Update May 21, 2025: This post has been updated to reflect refinements to the original analysis. See Data Sources and Methods section below.

Since 2020, communities across the country have faced unprecedented increases in housing costs due to high demand, supply chain disruptions, construction labor force shortages, and other factors. Gateway communities to national parks and public lands face additional headwinds, sometimes lacking suitable private land where new housing can be built.

Both the Trump and Harris campaigns in 2024 proposed building housing on public land as one possible solution to the housing crisis, although there is a lack of consensus among lawmakers in both parties and broad public opposition to selling public land. To a limited degree, existing laws such as the EXPLORE Act and the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act already authorize leasing or sale of federal land for housing. In March 2025, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) announced a joint task force to identify DOI land that could be suitable for residential development.

Given the acute housing challenges communities face and the attention federal lands are getting from policymakers, Headwaters Economics investigated how much federal land is suitable for housing and whether it can meaningfully improve housing affordability. Our findings show that opportunities are limited to a few states, and are complicated by wildfire and drought risks, as well as other development challenges. Federal land will not solve all housing goals and will require guardrails to protect taxpayer value and long-term housing durability and affordability.

Housing potential on federal public land is limited and highly constrained

To evaluate whether national public land could help reach housing goals, Headwaters Economics identified federal public land near communities where housing production has lagged behind demand, including in rural places and smaller but rapidly developing gateway communities near national parks and other natural amenities. We examined Forest Service operational lands and select Department of Interior (DOI) lands (including Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) land) within a quarter-mile of towns with unmet housing needs and a population of at least 100. (For additional detail see the Data Source and Methods section below.) Our analysis finds opportunities are limited to a few states in the West and further hindered by high wildfire risk.

More than half of the federal land near communities with housing needs has high wildfire risk.

Less than 2% of the 181 million acres of Forest Service operational and Department of Interior land included this analysis are close enough to towns with housing needs to be practical for development—around 2.4 million acres. Most of this land is concentrated in a handful of western states—primarily Nevada, Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Utah—and the vast majority of the land is managed by DOI. Forest Service lands offer even fewer options, with only three states (Arizona, Utah, and Oregon) having more than 5,000 acres near towns.

However, beyond proximity, safety is an important consideration. More than half (58%) of the federal land near communities with housing needs also faces high wildfire risk, leaving only about 1 million acres realistically available for safe development. Many of these places also face other hazards, such as flooding and drought.

