Federal wildfire policy that emphasizes suppression—a legacy of early-1900s forest management—has resulted in a paradox: accumulated fuels and larger, more severe wildfires. For communities to truly become fire-adapted, suppression efforts must be complemented with other preventative and mitigation measures.

Overview

Enormous amounts of resources are expended in containing and extinguishing a wildfire. While widely successful, wildfire suppression is dangerous, costly, and will become more difficult as wildfires increase in size, severity, and frequency.

Wildfire suppression is deeply wedded to early forest management and policy. In the wake of a series of catastrophic wildfires in the early 1900s, the federal government pledged to protect communities and natural resources from the damages of wildfires.

The federal government’s commitment to minimize the threat of wildfires has resulted in the near eradication of wildfires from the landscape for decades. However, successful wildfire suppression has resulted in accumulated fuels that lead to larger and more severe wildfires in the long-term—what is known today as the “wildfire paradox.”

The government’s predominant focus on active wildfire suppression disregards more proactive wildfire responses such as community planning and preparedness. Public expectations and policy goals must recognize and adapt to the inevitability of large wildfires.

This post is based on an article originally published in the Idaho Law Review, Volume 55(1). Also read this companion post about land use planning to reduce wildfire risk.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

The Great Fires (1870s-1910s)

Large and devastating wildfires influenced early European settlement of America. As more people migrated west, vast areas of land were burned and cleared for development. Towns and cities constructed entirely of wood were densely populated and highly vulnerable to wildfires.

