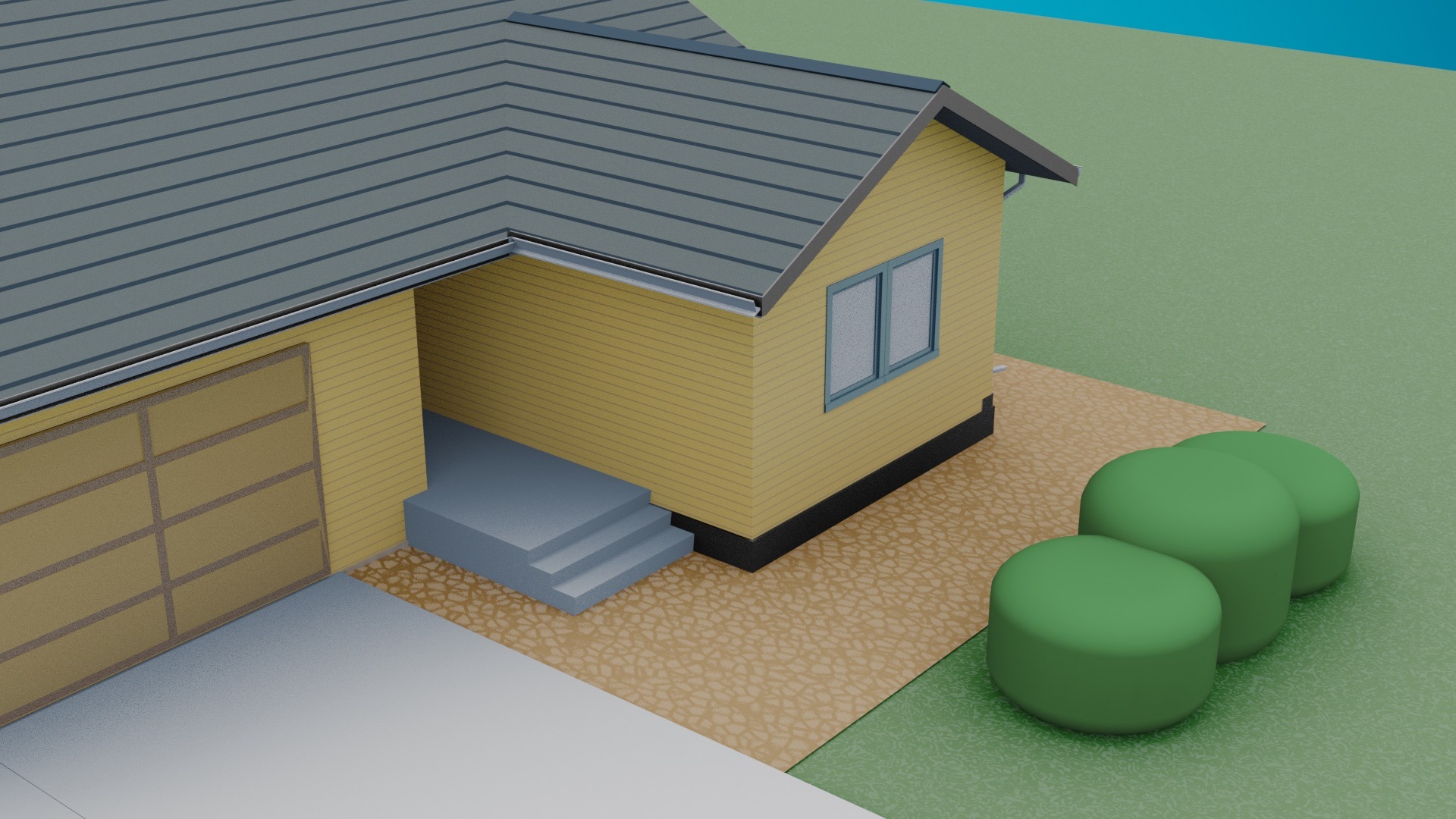

- Exterior wall – siding, windows, doors, trim, and vents

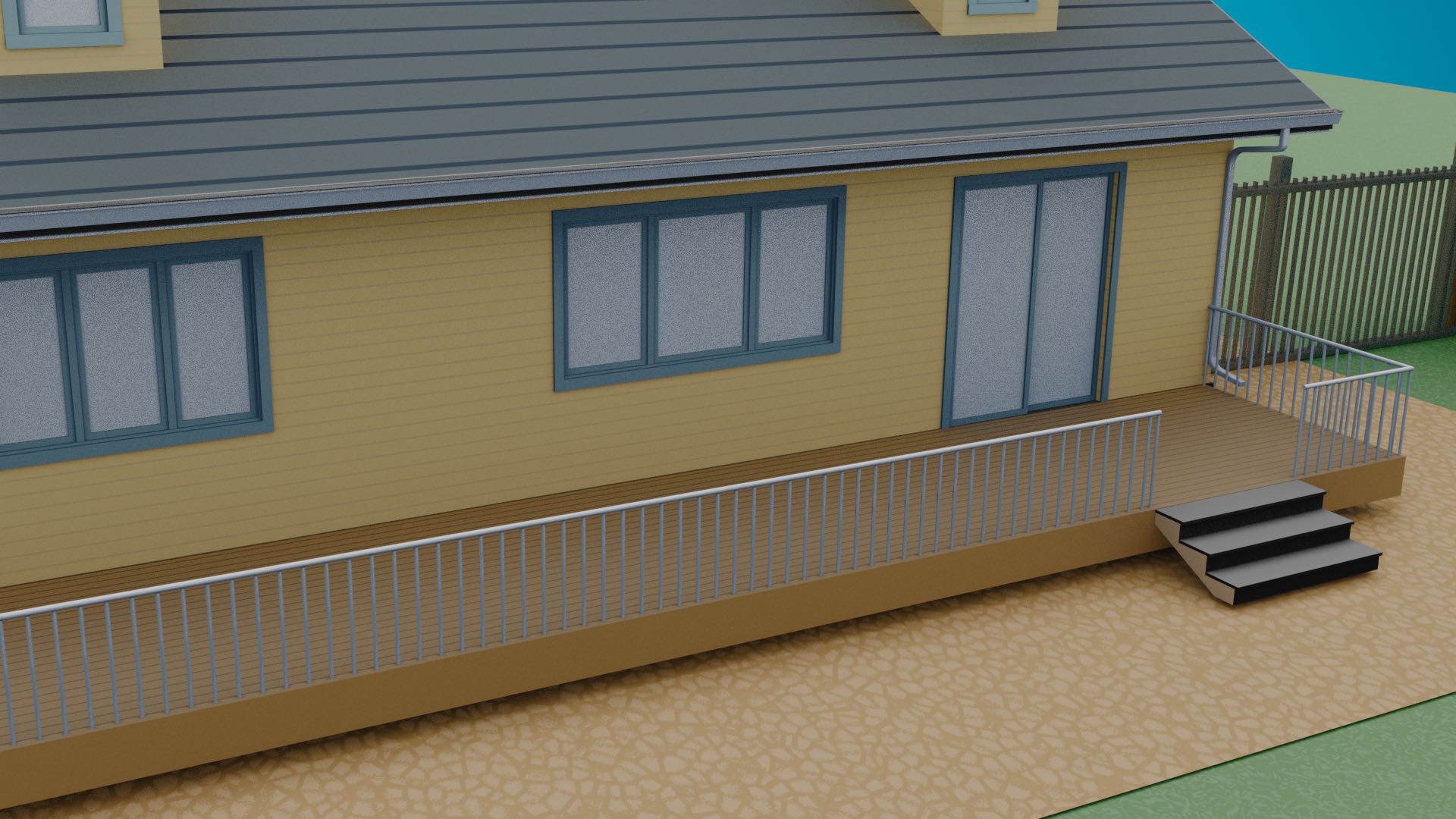

- Attached deck – horizontal surface area, rails, and under-the-deck footprint

- Near-home landscaping – the immediate five-foot perimeter around the home and attached deck (including mulch and fencing)

Cost estimates for individual building materials were provided through RSMeans, a national database of construction costs for residential, commercial, and industrial construction. Cost estimates included building material, labor, equipment, and contractor overhead costs such as transportation and storage fees.

