On August 2, 2019, in western South Dakota, seven inches of rain fell in four hours. In the small town of Custer, a powerful flash flood tore down Washington Street, ravaging roads, bridges, and homes along French Creek. With almost no warning, residents were forced to evacuate. So were thousands of people visiting the Black Hills during Custer’s peak tourist season.

Local emergency managers sprang into action to ensure immediate safety, and the community rallied to assist families whose homes were flooded. After urgent needs were met and officials had assessed the hundreds of thousands of dollars in infrastructure damage, community members began to wonder: How could they make sure this never happens again?

After years of hard work, long-term solutions are in view.

Assisted by FloodWise, city and county staff—supported by local officials and residents—worked to identify key problems and goals. They commissioned an engineering study to determine how flood risks could be minimized and used that information to apply for a highly competitive FEMA Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant.

Earlier this year, the county secured nearly $500,000 from FEMA and the state of South Dakota to finalize plans for projects that will offer lasting flood protection. In the coming years, city and county staff will take on the grueling task of shepherding the projects through permitting and construction: no small task for a county of only 9,000 people.

Though the work is far from done, securing the FEMA grant is a big win. The projects to be funded could save lives, prevent massive economic losses, and protect downstream communities. In addition, the projects will enhance nature parks and stream access for the benefit of the community and 2 million annual visitors.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Rural communities are up to the challenge

The county’s success shows what rural communities can do. Some people assume that rural communities can’t overcome problems—or implement solutions—of this scale and complexity. Like other rural municipalities that have taken on similar challenges, Custer proves they can. Though rural communities may lack financial and technical resources, time and again rural people demonstrate a wealth of tenacity and insight, enabling them to tackle even the most monumental tasks.

