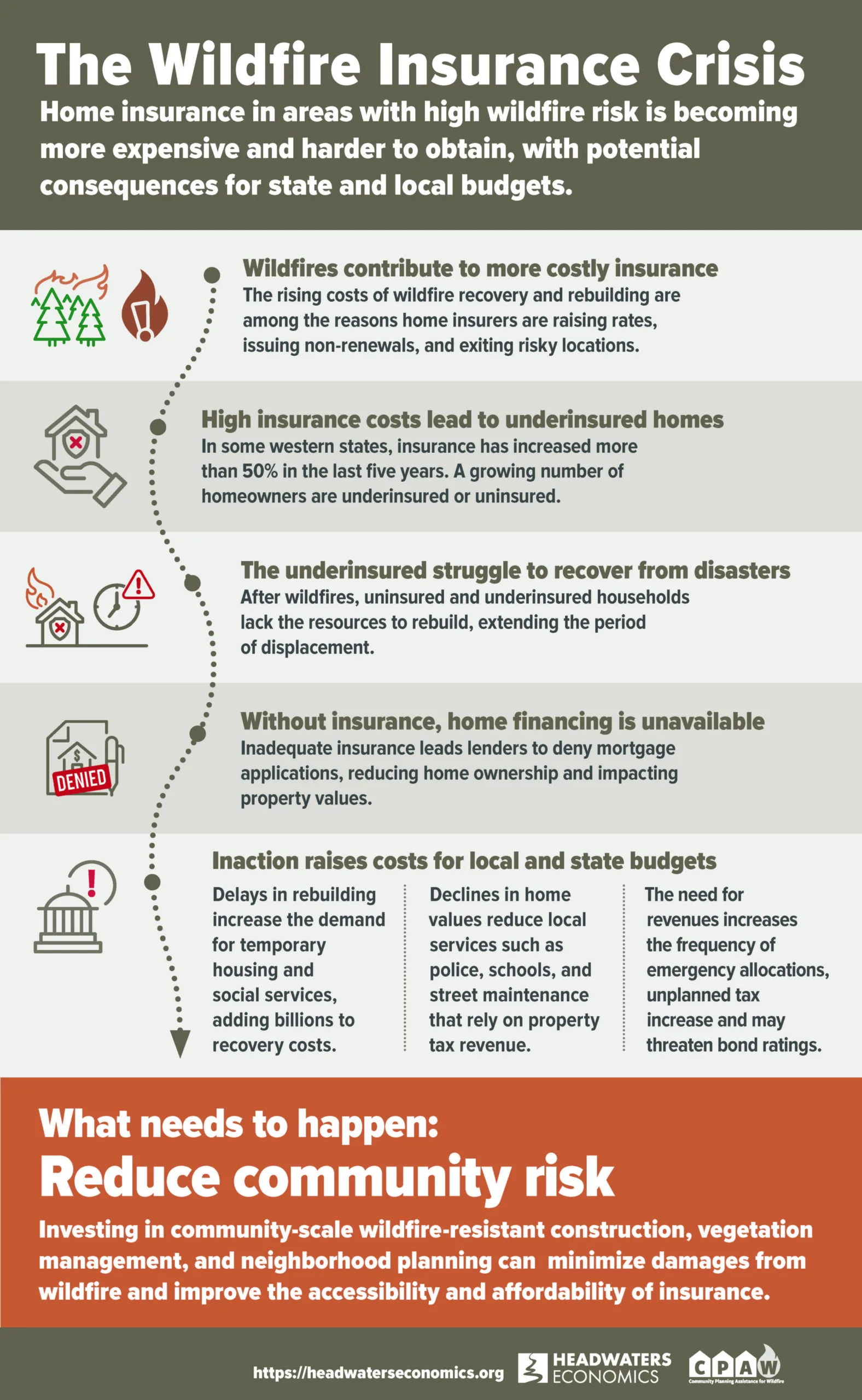

California’s catastrophic wildfires have underlined a home insurance crisis that is sweeping across wildfire-prone states. Rising premiums and policy non-renewals are being reported across the West, a result of changes in the insurance market driven by a suite of converging factors. Complex state regulations and dramatic increases in damage to homes and communities from wildfires in recent decades, paired with the rising costs of hurricanes, floods, and other natural disasters, are prompting insurers to raise rates and leave risky locations.

