Building funding strategies for flood mitigation projects

September 2020

Flooding is the most common and expensive natural disaster in the United States. Mitigation projects—which encompass a range of preventive solutions—are the most cost-effective strategy for decreasing flood risk. According to research conducted by the National Institute of Building Sciences, for every $1 that the federal government spends on flood mitigation, it saves $6 in avoided costs if a flood were to occur. The amount of community stress and heartbreak these projects prevent is unquantifiable.

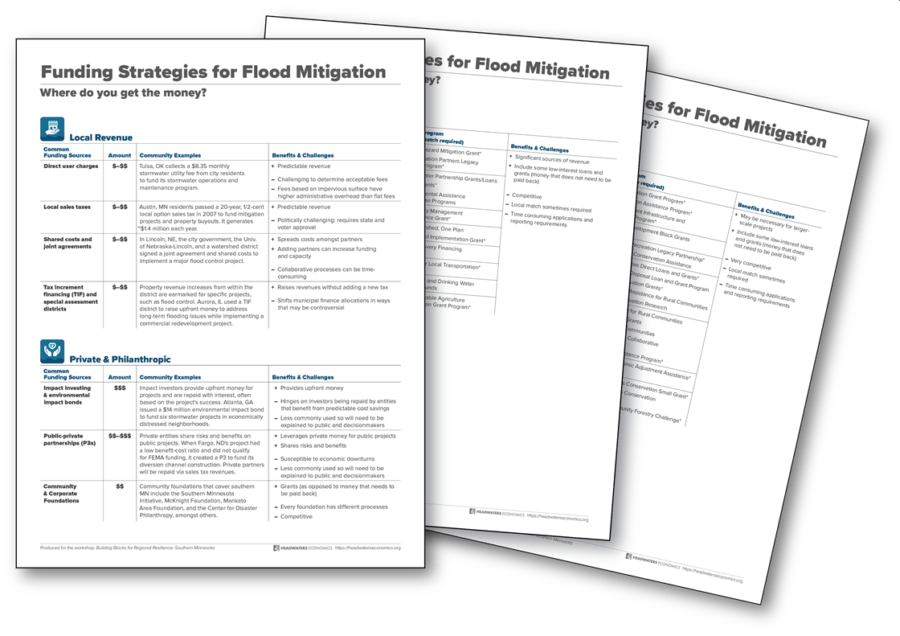

While mitigation projects make long-term financial sense, they can be challenging for communities to implement. In spring 2020 Headwaters Economics interviewed more than 60 community leaders, researchers, and policy experts to learn about successful mitigation projects. They repeatedly identified funding as a challenge. The video and text below—created for the workshop series, Building Blocks for Regional Resilience in Southern Minnesota—summarize two key components to building a funding strategy for flood mitigation projects: where to get the money, and how to get the money.

Where do you get the money?

The most successful funding strategies for mitigation projects have long-term, predictable funding from a variety of local, state, federal, and private sources. Read more below, or download this summary table.

Local Funding Sources

The range of local funding sources available to communities depends on the state’s fiscal policies and the local context. Not every state allows local sales taxes. For those that do, it can be an effective revenue source. For instance, Austin, Minnesota’s local option ½-cent sales tax raises $1.4 million annually, which it uses to fund flood control projects. Other cities, such as Tulsa, Oklahoma, charge residents a monthly stormwater utility fee to help fund ongoing stormwater maintenance. Passing new taxes or fees often requires significant community outreach but can be critical funding sources.

Other ways to raise local money include impact fees, tax increment financing (TIF) or special assessment districts, joint agreements, or simply re-prioritizing existing budgets. Loans and bonds can also generate upfront money.

Local revenues are important because they give communities predictable revenues that enable more control over the project. Additionally, local revenues can be used as matches for state and federal grants.

State and Federal Funding Sources

Larger projects, particularly those with highly engineered solutions, typically require a mix of state and/or federal grants and loans. State and federal grants can provide significant up-front money but are often very competitive. Applications can be complicated and time-consuming, and record-keeping and reporting requirements are lengthy, particularly for federal grants. Many state and federal grants require communities to provide money as a “local match” – typically between 25 and 30% of the total project cost.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is the go-to federal agency for disaster recovery and hazard mitigation assistance. FEMA has three funding programs specifically for flood mitigation:

- The Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP)

- The Flood Mitigation Assistance Program (FMA)

- And the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities Program (BRIC) – the replacement program for the Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) Program

In addition to FEMA, other state and federal agencies have grants and loans that can be used for flood mitigation projects. For instance, many communities have used Community Development Block Grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to fund mitigation projects. Similarly, economic development agencies can be leveraged when flood projects help protect jobs and economic activity. The website grants.gov allows users to use keywords to easily search all federal grant opportunities for flood-related funding.