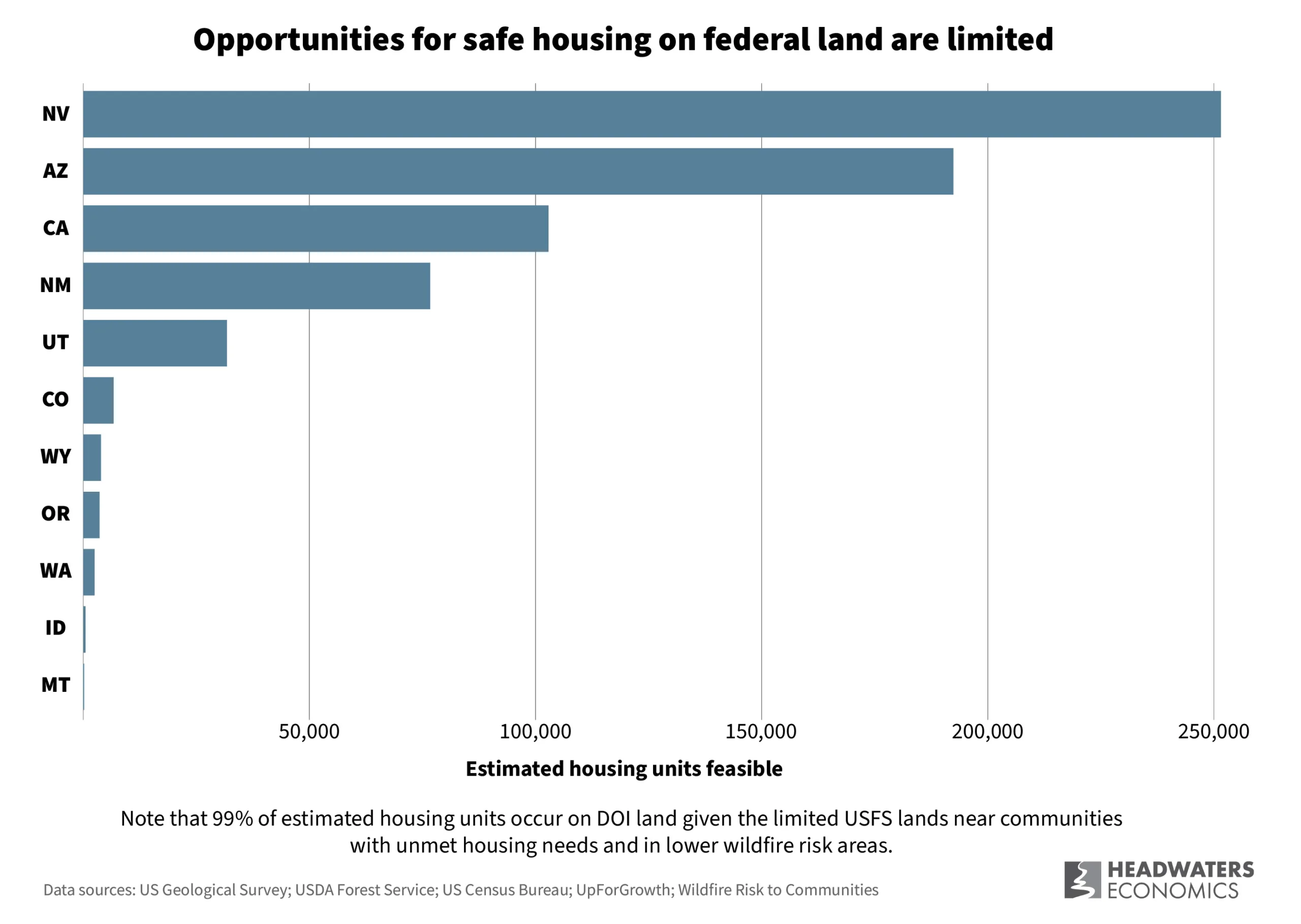

The number of homes that could realistically be built on these public lands is limited. Applying a conservative density estimate of 0.66 housing units per acre—the Census standard for defining urban core areas—and assuming areas with high wildfire risk should be avoided, we estimate fewer than 700,000 new homes could be built on the suite of federal lands that are near Western towns and cities with unmet housing needs. The potential is concentrated in just a handful of states: Nevada, Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Utah.

Whether there is a real opportunity to improve housing affordability by building homes on these lands depends on a host of local factors. Essential considerations include whether there is enough water to support new development, builders willing to develop housing at affordable price points, and a labor force to construct new housing. In many communities with unmet housing needs, a lack of available land is not actually the barrier.

Much of this federal land is also currently used for agricultural or resource leases, or for water or wildlife protections, posing legal and fiscal constraints to alternative uses including housing. Finally, proposed projects must align with communities’ interests in preserving access to outdoor recreation and natural areas. Local opposition will further decrease the set of federal lands appropriate for home development.

Necessary guardrails to housing on federal land

Developing housing on public lands may offer benefits in a limited number of communities, but it is not a broad solution. While access to low-cost land can help, housing affordability depends on a complex set of factors—such as construction and labor costs, financing availability and interest rates, insurance access and affordability, and proximity to jobs. In addition, hyperlocal constraints like water supply and community opposition can further restrict feasibility.

Where federal lands are already being considered for housing, projects are often highly complex and can take many years to move forward. In the few areas where using public lands for housing may be appropriate, clear policy guardrails should be established to guide decision-making and implementation, including the following:

Ensure long-term affordability of housing on public lands

More housing does not automatically mean more affordable housing—especially in desirable, high-amenity rural areas—so any housing built on public land must come with permanent affordability guarantees. To ensure affordability, policymakers should:

- Require deed restrictions, community land trusts, partnerships with housing agencies, or other affordability tools for housing developed on federal lands to ensure long-term benefits for local workers and residents.

- Provide subsidies or tax incentives, and technical support for developers to access these programs, to support long-term affordability.

Prioritize infill first

Before considering the use of federal lands, communities must first maximize opportunities to build housing within existing boundaries. Infill and the redevelopment of underutilized sites make more efficient use of infrastructure, lower long-term taxpayer costs, and support walkable, affordable neighborhoods. To protect open space, reduce wildfire exposure, and improve housing affordability, local governments can take several steps to expand housing options within their communities’ existing neighborhoods:

- Adopt zoning reforms that allow for smaller lots and a mix of housing types, such as duplexes and fourplexes.

- Limit short-term rentals and incentivize long-term rentals to stabilize housing supply and affordability.

- Prioritize redevelopment of vacant or underutilized sites to make more efficient use of land and infrastructure.

Protect public value for the long term

Federal public lands are a national asset held for the benefit of all Americans. They deliver lasting economic, ecological, and cultural value, safeguarding clean drinking water, supporting working landscapes for timber, grazing, and mining, and providing unmatched access to recreation—including hunting, hiking, and camping—which fuels a $1.2 trillion outdoor recreation economy.