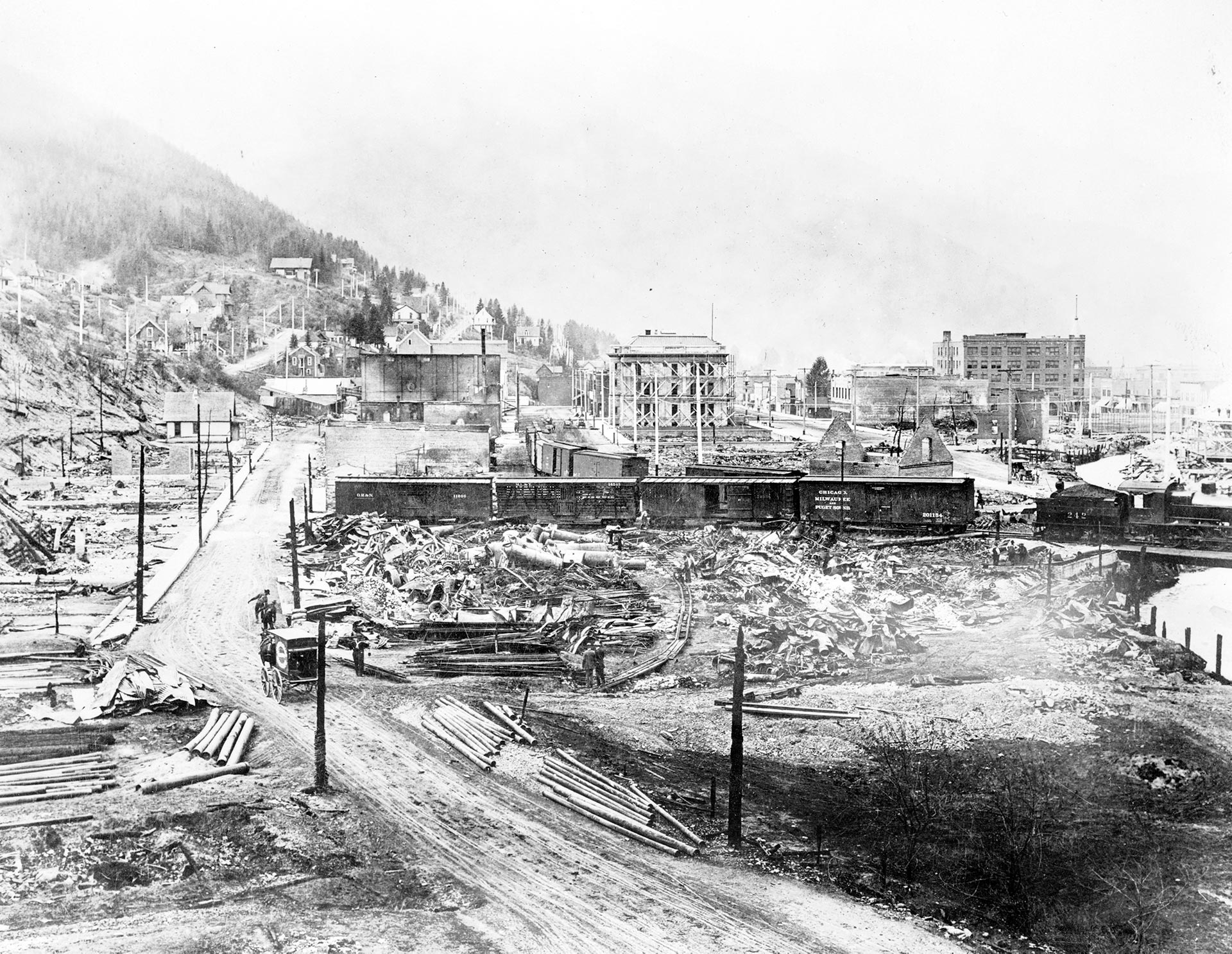

The Chicago Fire in 1871, for example, destroyed 17,000 structures, killed 300 people, and left more than 100,000 people homeless. On the same day the Chicago Fire started, the Peshtigo Fire in Wisconsin burned 1.2 million acres and killed more than 1,500 people and remains America’s most tragic wildfire in history.

