The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), is the United States’ flagship pre-disaster grant program. Since 2020 BRIC has allocated more than $5 billion for investment in community projects that can alleviate human suffering and avoid economic losses from wildfire, floods, and other disasters. BRIC is a relatively new and innovative program, and while it receives far fewer resources than post-disaster mitigation programs in the United States, an examination of its latest round of funding selections demonstrates a growing and unmet need for projects that reduce disaster risk in communities throughout the country.

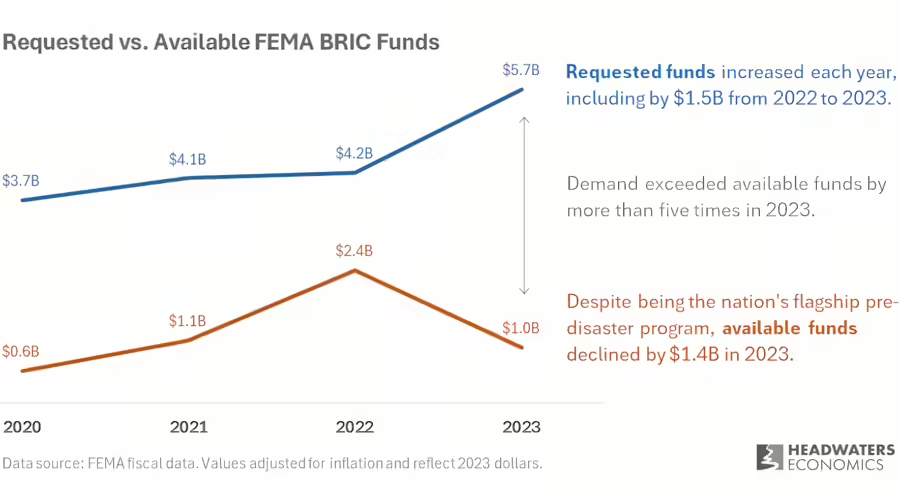

Headwaters Economics analyzed this year’s selections, building on our previous analyses, to assess trends in the number of applications for BRIC funding, the geographic distribution of funds, and the ability of local governments to secure funding. Our findings show that the demand for pre-disaster, risk reduction investments is increasing. The total funding that communities requested in applications submitted to FEMA exceeded BRIC’s available funds by more than five times in the latest round of funding.

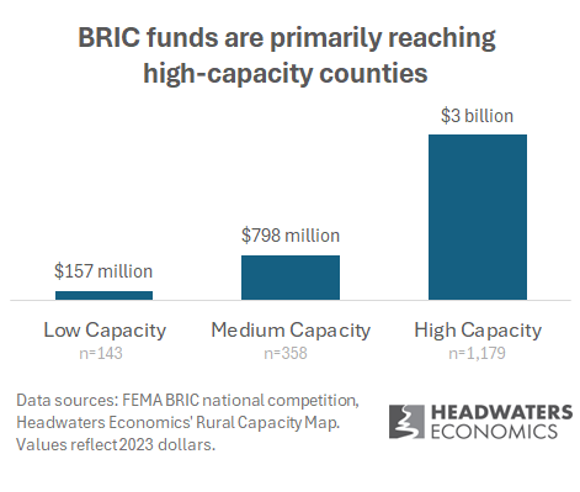

We also found that many low-capacity communities, those with limited city staff and resources, continue to struggle to access BRIC grants:

- Low-capacity counties received 19 times less BRIC funding than high-capacity counties. Across the four rounds of funding, $3 billion in national competition projects will benefit high-capacity counties, compared to $157 million for low-capacity counties.

- In the latest round of funding, 67% of BRIC funding is slated for East and West Coast states compared to 33% for Interior and Gulf Coast states.

- BRIC funding earmarked for states is often unallocated. Only 17 states have used 90% or more of their state allocation funds across the four rounds of BRIC funding, and four states (Kentucky, Montana, New Hampshire, and West Virginia) have used less than half of their total allocated funds.