Private Funding Sources

Private sources of funding are often overlooked by communities but can be substantial. For instance, the Cedar River Watershed District in Minnesota received more than $3 million in grants from the Hormel Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the Hormel Foods Corporation. These investments have helped the Watershed District fund 25 mitigation projects identified in its master plan. Bank branches, corporate chain stores, and local cooperatives often have foundations or philanthropic programs.

How do you get the money?

Funding applications and proposals are stronger when they include effective economic arguments. Funders have different values and funding priorities. Tailoring funding requests to different funders is a key component of building a successful funding strategy. The charts below provide examples of the messages that matter to different funders and the types of data that can be used to strengthen these arguments.

Local elected officials

Target messages around community health, safety and welfare; budgets; competing demands and priorities; electability. For example:

- Project creates jobs and brings new funding

- Protecting our community is worth the cost

- Project is a win-win

- Project complements other municipal plans and departmental strategies

- Project reduces impacts of climate change on underserved neighborhoods

Evidence to support the message:

- Show impact on city budgets.

- Use neighborhood-level data and data from peer municipalities.

- Estimate money saved from having project in place (cost avoidance study).

Local taxpayers

Target messages around fees; taxes; quality of life; and community stability. For example:

- A small investment now will avoid tragedies with enormous costs in the future

- Your neighbors are participating

- Project will provide safe and reliable infrastructure

- Project will improve neighborhood safety

Evidence to support the message:

- Show that similar projects have increased property values in other communities.

- Point out savings from decreased flood risk and lowered insurance premiums.

- Share data from questionnaires, surveys, and comments from public meetings.

Local business owners

Target messages around regulatory predictability, economic impacts and efficiency, and debt avoidance. For example:

- Project creates jobs

- Good return on investment

- Local economic drivers will be sustained

- Project will bring new people to the area

Evidence to support the message:

- Get data showing trends in population and employment and show how project will contribute to economic development.

- Estimate jobs and income protected or created as a result of the project.

State and federal partners

Target messages around quantifiable costs and benefits; reliable data; logistical procedures. For example.:

- Protecting your community is worth the cost

- Doing Y will most likely result in Z

- Avoidance of damage and expenses from natural hazards

- Project increases safety of people and infrastructure

Evidence to support the message:

- Get letters of support to demonstrate community buy-in.

- Compare costs of different actions to achieve a specific goal.

- Estimate cost-effectiveness through a benefit-cost analysis.

- Estimate positive impacts on amenities that people value, such as health and clean air.

Foundations, philanthropists, impact investors

Target messages around climate change impacts on people and the environment; obligations to future generations; equitable outcomes; environmental stewardship. For example:

- Climate change is threatening the world as we know it—we must ac

- Project improves racial and environmental justice

- Project improves clean air and water, abundant wildlife

- Project provides green infrastructure, alternative energy

- Project is the right thing to do for future generations

- Project supports neighborhood decision-making

Evidence to support the message:

- Show how the project will benefit underserved individuals and neighborhoods.

- Take compelling photos, organize site visits, get quotes from community members.

- Show how the philanthropic investment will serve as a catalyst and be leveraged to secure additional funding.

- Explain who will bear the costs and who will receive the benefits.

Mitigation projects often result in multiple benefits for communities and regions. Common benefits from mitigation projects include improved water quality, restored wetlands, economic development opportunities, improved hunting and fishing habitat, and new recreational opportunities such as parks or trails. Identifying a range of benefits can help build support and increase potential funding sources.

Finally, relationship-building is key. Building relationships with federal and state program officers and district representatives is important. Call them to discuss the project before writing a proposal. Once a grant has been received, meet periodically with program officers, send updates, and invite them to site visits.

Download this summary table to read more considerations for tailoring messages and to different funding audiences.

Conclusion

Mitigation projects come in all shapes and sizes. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, the city uses revenue from its stormwater utility fee to fund stormwater improvement projects and maintain its extensive network of detention basins. These basins provide floodwater storage during heavy rain events and function as sports and recreation fields during normal times. Other projects are much larger. For instance, the Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Project includes a 30-mile diversion channel, a 20-mile southern embankment to regulate flood water flows through the metro area, and in-town levees in Fargo and Moorhead. This massive mitigation project spans over two states and is estimated to cost over $2.7 billion.

Developing funding strategies for mitigation projects helps communities prepare themselves for the future and reduce their risks to hazards. Because local budgets are often tight and grants are competitive, project teams must be creative. Building a strategy that uses diverse and predictable funding sources, including significant revenue from local sources, can strengthen projects. While these projects can be expensive and time-consuming to implement, its is more effective to prepare for disasters today than repeatedly spending money on disaster recovery.