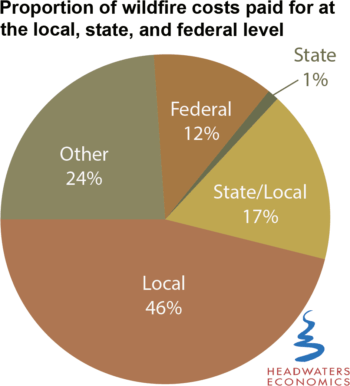

- Almost half of the full community costs of wildfire are paid for at the local level, including homeowners, businesses, and government agencies.

- Many of these costs are due to long-term damages to community and environmental services, such as landscape rehabilitation, lost business and tax revenues, and property and infrastructure repairs.

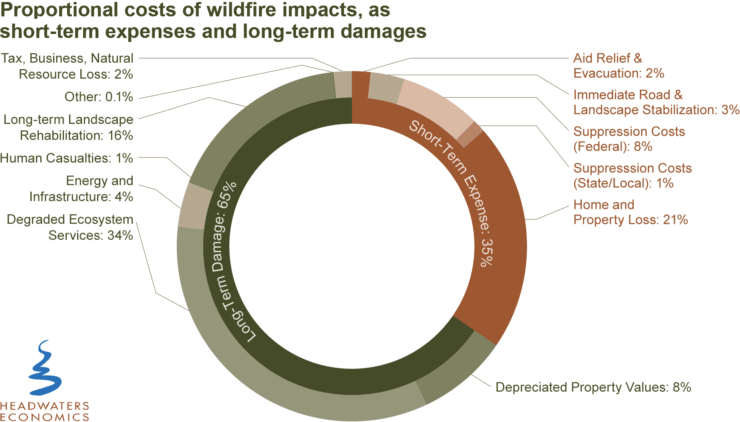

- By comparison, our analysis suggests suppression costs comprise around nine percent of total wildfire costs. The remaining costs include short-term expenses, or those costs occurring within the first six months—and long-term damages accruing during many months and years following a wildfire.

- Communities at risk to wildfires can reduce wildfire impacts and associated costs through land use planning.

Full Community Costs of Wildfire

Analysis of the literature suggests nearly half of the full community costs of wildfires are paid at the local community level by government agencies, non-governmental organizations, businesses, and homeowners. Almost all wildfire costs accrued at the local level are the result of long-term damages such as landscape rehabilitation, lost business and tax revenues, degraded ecosystem services, depreciated property values, and impacts to tourism and recreation.

The remaining wildfire costs are paid at the state and federal level, or are paid by a combination of local, state, and federal organizations. State and federal agencies are responsible for paying the bulk of suppression costs.

While substantial, suppression costs comprise only nine percent of total wildfire costs; additional short-term expenses and long-term damages account for 91 percent of total wildfire costs. Overall, short-term expenses such as relief aid, evacuation services, and home and property loss comprise around 35 percent of total wildfire costs. Related costs from long-term damages, which can take years to fully manifest, account for approximately 65 percent of total wildfire costs.

This report summarizes the accumulated impacts and associated costs of wildfires at the local, state, and federal level. Drawing from existing literature and five case studies—the Hayman (2002), Old, Grand Prix, and Padua Complex (2003), Schultz (2010), Rim (2013), and Loma fires (2016)—we categorize wildfire impacts into short-term expenses including suppression costs spent on firefighting, and long-term damages including costs that accrue in the months and years after a wildfire.

Wildfire costs greatly vary depending on factors within the built and unbuilt environment. Socioeconomic context, housing density, the duration and size of a wildfire, and other variables influence the overall cost of a wildfire. In general, upward trends in urban growth and development in areas at risk to wildfires suggest a parallel rise in total wildfire costs.

Additionally, climate change is influencing the frequency, intensity, and duration of wildfires and will likely exacerbate wildfire costs in the future. California’s wildfire season in 2017, for example, demonstrates the extent of devastation that can result when wildfires spread into dense housing developments and are fueled by dry and windy weather conditions. While early projections of the full costs of California’s historic wildfires are preliminary at the time of this writing, some estimates are into the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Planning with Consideration of Wildfire Risks

In the aftermath of a wildfire, local communities shoulder the responsibilities and costs of ongoing recovery. Homeowners, businesses, local organizations, and agencies can take years to financially rebound, and perhaps longer to heal emotionally and psychologically. Yet as more people continue to build in harm’s way and as wildfire trends rise, wildfire costs will increase.

Planning new communities and developments with consideration of wildfire risk is one way to accommodate growth while living alongside wildfires. Land use planning strategies can be integrated into the development process. For instance, the prudent placement and layout of roads, infrastructure, and services can reduce wildfire risks to homes and improve evacuation and response efforts. Similarly, requiring ignition-resistant building materials in the construction and design of homes in at-risk areas can reduce wildfire impacts.

To further reduce wildfire risks and improve community safety, land use planning strategies must supplement other mitigation measures such as vegetation treatment projects and forest management approaches. By realizing that local communities bear the brunt of wildfire costs, elected officials and decisionmakers can take steps now in the planning and design of their communities to prevent devastating wildfire impacts in the future.

Conclusion

Wildfires can have significant social, economic, and environmental implications that extend well beyond initial suppression costs. Identifying the broad spectrum of these outcomes, and who pays for them, illustrates the full reach of wildfire devastation.

Our analysis aligns with existing literature and suggests suppression costs comprise around nine percent of total wildfire costs. The remaining costs include short-term expenses, or those costs occurring within the first six months—and long-term damages accruing during many months and years following a wildfire.

Almost half of all wildfire costs are paid for at the local level, including homeowners, businesses, and government agencies. Many local wildfire costs are due to long-term damages to community and environmental services, such as landscape rehabilitation, lost business and tax revenues, and property and infrastructure repairs.

Communities at risk to wildfires can reduce wildfire impacts and associated costs through land use planning. Land use planning is complementary to other wildfire mitigation strategies to reduce wildfire risks and costs. Examples of land use planning tools to reduce wildfire risk include regulations requiring homes located in high-risk areas to be constructed using fire-resistant building materials or incentives for directing new development away from wildfire-prone areas.