If these trends continue, the lack of available and affordable homeowners insurance will threaten housing markets and the ability of state and local governments to serve residents. The ripple effects would impact millions of people as unaffordable home insurance drives down local property values, increases vacancy rates, reduces tax revenues, and threatens budgets for crucial public services. Solutions to the insurance crisis must start with reducing community risk.

Wildfires now threaten the availability and affordability of insurance

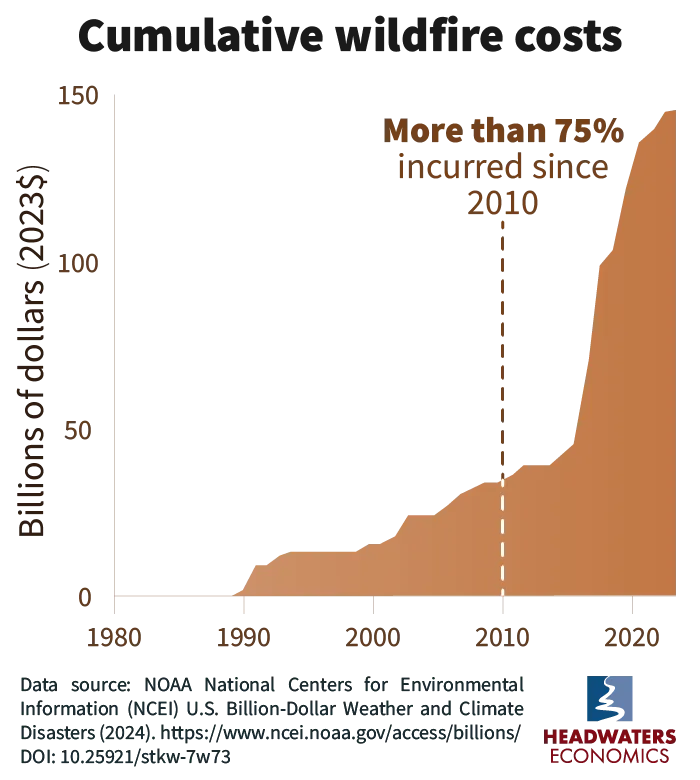

Home insurance rates rose by an average of 13% from 2020 to 2023 across the United States due to a variety of factors including state regulations and the costs of climate-driven disasters that are now occurring at a scale large enough to have a direct impact on the overall risk transfer market. In the last 30 years, the share of insured losses from wildfires has doubled as a proportion of total catastrophe claims. Today, wildfires are the fastest-growing source of hazard-related damages in the United States. With nine out of the 10 most expensive wildfires occurring since 2017, the costs for recovery and rebuilding are quickly outpacing what insurers say they can afford to pay.

To cover financial losses, some insurance companies are raising rates. For example, in California, New Mexico, Colorado, Oregon, Montana, and Washington, rising insurance premiums have drawn the attention of legislators. In 2023, Colorado’s Department of Regulatory Agencies reported insurance premiums increasing by more than 51% from 2019 to 2022. In California, major insurance companies like State Farm, AIG, and Allstate stopped issuing new home insurance policies. These trends are expected to continue, exacerbated by the increased severity of disasters, high construction costs, complex state regulations, and other economic factors.

Homeowners living in areas of high wildfire risk are already confronting this new financial burden. Among those most impacted are homeowners with mortgages, since insurance is required by lenders seeking to protect their investments. Nationally, almost two-thirds (62%) of housing units have a mortgage. Only people who own their homes outright or can afford to buy a home with cash are able to forego home insurance coverage. For everyone else living in areas with high wildfire risk, the cost of mandatory insurance is increasing at a pace that may threaten the viability of home ownership.