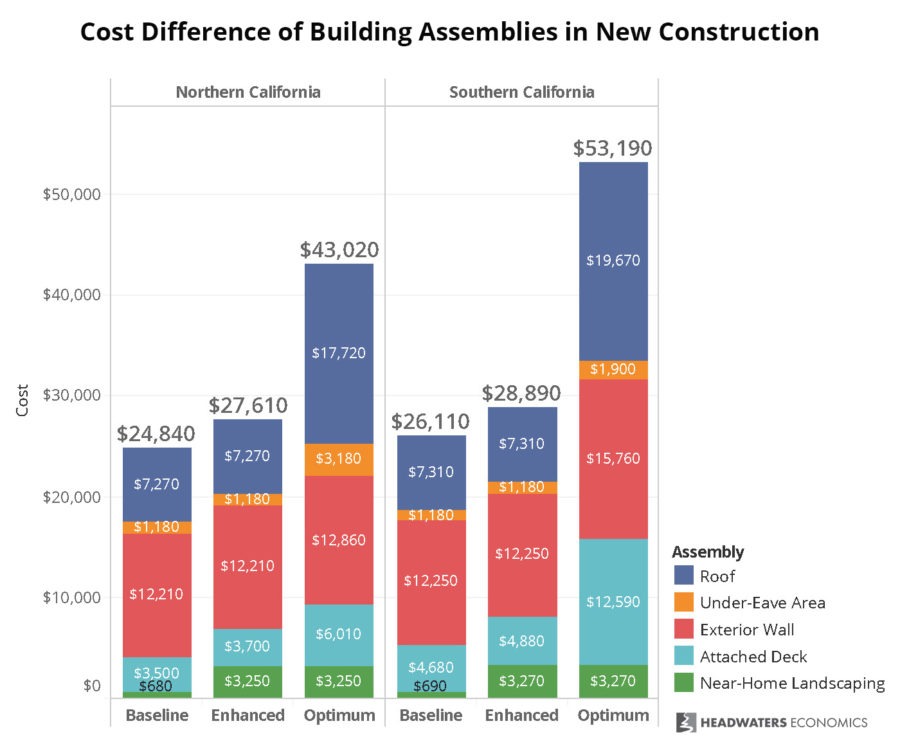

In northern and southern California, building an Enhanced wildfire-resistant home increased construction costs by approximately $2,800 over the Baseline home. Constructing a home to Optimum wildfire resistance increased overall costs by $18,200 in northern California and by $27,100 in southern California.

Although the Optimum home was more expensive to build, it is likely that the increased costs will return greater long-term benefits in energy efficiency and durability. The roof, exterior walls, and near-home landscaping added the largest proportional increases to building costs. Each of the five components is described in more detail below.