Demand for BRIC’s pre-disaster, risk mitigation funding is increasing

BRIC launched in FY2020 with a total budget of $500 million, representing a groundbreaking increase in funding for projects that help communities reduce risks from a range of disasters, many of them increasing in frequency and severity. COVID recovery funding bolstered the program in subsequent years – to $1 billion in FY2021 and $2.3 billion in FY2022, and then back to $1 billion in FY2023. Respectively, the corresponding values in 2023 dollars are $586 million, $1.1 billion, $2.4 billion, and $1 billion.

Each year the requests made by communities to BRIC have increased, outpacing available funding. In this latest funding round, more than 1,200 communities submitted applications to BRIC, totaling more than $5.7 billion in requests. Of the applications submitted, 718 requests summing to $1 billion in planning and implementation projects were selected for further review – leaving more than $4.7 billion in unfunded community needs.

Local government capacity stands out as a barrier to accessing BRIC funding

FEMA’s BRIC program has made critical disaster resilience investments throughout the United States. However, FEMA’s budget for BRIC has been volatile between funding rounds, creating planning challenges for communities that are uncertain about the availability of funds in the future. Applying for BRIC funding is complicated and time intensive, sometimes requiring 12 months or more to assemble components of the application. Many communities lack the capacity to even evaluate their eligibility, much less develop competitive proposals and navigate the application process.

The latest BRIC selections demonstrate that higher-capacity communities continue to be more successful at accessing BRIC funding. For example, many higher-capacity communities have secured multiple national competition awards over the four rounds of funding. New York City has received 14 separate BRIC awards totaling $429 million, Philadelphia has received five awards totaling $139 million, and Sacramento has received four awards totaling $110 million.

Using FEMA’s data, Headwaters Economics compared the national BRIC competition awards to the Rural Capacity Index to understand how the grant program is benefiting lower-capacity counties. Across the four rounds of BRIC funding, $3 billion (76%) will benefit higher-capacity counties, $798 million (20%) will benefit medium-capacity counties, and $157 million (4%) will benefit low-capacity counties.

FEMA has recognized that capacity barriers limit program access and is working to streamline the BRIC application process, such as by waiving the benefit-cost analysis requirement for projects less than $1 million in total cost and expanding its Direct Technical Assistance program. Notably, in this funding round, FEMA selected 67 communities, three territories, and 23 tribal nations to participate in its Direct Technical Assistance program. These investments in technical assistance are key to improving access to BRIC funding.

BRIC allocations continue to favor coastal states

FEMA designed BRIC to fund large, ambitious resilience projects, and by design, the program will have geographic disparities in any given funding round. However, this analysis found patterns in round after round where the same states—and in some cases the same communities—are securing funding repeatedly, leaving many other regions behind. While BRIC is a relatively small grant program within the larger field of federal competitive grants programs, these patterns reinforce broader trends of regional disinvestment in the U.S.

In this latest round, every state applied for and received funding from the BRIC program. But 67% of funds went to states on the East and West Coast whereas only 33% of funds went to Interior and Gulf Coast states. While states in the Southwest and Intermountain West (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, and WY) face worsening droughts and wildfires, they struggled to access BRIC funding in this funding cycle. These states requested more than $443.5 million, but only $29 million in project costs were selected—approximately 3% of FEMA’s FY2023 budget for BRIC.

The three states that received the most BRIC funding (California, New York, and Louisiana) collectively will receive 50% of BRIC’s total budget. The bottom 30 states collectively secured less than 10% of the total funding.

Across the four funding rounds, patterns of which states can secure funding—or not—are emerging. The two tables below show the five states that have received the most funding and the five states that have received the least funding in each funding round and across all funding opportunities within the BRIC program.