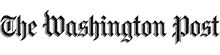

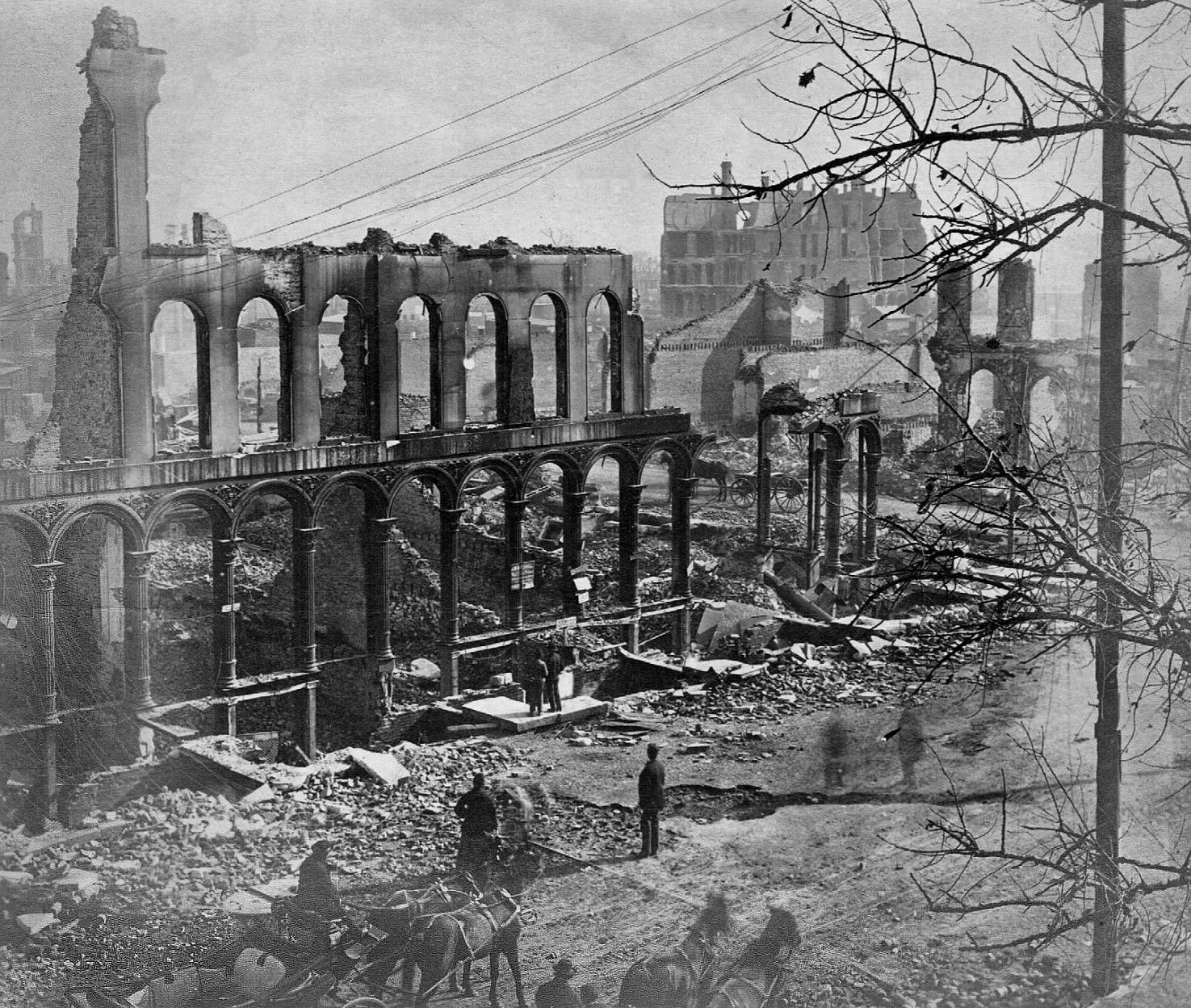

In 1910, a series of small wildfires ignited in Montana, Idaho, and Washington ultimately merged into one large firestorm known as the Great Blowup, or Great Fires. Sweeping through the northern Rockies and fueled by especially dry and windy conditions, the Great Fires destroyed several towns in its path, including much of Wallace, Idaho. Within 36 hours, 86 people were dead, more than 3 million acres were burned, and the nation’s entire fire protection front was overwhelmed. Smoke from the wildfires was reportedly seen as far away as Boston to the east and 500 miles west into the Pacific Ocean.

Aftermath of the Great Fires (1910s-1920s)

The wildfires of 1910 influenced early forest policy and management in two significant ways. First, the fires reaffirmed the role of the government’s administrative involvement in the West while also testing the capabilities of the country’s firefighting defenses. The Great Fires became a defining moment for the Forest Service, which at that time was a fledging agency. The three Forest Service chiefs following the first Forest Service chief, Gifford Pinchot, were all former firefighters who were personally involved with the Great Fires. Well acquainted with the potential devastation wrought by uncontrolled wildfires, the chiefs and the agency they led made it their primary mission to extinguish all wildfires upon initial attack.

Secondly, the wildfires of 1910 imposed a heavy toll on firefighters and the agency budget that supported them. Fighting the wildfires required 10,000 men, most of the Army Reserves based in the Northwest, and a substantial amount of resources. When the wildfires were finally extinguished in late fall, the Forest Service had accrued a $1.1 million deficit and an estimated $25 million in lost timber revenue. The following year, Congress substantially increased Forest Service appropriations, and with public expectations high, directed the agency to prioritize wildfire prevention above all else.

Taming the Wildfire Problem (1930s)

During the 1930s, the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided the labor and means to implement the government’s agenda and “no burn” policy. The CCC was broadly deployed to construct the nation’s wildfire protection infrastructure, including trails, roads, communication lines, fuel breaks, and observation posts.

The CCC was also organized into firefighting crews and was important in monitoring wildfires igniting in the backcountry. With much of America’s forests now under surveillance, wildfire suppression soon overshadowed all other land management options.

Popular opinion regarding extinguishing all wildfires was solidified by the Tillamook Fire in 1933. Burning nearly 300,000 acres, the Tillamook Fire was fueled by particularly warm temperatures and windy conditions. At the time, it was the largest wildfire in the Northwest, and its rapid spread across the Oregon forest renewed pressure on the Forest Service to control wildfires as soon as they started. In response, the agency adopted a “10 a.m. policy” which sought to extinguish all wildfires by the following morning.

The Wildfire Campaign (1940s-1950s)

Wildfire prevention came to the forefront of popular culture in 1944 when the Forest Service unveiled Smokey Bear . One of the most successful public awareness campaigns ever, Smokey Bear was more recognizable than the president of the United States at the time. Following World War II, wildfire suppression efforts were heavily bolstered by the addition of surplus equipment from the war. Applying military combat tactics on wildfires, wildfire suppression became mechanized with airplanes, trucks, and tanks. By the late 1940s, America had some of the most well-equipped and proficient wildfire protection crews in the world.

Preliminary Wildfire Policy Reform: 1960s-1980s

In the late 1960s a gradual paradigm shift emerged regarding the role of wildfire on the landscape. A growing body of literature demonstrated the ecological benefits of wildfire in revitalizing vegetation, reducing fuels, and preventing high-intensity wildfires. In 1971, the 10 a.m. policy was slightly amended to containing all wildfires to 10 acres or less, and shortly thereafter, the policy was dismissed entirely. In some national parks, such as Sequoia and Yosemite national parks in California, natural wildfires were allowed to burn under certain conditions. Under the auspices of “Natural Fire Management Programs,” a let-it-burn policy was applied to natural wildfires occurring in the wilderness during specific times of the year.