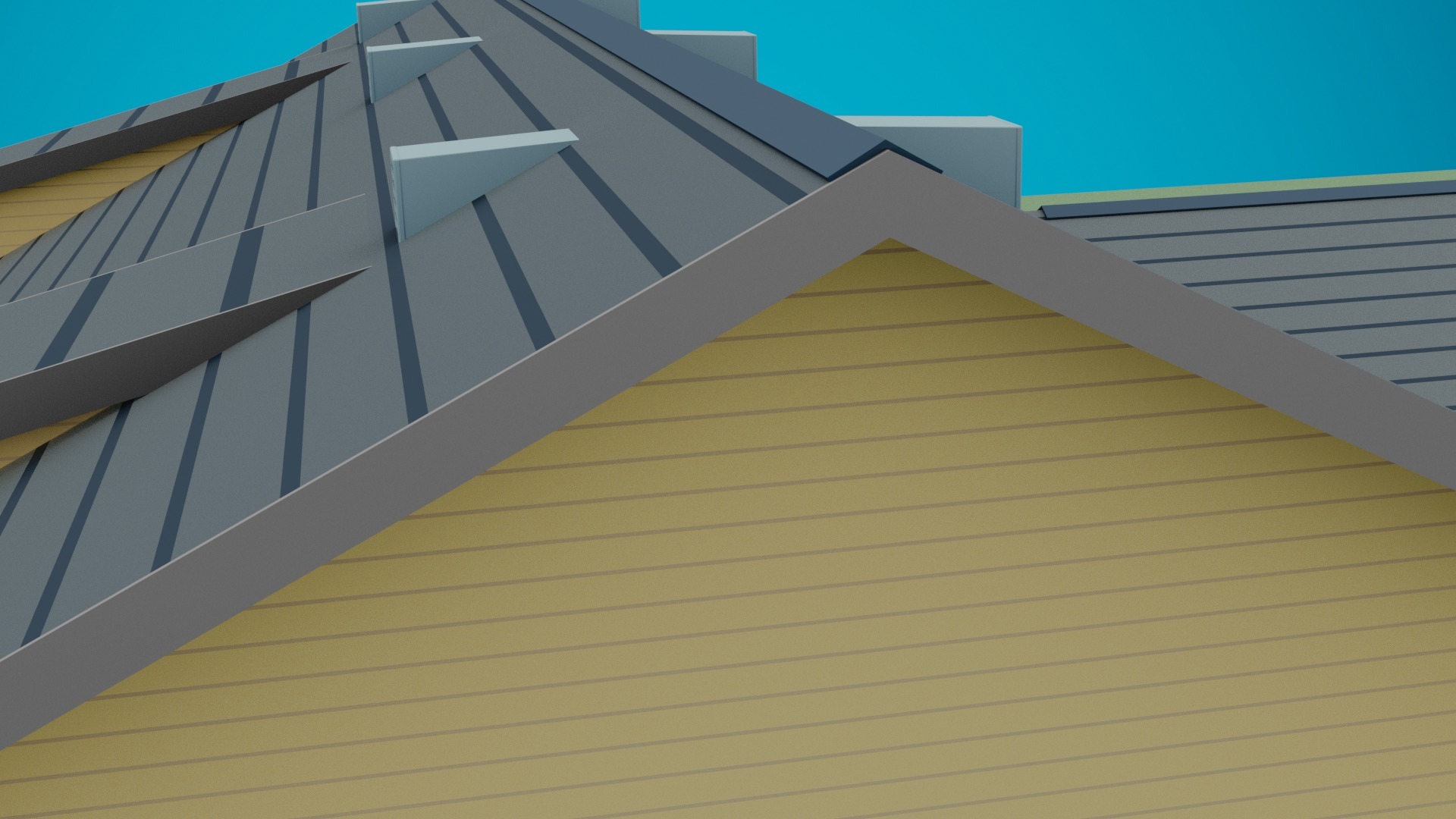

Roof

Roofs are highly vulnerable to ignition because of their relatively large horizontal surface area. Many Class A (wildfire-resistant) roof covering options are available, such as asphalt fiberglass composition shingles. The roof edge—including gutters and roof-to-wall intersections where the roof covering meets other materials (e.g., siding used in dormers)—is particularly exposed to ember ignitions. These areas must be properly protected by adding additional flashing at roof-to-wall locations.

For the Optimum home in northern California, a standing seam steel roof was selected for wildfire resistance instead of Class A asphalt composition shingles that were on the Baseline and Enhanced homes. Additional optimal wildfire-resistant measures to the roof included selecting a fire-resistant underlayment underneath the roof covering and using a noncombustible roofing edge (including fiber-cement fascia, metal gutters, metal gutter guards, and a metal drip edge).

In southern California, the Optimum wildfire-resistant home featured clay barrel-style tiles that were more expensive than the asphalt composition shingle roof used in the Baseline home. The barrel tile roof covering included noncombustible end-caps and an underlying mineral-surface roll roofing material. For the roof edge of the Optimum home in the south, metal drip edge, metal gutters, and metal gutter guards were selected as opposed to using a less expensive vinyl gutter system.