These financial pressures mean that some homeowners will face the prospect of foreclosure or a need to sell their homes, uprooting their families and jobs in the process. At a time when housing costs are already taking a higher share of incomes than ever, this scenario would intensify many of the struggles communities already face.

Financial pressures may also require insurers to separate or drop wildfire entirely from coverage plans. Homeowners could be required to purchase costly stand-alone wildfire insurance in addition to their traditional homeowners insurance policy, known as a difference in conditions policy. When homeowners can’t afford wildfire coverage, they will join the growing ranks of the uninsured. As a result, rebuilding and recovery after a wildfire would likely lag and reliance on scarce forms of government assistance would increase.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Inadequate insurance coverage will impact state and local government budgets and services

In any of the scenarios described above, a growing insurability gap has profound implications for the costs facing local and state governments.

Recent wildfires in Colorado and Hawaii are instructive. Following major wildfires, those states saw uninsured and underinsured households struggle to recover, increasing demands for temporary housing and social services. For example, an estimated 92% of the roughly 1,000 homes destroyed in Superior, Colorado’s 2021 Marshall Fire were underinsured. The extent of underinsurance created widespread delays in home repairs and extended the period of evacuation for more than 30,000 residents. The fire caused more than $2 billion in damages, with millions in recovery funds coming from federal, state, and local budgets. The town of Superior was forced to seek an increase in local sales taxes to cover fire costs and replace revenue losses stemming from businesses closing and residents leaving after the fire.

The August 2023 wildfire in Lahaina, Hawaii, was the deadliest U.S. wildfire in a century, killing 102 people and displacing 12,000. Less than a year after the disaster the state legislature allocated $1 billion in recovery funds for emergency housing, rental assistance, and victims relief. Independently, Maui County has also been forced to prioritize recovery efforts in its budget, despite expecting a decline in tax revenues directly related to the fire.

As these trends — rising wildfire risk and increasing challenges with insurance affordability and accessibility— continue, even communities that have not experienced a wildfire will start to see declines in property values and the public services such as police, schools, and street maintenance that rely on revenue from property taxes. The cascading effects start with increasing wildfire risks that eventually make insurance and housing less attainable, especially for a community’s low- to moderate-income households. When home buyers leave the market, it becomes difficult to sell homes without price reductions. Lower property values, higher rates of vacancy due to unsold homes, and lower tax revenues result. If home values fail to adjust, communities could struggle to provide workforce housing and public services for residents facing more unaffordable mortgages.

These trends may also threaten municipal bond ratings that can be adversely impacted by dropping revenue pledges generated by taxes and by climate risk. Reduced bond ratings jeopardize the ability of a community to finance ongoing basic services, infrastructure repairs, and capital improvements.

Each of these paths increases pressure on government spending and strains state and local budgets, pointing to the need for solutions that keep insurance accessible and affordable.

Solutions to the insurance crisis must start with reducing community risk

Since the insurance market is regulated at the state level, local governments ultimately have very little influence over decisions about how insurance is priced and managed. Still, local and state governments do have significant authority over building practices — including what materials are allowed for construction and how the area immediately surrounding the home is managed — that can greatly reduce the risk of wildfire damage to homes and property.

To keep insurance available and affordable, reducing the risk to homes and property before a wildfire disaster occurs is critical. For community leaders, this means requiring community-scale wildfire mitigation activities, and then investing the financial and technical resources to support those actions. Piecemeal requirements by insurance providers and voluntary measures to individual parcels will fall short of reducing overall community wildfire risk. Rather, the science of home-ignition shows that in addition to structural mitigation, neighborhood-level risk reduction is critical. This includes using wildfire-resistant building materials, maintaining a non-combustible zone around structures, and reducing fuels between homes. One homeowner can voluntarily mitigate risk, but their exposure remains high if their neighbors have not also mitigated for wildfire.

Local land use policies will have to require homes and properties to be built or retrofitted with wildfire in mind. Insurers will have to play a role in defining what wildfire-specific building and landscaping codes are needed to ensure homes have wildfire-resistant roofs, siding, windows, and more. Research shows these wildfire ignition-resistant materials are widely available and do not cost substantially more than traditional building materials. These actions will have to be coupled with development policies that encourage construction in appropriate areas and that require adequate infrastructure such as roads wide enough for evacuation and water supplies that meet fire response needs.

Community leaders already are identifying best practices that help them craft local regulations to protect against the loss of homes and businesses to wildfires. To boost their efforts, a federally administered Community Wildfire Risk Reduction Program should be formed to guide and support mitigation measures needed for homes, neighborhoods, and infrastructure. Such a program was recently recommended by the Congressionally established Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission. By proactively investing in risk reduction for homes and communities, the built environment will be better prepared before a wildfire disaster, and therefore easier to insure.

Finally, risk-reduction strategies must be coordinated alongside the insurance industry. Insurers will have to define what mitigation actions are required and at what scale for insurability to continue, and they must clearly communicate these standards to homeowners.

Policy innovations may increase access to insurance

In addition to reducing the risk of damages from wildfire, state and local governments may also have opportunities to expand available insurance options. Each approach has different possibilities and limitations. Among the ideas currently in play are:

Community-based catastrophe insurance: Community-based catastrophe insurance (CBCI) is a public-private model in which a government agency or nonprofit organization coordinates group insurance for multiple properties in the community. If arranged by local government, premiums can be assessed as a fee alongside property taxes. In some cases, rates could be discounted if certain mitigations are taken at the property scale, thus incentivizing wildfire risk-reduction activities.

Subsidies for the disadvantaged: Homeowners with low to moderate incomes, homeowners of color, and homeowners living in rural areas are more likely to be underinsured. State or local authorities could create income-based subsidies to reduce the financial risk these households are facing. Means-tested government subsidies to the most disadvantaged households could make insurance more affordable and attainable, while maintaining incentives for other policyholders.

Insurance certification programs: In these programs, households that have completed a list of mitigation measures can receive third-party certification. Insurers could then continue providing coverage for those who earned that certification. Mitigation measures would have to be maintained for certification to be renewed on an ongoing basis. Examples where this has been tried include Boulder County, Colorado’s Wildfire Partners Program, California’s Safer from Wildfire program, and the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS)’s Wildfire Prepared Home. These programs can help residents maintain their insurance coverage while simultaneously reducing overall wildfire risk and saving states and local governments millions of dollars in recovery costs and lost tax revenue.

What about state-run “insurance of last resort” plans?

State-run programs, commonly known as FAIR (Fair Access to Insurance Requirements) plans, are often set up as insurance of last resort for homeowners who cannot find private insurance. While considered a short-term fix to the insurance crisis, FAIR plan enrollment has increased over the past decade. Questions about the efficacy and viability of state-run insurance plans focus on taxpayer fairness, impacts on state budgets, inadvertently incentivizing development in high-risk locations, and the potential for risk mitigation requirements.

The world is changing – how we protect our communities must also change

No single solution best addresses the growing dysfunction in the risk transfer market. It is likely that several years of research, policy experimentation and coordination with insurance providers will be required to determine which approaches yield the most widespread benefits.

Yet when it comes to protecting homes, many effective approaches are available today. Investing in community-scale wildfire-resistant construction, vegetation management, and neighborhood planning can limit damages from wildfire, and thus reduce the insurance claims that are driving up premiums. Wildfire-resistant homes can be built in ways that are not cost prohibitive, and often add benefits of energy efficiency and durability. Retrofitting existing homes to reduce their vulnerability can also be done affordably. By strategically reducing fuels in and around communities, managing vegetation on properties, and carefully planning development, we can reduce the vulnerability of the built environment that is at the root of the wildfire home insurance crisis.

Wildfire risks will continue to grow and threaten more homes as development in wildfire-prone areas continues. As the world evolves around us, insurers, homeowners, and governments alike must evolve as well to ensure a more resilient future for our communities.

Subscribe to our newsletter!