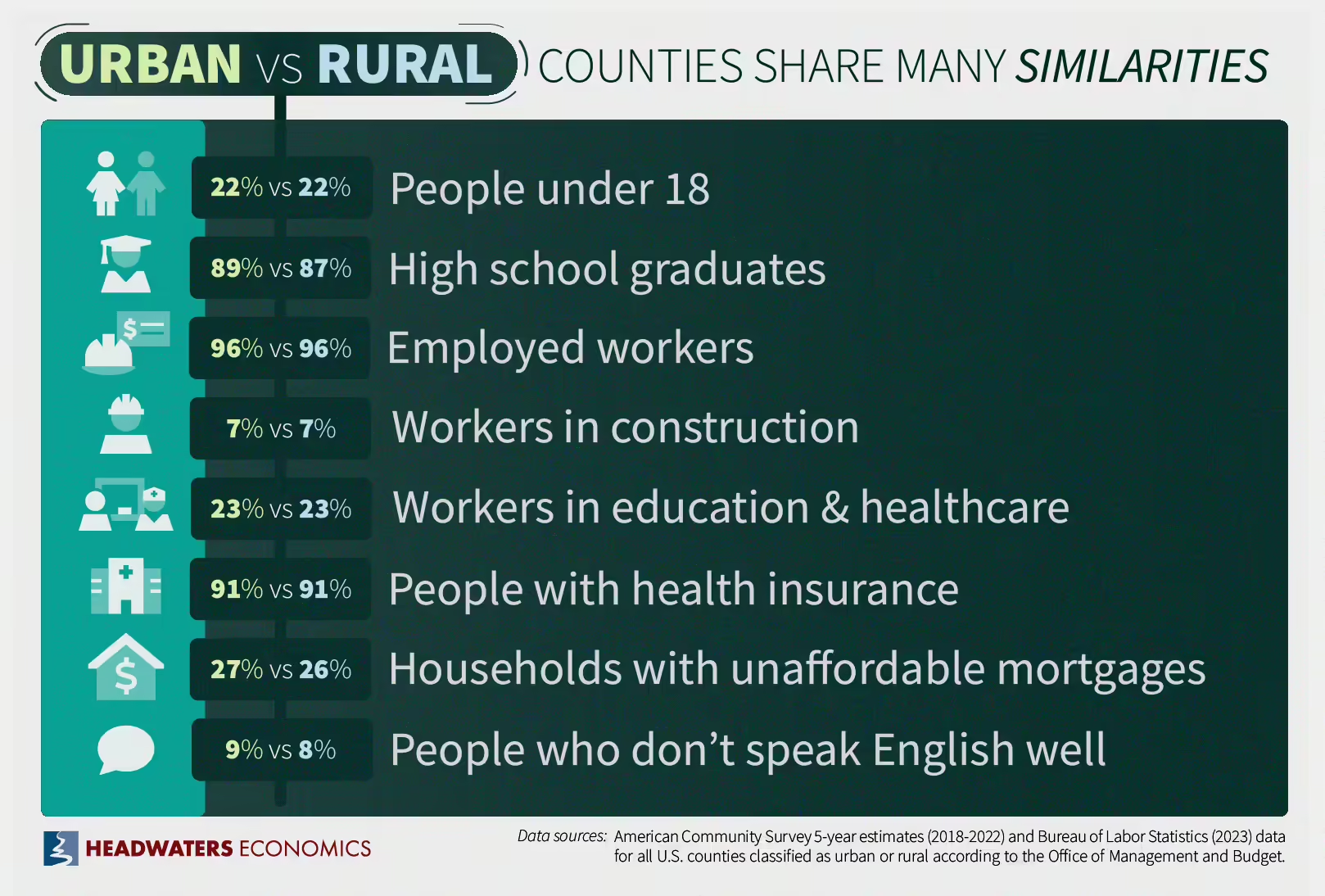

Assumptions about rural communities and their capabilities are rooted in stereotypes about stark contrasts between country and city. Those stereotypes break down when you look at the data. In metropolitan and rural areas alike, for example, people graduate from high school at nearly identical rates. Nearly identical percentages of people work in fields like construction, retail, education, and health care. And nearly identical percentages have no health insurance or struggle with unaffordable mortgages.

Across the United States, people in both cities and rural areas are devoted to, and amazingly effective at, improving the quality of life in their communities. They want good neighbors, a clean environment, and a thriving economy. They want the best for their children and grandchildren. When their communities face difficulties, they stand strong, determined to solve problems and find solutions.

What makes rural challenges unique

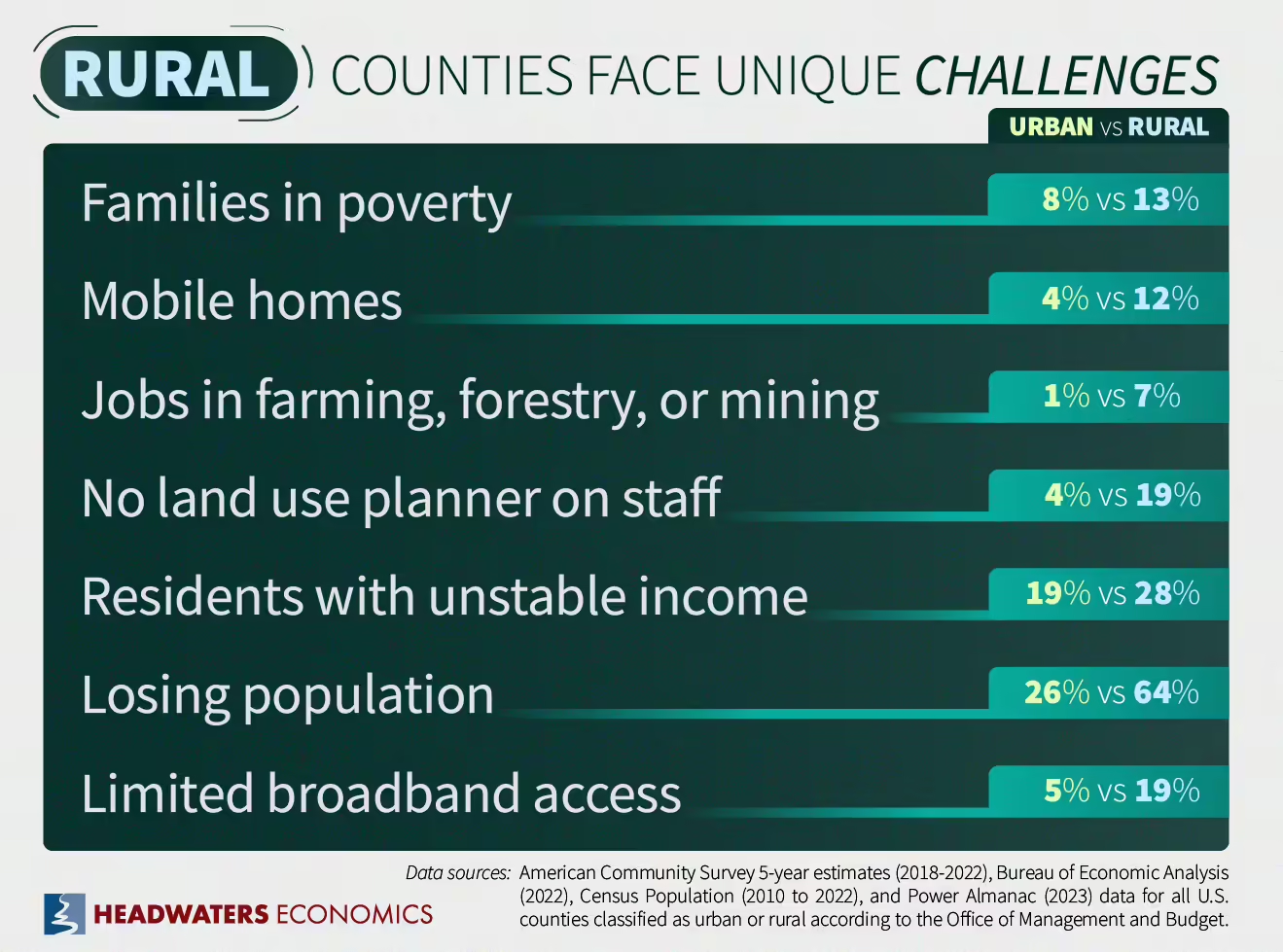

In many rural communities, as in many urban neighborhoods, decades of underinvestment have damaged local economies and diminished residents’ quality of life. And rural communities also contend with additional challenges.

Population numbers are dropping in more than half of rural towns but holding steady or growing in nearly two-thirds of cities. In rural areas—which may have similar infrastructure needs as cities but smaller and often shrinking tax bases to pay for them—disinvestment takes forms rarely seen in metropolitan areas. Rural communities still lag behind in broadband connectivity and utilization, for example, which hampers economic development and business growth.

And disinvestment continues. Per capita, the philanthropic sector spends less than half as much in rural areas as it does elsewhere. Though new philanthropic collaboratives are exploring how to work with rural communities, few national foundations have made serious investments.

Rural communities are also at higher risk for certain types of disasters, such as wildfires and tornados, and have other unique vulnerabilities as well. Many rural economies are dependent on a single industry like agriculture or timber, for example, and disruption of that industry can devastate incomes across a wide geographic area.

When a disaster does strike, it can be difficult for rural communities to secure support. Rural governments often don’t have the budget flexibility to absorb an unexpected shock like a disaster, and there are often long delays between when disasters strike and when federal aid is received. In many cases smaller communities are disproportionately impacted by disasters but struggle to meet thresholds or secure necessary documentation to qualify for recovery support. Plus, in small towns and sparsely populated counties, local governments rarely have the capacity—the staff, resources, and technical know-how in areas like engineering and grant writing—needed to pursue funding like the FEMA BRIC award secured by Custer.

A down payment on our shared future

In rural communities, as in urban neighborhoods, smart investments are a key ingredient in lasting solutions to a wide range of challenges, including the growing risk and severity of natural disasters. To make a difference in places like Custer, funders need to prioritize investing in communities that need assistance. Using tools like the Rural Capacity Map, they can make well-informed, data-driven decisions about how to allocate dollars.

In Custer, solutions are being forged by the grit of local people, the capacity boost provided by FloodWise, and the investment made by FEMA and South Dakota. This blend of forces can do far more than repair recent damage. Collaborative efforts can leverage long-term results, helping communities prevent future damage and design resilient infrastructure.

With investment and support, rural people consistently demonstrate the ability to think big, strengthen the fabric of their communities, and redesign their economies for long-term success. Smart investments in capacity and partnerships can help rural communities realize ambitious goals and navigate projects that improve well-being, create opportunity, and boost community pride. These investments matter, not just to rural towns and counties but also to the nation. After all, much of the U.S. economy depends on goods and services produced in rural communities.

We are all connected economically and materially, with rural areas yielding food, energy products, and services for domestic use and export markets. We are connected politically, with rural states and districts wielding real power: a Wyoming voter has more than three times as much clout as a California voter in the Electoral College, and more than 60 times as much clout in the Senate. And we are connected socially and culturally, by friendships, by family ties and histories, and by the rural landscapes and lifeways at the heart of many of our deepest understandings of America.

Reversing the legacy of rural disinvestment—and deliberately designing solutions for rural America—is a down payment on our shared future.

Data Sources and Methods

This essay compares urban and rural counties in the U.S. using socioeconomic data reported in Headwaters Economics’ Economic Profile System (EPS).

To delineate Urban and Rural counties, EPS uses the 2013 Office of Management and Budget (OMB) metropolitan statistical area county classification. Urban counties are defined by the OMB as Metropolitan Statistical Area Central or Outlying counties. The remaining counties are considered rural.

The OMB defines Metropolitan Statistical Areas as counties (or equivalent entities) that are associated with at least one urbanized area of at least 50,000 population, plus adjacent counties having a high degree of social and economic integration with the core as measured through commuting ties. A county qualifies as Metropolitan Statistical Areas Outlying under the following circumstances: (1) one-quarter or more of the employed residents work in the central counties of the metropolitan statistical area, or (2) one-quarter or more of the employment is composed of workers who live in the central counties.

Read complete definitions from the Census Bureau. Downloadable tabular data (“Delineation Files“) are also available.

The data sources for the demographic and economics comparisons are as follows.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2022

People under 18; High school graduates; People with health insurance; People who work in construction, education, healthcare, and social assistance; Households with unaffordable mortgages; People who don’t speak English well

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Data Tables, 2022

Residents with unstable income; Jobs in farming, forestry, or mining

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, 2023

Employed workers

Source: Power Almanac, 2023

No land use planner on staff

Special thanks to Tovar Cerulli for writing assistance.