Under-Eave Area

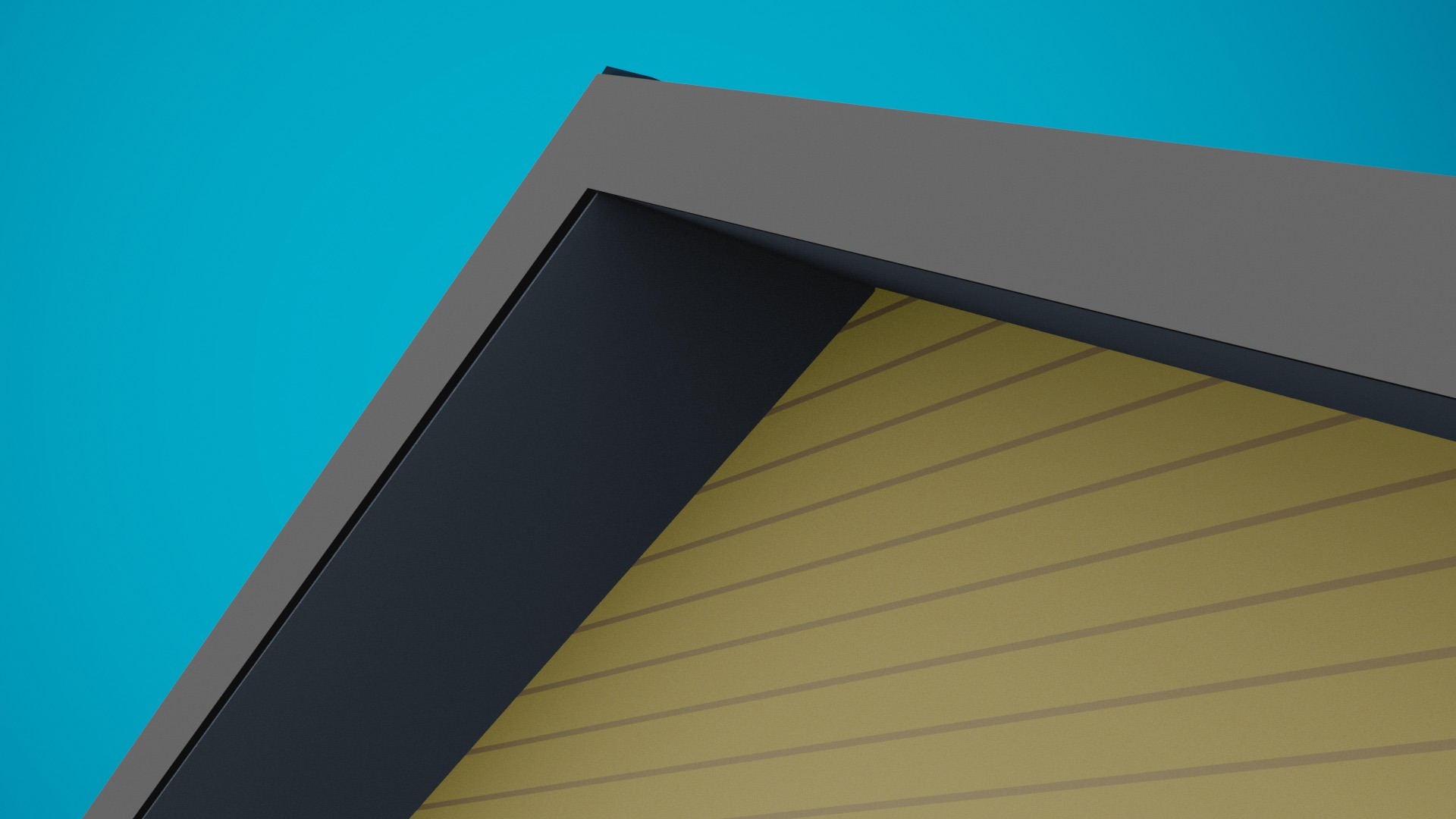

Eaves play an important role for building design but they also create vulnerabilities and pathways for the building to ignite. Embers can accumulate in gaps between blocking and rafters in open-eave construction. Should flames reach the under-eave area, open eaves can also trap heat. Once the under-eave area ignites, fire will spread laterally more quickly.

Vents in the under-eave area allow air to enter the attic space. During a wildfire, vent openings can also allow wind-blown embers into the attic space. If combustible materials in the attic ignite, the house can burn from the inside out. However, vents have recently been designed to resist flames and embers.

For the Optimum wildfire-resistant home in northern California, an enclosed (soffited) eave design using a fiber-cement material and flame- and ember-resistant strip vents were used rather than the open-eave design of the Baseline and Enhanced homes. For the Optimum wildfire-resistant home in southern California, an enclosed soffit covering using a three-coat stucco application and flame- and ember-resistant strip vents was used rather than the less-expensive open-eave design of the Baseline and Enhanced homes.

Exterior Walls

Exterior walls can be vulnerable if exposed to embers, flames, or prolonged exposure to radiant heat from burning items close to the home. Flames can spread vertically and laterally to other wall components such as windows, doors, and the under-eave area. Siding extending close to the ground can be vulnerable to ignition by embers accumulating at the base of the wall.