The prescribed natural fire approach soon came under heavy public and political scrutiny. In 1978, the Ouzel Fire was allowed to burn in Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado for more than a month before it came dangerously close to a neighboring community. A review of the event later concluded the natural burn fire plan was not properly implemented and was lacking important ecological knowledge. As a result, prescribed natural burning was temporarily suspended in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Ten years after the Ouzel Fire, the Yellowstone Fires of 1988 ushered in a new era of wildfire awareness. That summer, 10 individual fires—both natural and human-ignited—burned nearly 1.4 million acres in and around Yellowstone National Park, primarily in Wyoming.

As a result, the secretaries of Agriculture and Interior convened a policy review team to evaluate wilderness wildfire policies. Although the review team reaffirmed the value of wildfire, they encouraged more accountability and interagency cooperation in wildfire response. Pending the approval of new wildfire plans, all prescribed natural burning was suspended in national parks and wilderness areas.

The Wildland-Urban Interface: 1990s

In 1994, Colorado’s South Canyon Fire triggered another joint review of wildfire policy. Although suppression action was taken two days after ignition, the wildfire eventually killed 14 firefighters. In response to the South Canyon incident, Congress launched a comprehensive review and update of federal wildland fire policy, the first in decades.

“[A]gencies and the public must change their expectation that all wildfires can be controlled or suppressed. No organization, technology, or equipment can provide absolute protection when unusual fuel build-ups, extreme weather conditions, multiple ignitions, and extreme fire behavior come together to form a catastrophic event.”

Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy and Program Review, 1995

One year later, the Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy and Program Review recognized wildfire was part of a larger problem and considered the role humans were playing in influencing wildfire behavior. The report prioritized the protection of firefighters, public safety, resources, and community while also acknowledging there was a place for nature to take its course. Challenges related to previous years of wildfire suppression were integrated into a new understanding of landscape-level resource management and collaborative landowner decision-making.

The 1995 policy review was also one of the first widely circulated government documents to identify the challenges associated with wildfires in the wildland-urban interface (WUI). According to the review, the problem with wildfire response in the WUI involved mixed private and public land ownership as well as an increasing number of homes. Further, public perception of wildfire in the WUI was low despite the high values at risk. The review went on to identify several locally-based solutions including hazard mitigation and fuels reduction through zoning regulations, federal-state fire protection agreements, improved fire response apparatuses, and involving insurance companies in rating wildfire-prone properties. Recommendations from the 1995 policy review established the guiding principles and legislative framework for wildfire management over the next 20 years.

Addressing the Wildfire Problem: 2000-2010

Following the severe wildfire season of 2000, President Clinton directed the secretaries of Agriculture and Interior to develop an improved strategy to manage and reduce the impacts of wildland fires. The resulting report, entitled Managing the Impacts of Wildfire on Communities and the Environment: A Report to the President in Response to the Wildfires of 2000, was released in 2001 and was referred to as the National Fire Plan (NFP). Aligning with the 1995 policy review, the NFP focused on firefighter safety and ensuring sufficient future resources, forest rehabilitation, suppression, fuels reduction, and rural community assistance. At the same time the NFP was released, Congress passed the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act (PL 106-291), which directed the secretaries of Agriculture and Interior to coordinate with the Western Governors’ Association (WGA) on a national 10-Year Comprehensive Strategy for implementing the NFP. Both the NFP and the 10-Year Comprehensive Strategy recognized severe wildland fires and associated suppression costs would increase if alternative methods, such as fuels reduction projects, were not implemented.

In 2003 the NFP was augmented with the Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA) signed by President G. W. Bush. The HFRA sought to restore the ecological benefits of wildfires by establishing programs of aggressive thinning, prescribed burning, and replanting to create open conditions in forests. Despite protests from conservationists, the HFRA expedited the approval of proposed fuels reduction projects and stymied litigation by altering permissible activities regulated by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The HFRA was proclaimed to streamline the environmental review process by trimming down “bureaucratic red tape” as it widely granted fuels reduction projects on public lands.

Recognizing suppression costs were consistently depleting the Forest Service budget, Congress passed the Federal Land Assistance, Management and Enhancement (FLAME) Act in 2009. FLAME reconfigured the method for allocating the Forest Service’s wildfire budget to better reflect recent trends in wildfire costs. Until then, the allocation of the agency’s budget was based on an unpredictable system of a rolling 10-year average. Under this model, the Forest Service requested funds for its upcoming season based on the average wildfire costs for the previous 10 years. Under the new legislation, suppression funding would be calculated based on the data and methods from the previous year.