Top 5 BRIC Recipients by Funding Round

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| California | California | California | California |

| New Jersey | Utah | New York | New York |

| Washington | New York | Florida | Louisiana |

| District of Columbia | Florida | Oregon | Pennsylvania |

| South Carolina | Washington | North Carolina | Maryland |

Lowest 5 BRIC Recipients by Funding Round

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | Kentucky | West Virginia | Mississippi |

| Minnesota | Tennessee | Kentucky | Tennessee |

| Oregon | Rhode Island | New Hampshire | Missouri |

| Maine | Arizona | Delaware | New Hampshire |

| Montana | West Virginia | Rhode Island | Arkansas |

The graphic below shows the total funding received by each state for the fourth cycle of funding. You can change the drop-down menu to view different funding rounds or view all four rounds combined.

BRIC funding available to every state often goes unallocated

In addition to its national competition grant program, BRIC has allocation funding for states and U.S. territories. In the first funding round, each state could apply for up to $600,000 in state allocation funds. The state allocation amount expanded to $1 million per state in the second round of funding and then $2 million per state in the third and fourth rounds.

Communities typically use state allocation funding for planning, scoping, or designing projects since most implementation and construction proposals exceed the $2 million cap. Strategies for applying to the state allocation pool differ from state to state, with most states adopting internal ranking systems to decide which applications to submit to FEMA.

Applications submitted for state allocation funds are far more likely to be funded than in the national competition pool. Over the four funding rounds, the selection rate for state allocation funded applications was 86%, compared to 14% for the national competition.

Despite higher approval rates, many states have struggled to secure their full allocation. Collectively, only 17 states have used 90% or more of their state allocation funds in the four rounds of BRIC funding. In the fourth funding round, eight states received less than half of their state allocation: Alabama, Alaska, Hawaii, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, and Tennessee.

Reasons that a state may not use their full allocation range from submitting applications that do not meet FEMA requirements, requesting only partial amounts of the allocation, and struggling to identify projects that fit within the limited budget. State capacity, including the number of state employees available to help identify projects and assist with grant writing, varies widely and can also limit the ability of states to successfully use their allocated funds.

Solutions to improve access to BRIC and other federal resilience funding

Consistent with Headwaters Economics’ prior research on BRIC, this analysis reveals an increasing demand for pre-disaster investments and sheds light on the difficulties that lower-capacity parts of the country face when trying to access resources. Solutions include steps to simplify the application process, reduce the need for communities to find matching funds, increase state assistance and allocations, and build local government capacity and thus their ability to secure funding.

Solutions to improve access to BRIC and other federal pre-disaster programs

Simplify applications and reporting. FEMA has already made changes to its application and selection process to ensure better access to the program, but further streamlining is needed. Simplified application and reporting requirements would enable more rural, disadvantaged, and lower-capacity communities to apply. FEMA can also combine the BRIC and Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) applications into one form to improve access to both programs. The U.S. Forest Service’s Community Wildfire Defense Grant tool offers an example of one federal strategy being used to reduce the administrative burden. This free online resource informs communities whether they are eligible for the grant and, if so, provides the data they will need to fill out the application.

Reduce or waive grant match requirements for more communities. Local match requirements prevent many rural and low-capacity communities from applying for federal grants. While BRIC offers a reduced local match for small, economically disadvantaged communities, the eligibility requirements are too restrictive. Reducing and waiving the local match requirements for more communities would make the program more accessible. State governments can further help lower-capacity communities by creating programs to assist with local match requirements for federal grants. For example, Texas’s Infrastructure Resiliency Fund provides funding that communities can use to pay for federal local match costs.

Increase state, territory, and tribal allocations. BRIC’s state, territory, and allocation funding ensure more inclusive distributions and also enables smaller but critical mitigation projects – such as culvert replacements and feasibility studies – to be funded without having to compete at the national level. Increasing the state, territory, and tribal allocation portions of BRIC would enable more of these types of projects and expand the geographic reach of BRIC.

Create more technical assistance for low-capacity communities. BRIC’s direct technical assistance program is providing critical services to rural and lower-capacity communities, but its reach is limited. FEMA needs more resources and staff to meet the need. FEMA could invest in partnerships with more nonprofit organizations, regional hubs, and navigator programs to ensure that communities with limited resources are able to access federal funding programs. Given the rise in funding and grant programs across federal agencies, FEMA can also take a lead in interagency coordination and help match communities with funding for their projects that reduce disaster risk and strengthen resilience.

Solutions for building capacity

Invest in local and state mitigation capacity. States play an outsized role in BRIC funding distributions, but many state agencies lack the staff and resources to assist their rural, disadvantaged, and lower-capacity communities. FEMA’s Emergency Management Performance Grant is used by many states to fund local and state emergency management personnel and mitigation efforts, but funding levels have not kept up with needs and are often unpredictable from year to year. Congress can build local and state capacity for emergency management and mitigation by increasing funding for this program and authorizing it for multiple years. FEMA can also establish cooperative agreements with state governments or regional entities to directly fund more local mitigation staff. Without direct investments in staff, many communities—particularly those that are rural or disadvantaged—will likely be left behind in the nation’s efforts to reduce disaster risk and build resilience.

Integrate capacity considerations into federal vulnerability maps. Local government capacity is an important dimension of need that has not yet been incorporated into federal vulnerability maps, such as Community Disaster Resilience Zones (CDRZ) and Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST), which help prioritize the allocation of BRIC and other federal funding programs. Accounting for local government capacity in grant and technical assistance prioritization could increase accessibility to programs that struggle to reach many rural and disadvantaged communities.

Fund regional organizations and promote multi-jurisdictional projects. Funding regional organizations and projects that leverage urban-rural partnerships to decrease disaster risk can strengthen capacity in low-capacity communities. Regional approaches often face high organizational expenses due to the time and cost of coordinating across government jurisdictions and multiple stakeholders. FEMA and other federal agencies can support these critical approaches by offering more operational funding and providing application templates to encourage regional submissions, including directions for how to conduct a benefit-cost analysis for watershed-scale efforts. State governments can also help support and coordinate regional approaches by providing funding, staff, and other resources.

Address the root causes of low capacity. Low-capacity communities have often experienced decades of disinvestment, resulting in inadequate infrastructure, economic dependence on narrow sectors, and local governments that can barely meet community needs and day-to-day operations. By prioritizing projects that address the root causes of vulnerability and low capacity, BRIC and other federal funding programs can help communities address inequities within their community, generate predictable local revenue needed to maintain infrastructure and adaptation projects, and strengthen trust in local government. Through eligibility and scoring criteria, FEMA can encourage projects that create long-term economic benefits through new jobs, affordable housing, and local amenities like outdoor recreation.

Expand and diversify mitigation funding. Demand for BRIC funding has outstripped the availability of funds in every grant cycle. Levels of BRIC funding have also been unpredictable from year to year, making it hard for communities to develop sound funding strategies. Congress can provide FEMA with consistent funding to alleviate this uncertainty. Further, many rural and lower-capacity communities will continue to struggle to access funding from competitive grants. FEMA and other federal agencies can address these equity issues by allocating mitigation funding through noncompetitive mechanisms such as direct allocations and formula or block grants.

Given the consistent increase in demand for BRIC support and the low rate of success by low-capacity places, efforts to improve access to BRIC in places like the Interior and Gulf Coast could help generate broad bipartisan support for this and other federal pre-disaster programs. Communities are facing increasing risks from hazards, and programs such as BRIC will be vital to protecting lives, property, local economies, and quality of life in the near and longterm.

Data sources and methods

Data about FEMA BRIC applications are from the OpenFEMA Dataset and were accessed July 2024. This analysis includes the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia and does not include U.S. territories. The analysis does not include Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) awards, though FEMA can fund BRIC proposals through that program.

The OpenFEMA Dataset includes updates to state totals from previous years. Headwaters Economics’ previous analyses used preliminary selection data that has changed, so numbers presented in this analysis may be slightly different than totals in previous posts.

Where noted, dollar figures are adjusted for inflation and represent 2023 dollars.

Rural Capacity Index scores were pulled for the reported benefitting counties for each project funded. When there were multiple benefitting counties for one project the lowest Rural Capacity Index score was chosen.