The Optimum home in northern California used fiber-cement siding, fiber-cement trim, and a galvanized metal dryer vent. These wildfire-resistant building materials cost more than the wood composite siding, wood composite trim, and vinyl dryer vent selected for the Baseline and Enhanced homes. By contrast, metal pedestrian and garage doors in the Optimum home were less expensive than the wood pedestrian and garage doors used in the Baseline and Enhanced homes.

In southern California, exterior walls of the Optimum home were constructed with a more expensive three-coat stucco rather than a wood composite siding product, and a more expensive, approved, flame- and ember-resistant vent was used rather than a plastic louvered vent. However, pedestrian and garage doors made with metal were less expensive than wooden pedestrian and garage doors used in the Baseline and Enhanced homes.

Attached Deck

A deck can cover a large horizontal surface area and is vulnerable to embers and under-deck flames. A burning deck can also expose the side of the house to heat and flames. The deck’s walking surface and structural support, as well as what is stored on or below the deck, are therefore important considerations. Enclosing the under-deck area can minimize the accumulation of vegetative debris, vegetation, and other combustible materials.

For the Baseline and Enhanced homes in northern California, a deck made with redwood decking boards, rails, and pressure-treated lumber for the structural support system was used. The Enhanced home additionally enclosed the under-deck area with 1/8-inch metal mesh screening. For the Optimum home, a metal railing and plastic-capped composite decking boards were used, and foil-faced bitumen tape was applied on the top of the pressure-treated lumber in the structural support system. In addition, a metal deck board was used at the deck-to-wall junction to create a noncombustible area next to the home.

For the southern California home, the Baseline and Enhanced decks were made with plastic composite (wood-grain-textured) non-capped decking material as opposed to the Optimum deck made with metal deck boards and a steel structural support system. The Enhanced home also enclosed the under-deck area with 1/8-inch mesh screening. In northern and southern California, the enclosed Enhanced home deck was slightly more expensive than the Baseline deck, and the Optimum deck was the most expensive and most wildfire-resistant option.

Near-Home Landscaping

Ignition of near-home combustible materials—such as fences, mulch, plants, vegetative debris, and other combustible materials—brings flames to the home. Reducing the availability of fuels within five feet of the home is an important mitigation strategy.

In this study, typical bark mulch and wooden fencing were assumed for the Baseline homes in northern and southern California. For the Enhanced and Optimum wildfire-resistant homes in both regions, the bark mulch was replaced with more expensive pea gravel on top of landscape fabric. The privacy fence was six feet high and made with galvanized metal chain links. It should be noted that while noncombustible mulch may be more expensive than combustible mulch, it is more durable and has a longer lifespan and therefore may save money over the long term. Wildfire-resistant upgrades in the Enhanced and Optimum homes cost somewhat more than the Baseline home.

Investing in Wildfire Resistance is Worth the Cost

Despite the added costs, investing in wildfire-resistant homes and neighborhoods increases overall community resilience for generations to come.

Research findings suggest that the cost of constructing a home with enhanced wildfire resistance—including an enclosed under-deck area and noncombustible zone from zero to five feet from the home— is not significantly higher than the cost of constructing a Baseline home compliant with Chapter 7A. Constructing a home to optimal wildfire resistance will increase overall costs by $18,200 to $27,100 but will return greater long-term benefits in energy efficiency and durability. Wildfire-resistant construction adds approximately 2-13% to the entire cost of a new home. (Baseline/ Enhanced building materials add 2-8%; Optimum building materials add 4-13%).

Chapter 7A has been reviewed and modified every three years since it was fully adopted in 2008. As it evolves, Chapter 7A in California’s building code can still be improved by adding provisions to reduce the vulnerability of homes to ignition from a threatening wildfire. The combination of better planning of housing developments, fuels reduction on nearby wildlands, management of vegetation and other combustible materials on the property, and construction of a home with wildfire-resistant building materials and design features can reduce the vulnerability of the built environment. With ever-increasing losses, damages, and risks, we cannot afford to wait.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Stephen L. Quarles and Daniel Gorham coauthored this report. This research was produced in partnership with the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety.