Missing the mark:

Effectiveness and funding in community wildfire risk reduction

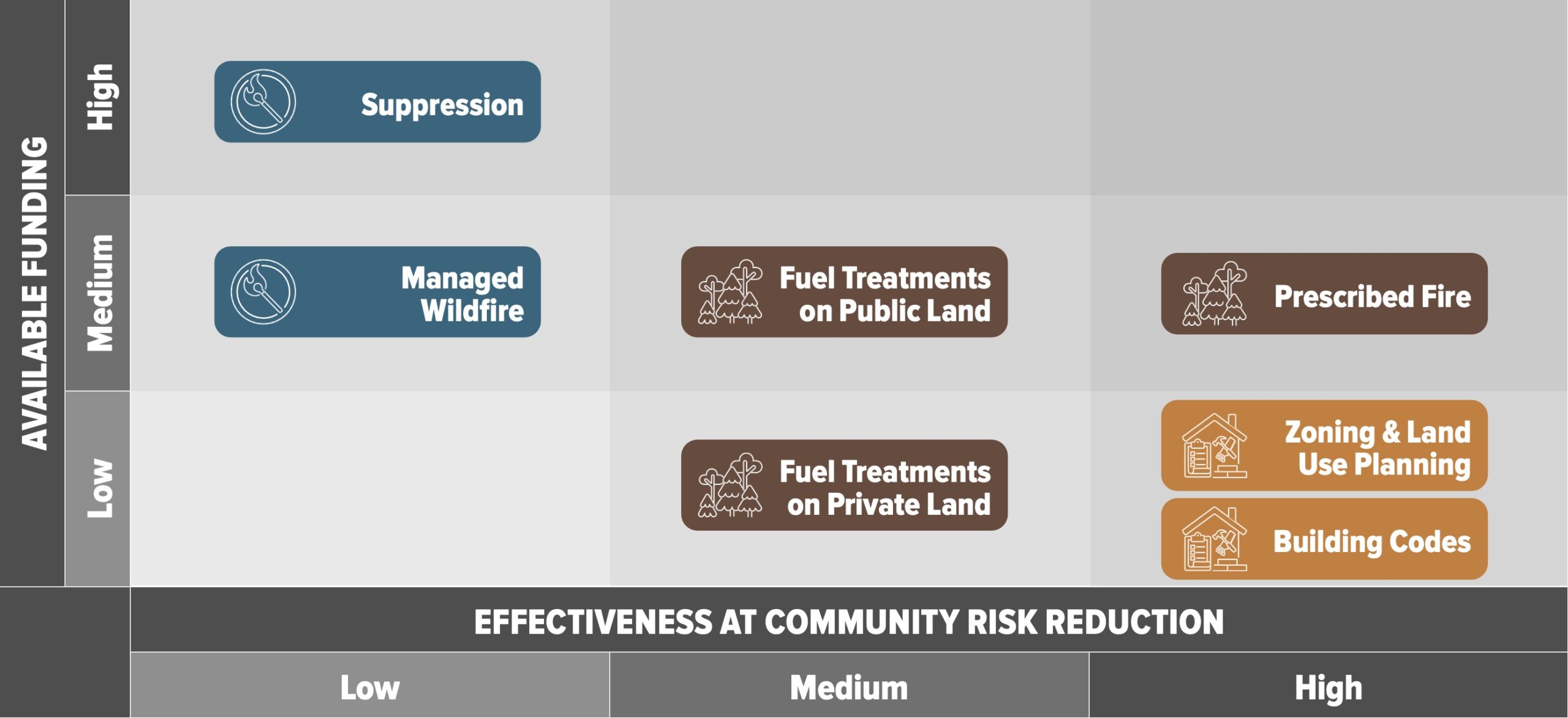

An analysis from Columbia Climate School and Headwaters Economics finds that the most effective strategies for reducing community wildfire risk—those that manage the built environment—tend to receive the least funding and policy support when compared to the suppression or fuel management strategies most deployed at the federal and state levels.

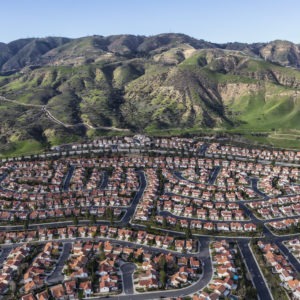

The analysis comes as more communities face increasing wildfire risk due to climate change, development encroaching on wildfire-prone areas, and decades of fire management policies that often make landscapes even more susceptible to large and intense fires. These trends have raised questions about what strategies can best protect homes and buildings, and how they can be implemented.

To answer those questions, researchers at Columbia Climate School and Headwaters Economics analyzed the entire spectrum of wildfire policy responses made by state and federal governments to identify which strategies are the most effective, and whether they are receiving adequate policy support and funding. The results are detailed in a report, Missing the Mark: Effectiveness and Funding in Community Wildfire Risk Reduction.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

The report’s conclusions are the consensus of 38 expert interviews the authors conducted with land managers, local officials, scientists, and firefighters. In addition to interviews, the authors surveyed hundreds of scholarly and technical papers, as well as congressional reports and budget documents.

Missing the Mark breaks out wildfire response strategies into three categories: managing fire, managing fuels, or managing the built environment. These categories mirror the goals of the National Wildland Fire Management Cohesive Strategy, a nationwide collaboration led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to manage wildfire more effectively across all landscapes.

Managing fire

Wildfire suppression efforts have been extraordinarily effective at putting out fires: More than 99% of fires are suppressed before they exceed one acre in size. Yet decades of suppression efforts have also short-circuited the essential role that fire can play in forests. The result is more intense, larger fires that threaten communities. The report concludes that policies aimed at managing fire receive the most funding and support, but that they are ultimately not adequately effective at reducing the wildfire risks faced by communities today.

Managing fuel

Managing fuels can preemptively reduce the amount of flammable material on a landscape in the hopes of controlling a future fire or reducing its intensity. Fuel management can include mechanical treatments and prescribed fires. These strategies receive billions in funding and were found to be effective tools for reducing wildfire risk in localized settings, especially near communities. But the rate of fuel treatments simply does not have measurable impacts relative to the scale of the wildfire problem in the West. Further, fuel management is often burdened by complex protocols on public lands and challenging public perceptions of risk.

Managing the built environment

Layered regulations at the community scale—like zoning, building codes, and retrofit programs—can help ensure homes in wildfire-prone areas are hardened against the embers and radiant heat of a wildfire. Missing the Mark concludes there is ample evidence that wildfire-resistant construction and applicable building codes are highly effective at reducing wildfire risks to communities, and that they are not prohibitively expensive to implement. They have also been shown to save millions in avoided expenses. At the same time, funding for those efforts has been elusive. Federal agencies provide little guidance and financial assistance to facilitate these approaches, and only a few states have implemented robust policies. As a result, community leaders and homeowners are left without the support, information, and encouragement they need to reduce the risk from wildfire.

Recommendations for federal and state policy

Turning attention to the built environment can likely substantially reduce wildfire risks faced by millions of people living in wildfire-prone areas. Missing the Mark offers some recommendations for federal and state policy:

- Congress should create and fund home-hardening programs. These efforts should complement and support existing programs for communities in agency budgets.

- Federal agencies should modify protocols regarding wildfire suppression to facilitate treating more acres with managed and prescribed fire, especially near at-risk communities, and prepare individuals and communities to be “Smoke Ready.”

- State governments should encourage mandatory building codes in wildfire-prone areas, and support market strategies for timber including development of biomass energy.

A new focus on the built environment should not be viewed as a substitute for suppression efforts, but it must become a part of coordinated efforts to keep communities safe. The tools and strategies are readily available, and by devoting more resources to the most effective approaches we can help communities be better prepared to live with increasing wildfire risk.

Acknowledgments

This report was a collaborative research effort by Headwaters Economics and Columbia Climate School. It was co-authored by Dr. Lisa Dale and Dr. Kimiko Barrett. The authors also wish to thank Allegra Reister for her research contributions.