Increasing Wildfire Risks and Costs: 2010s

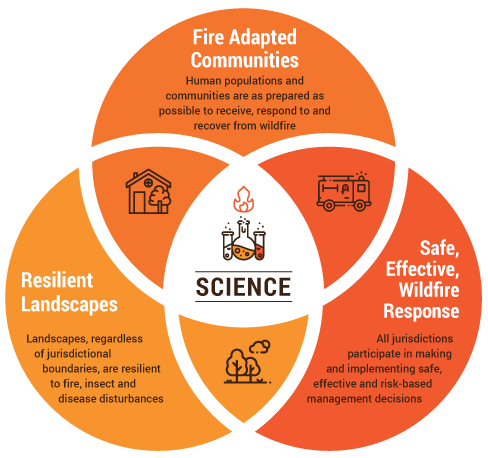

To guide the directives outlined in FLAME, a National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy (Cohesive Strategy) was developed. Released in 2014, the Cohesive Strategy took a holistic view of wildfire on the landscape with a mission to both safely extinguish wildfires when required while allowing others to burn when no homes, people, or values are threatened. Orienting the approach were the three themes of restoring resilient landscapes, creating fire-adapted communities, and safe, effective wildfire response. Coordinated by the Wildland Fire Leadership Council, recommendations from the Cohesive Strategy continue to inform federal wildfire policy.

At the time, the Cohesive Strategy was one of the most comprehensive efforts to address the seemingly insurmountable task of abating wildfire suppression costs while also protecting communities from escalating wildfire risks. By 2017, federal wildfire suppression appropriations were more than $2 billion a year—more than six times the average amount spent on suppression activities during the 1990s. At this rate, estimated wildfire suppression costs would consume nearly 70% of the Forest Service budget by 2021. Traditionally, a shortfall in the Forest Service budget required borrowing funds from other land management programs. During severe wildfire seasons, wildfire borrowing drained agency budgets and compromised important outdoor and recreational services such as watershed management, infrastructure repairs, and forest treatment projects.

To end the cycle of deficit spending and wildfire borrowing, a massive appropriations bill was passed in 2018—which was also the worst wildfire season in decades and saw the death of over 80 civilians from the Camp Fire in Paradise, California. Captured as a provision in the omnibus bill, the “wildfire fix” treats wildfires similar to other natural disasters and establishes a reserve fund to use during extreme wildfire seasons. Starting in 2020, a wildfire disaster fund of $2.25 billion was created and will be gradually increased over the following 10 years. When the Forest Service’s suppression costs exceed annual appropriations, based on FY2015 levels, funds can be withdrawn from the reserve budget rather than borrowing from nonfire programs. The spending bill also increases funding for fuels reduction projects, grants environmental review exemptions for projects meeting categorical exclusion, extends land stewardship programs, and initiates the process of wildfire risk mapping.

The 2018 wildfire fix was widely applauded by nongovernmental organizations, industries, and policymakers for stabilizing agency budgets and ending wildfire borrowing. While the new legislation provides the Forest Service with the financial flexibility to accommodate soaring suppression costs, it reaffirms the government’s prioritization of fire control and the protection of people and homes at any price.

From Federal Policy to Local Action

Continued reliability on wildfire suppression shifts responsibility for home protection from the individual homeowner and local jurisdictions to the federal government. Yet local communities bear the economic, environmental, and social costs of wildfire disasters, and some of the most essential mitigation actions need to be taken at the scale of individual communities and homes.

At the neighborhood and community scale, land use planning provides a suite of mitigation measures. Land use planning tools, such as regulations, zoning, and building codes can influence how, where, and under what conditions homes can be built in high wildfire hazard areas. Through the proactive lens of planning and anticipating wildfires, people and communities can learn to live with wildfire on the landscape.

By performing basic home mitigation measures, such as trimming trees, managing vegetation, safely storing flammable materials away from the home, and reducing other vulnerabilities within the home ignition zone (HIZ), a home’s chances of surviving a wildfire greatly increase. Constructing a home using wildfire-resistant building materials can also contribute to a home’s survivability during a wildfire.

Conclusion

Large and extreme wildfires are inevitable and efforts to extinguish them are costly, dangerous, and unrealistic. The federal government’s ongoing commitment to wildfire suppression is rooted in early 20th century policies that haven’t kept pace with current science and knowledge on wildfire behavior. If communities are to become truly fire-adapted, suppression efforts must be complemented with other preventative mitigation measures.

This post is based on an article originally published in the Idaho Law Review, Volume 55(1). Also read this companion post about land use planning to reduce wildfire risk.