Selling these lands for short-term housing gains risks forfeiting these long-term public benefits. Once sold, public lands are unlikely to be recovered—and the ecological, recreational, and economic functions they provide may be lost permanently. To preserve taxpayer value and future options, policymakers should:

- Require clear safeguards, ensuring that development cannot proceed without confirming protection of critical resources like water supplies, wildlife habitat, and public access to recreation.

- Use strategic land swaps that protect high-value resources—such as watersheds, wildlife habitat, and working forests or rangelands.

- Prioritize leasing over permanent sales, preserving taxpayer value and potential revenue for future generations and giving the federal government authority regarding the density and affordability of housing that is built.

- Dedicate any financial proceeds to a permanent public lands endowment, with the principal protected and interest reinvested in public benefits like conservation, land stewardship, or affordable housing.

Ensure housing is durable and does not put people in harm’s way

In rare cases where communities have limited options for growth, carefully planned housing may be viable on adjacent public land. In these instances, new housing must be built to last and not exacerbate existing wildfire and drought risks. To ensure housing is durable, policymakers should:

- Support grant programs and technical assistance to help communities invest in long-term durability.

- Require wildfire- and drought-resistant building practices. Defensible space requirements, landscaping codes, building codes, and infrastructure requirements can help ensure long-term durability.

Tailor solutions to community realities

Communities face a wide range of housing challenges, but the drivers often differ significantly between rural and urban areas. While some towns struggle with land availability, other unrelated barriers can further limit options, including rising construction costs or an inability to attract and retain a construction workforce. In many rural areas, even when land is available, the private market alone cannot deliver housing that is both affordable and financially viable to build.

Recognizing that housing constraints differ from place to place, federal policies must be flexible, locally informed, and designed to address the root cause—not just the symptom—of a community’s housing need. Solutions for expanding affordable housing on nonfederal land might include:

- Technical assistance and planning support to help rural and low capacity communities identify viable housing sites and navigate regulatory barriers.

- Incentives for builders and developers to take on projects that would otherwise be financially marginal.

- Workforce development programs to grow the local construction trades.

- Targeted financing tools like low-interest loans, grants, and credit enhancements to make affordable and workforce housing projects pencil out.

Ultimately, the appropriate use of public land—if any—should be part of a broader toolkit of housing solutions, not a standalone fix. Policies must meet communities where they are, with the right mix of land use flexibility, financial support, and capacity-building to unlock durable, affordable housing outcomes.

Data Sources and Methods

Updates May 21, 2025: This analysis was updated to remove duplicate acres in federal datasets that caused a small over-estimate of public lands suitable for housing. Additionally, we removed overlapping quarter-mile buffers in a few instances. We were also able to improve the accuracy of the assigned state for acres near state boundaries.

This analysis is based on a four-part process that relies on several assumptions, as described below. The analysis was national in scope, precluding the ability to incorporate localized information such as limitations posed by topography, water features, road access, construction workforce, regulatory barriers, economic feasibility, and community values. Therefore, this analysis likely overestimates the amount of usable land.

1. Federal public land. We first identified all federal public land that may be considered usable for housing. We examined both U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) land and Department of Agriculture land and made the following assumptions:

- Department of Interior: BLM, BOR, USFWS. Using the Protected Areas Database of the United States (PAD-US) from the US Geological Survey, we identified all land owned by the Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. We excluded other DOI agencies because their land is likely to have special protections that would preclude it from being used for housing (like national parks) or their land acreage was too small to affect the analysis.

- Department of Agriculture: Forest Service Operational Lands. Using the Forest Service Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board Land dataset we identified lands owned by the Forest Service with an “operational” designation. We limited the analysis to operational lands because administrative lands, which are a type of operational land, are the types of land already allowed to be leased for affordable housing in the EXPLORE Act.

2. Communities with unmet housing needs. We then limited our analysis of federal land to only land near communities with unmet housing needs, defined by the following two criteria:

- Near a town with a population of at least 100. We selected federal land within a quarter-mile of any Census place that has a population of at least 100, per the U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2023. While places this small may not currently have the jobs or infrastructure to support new housing, we chose this threshold as a conservative baseline to ensure even the smallest communities with potential housing needs were considered. The quarter-mile distance was used because building farther out would likely be impractical for affordable housing due to the high cost of extending infrastructure like roads, water, sewer, and electricity.

- In a county with unmet housing needs, defined as a county with housing underproduction from UpForGrowth. They define housing under production by incorporating a target number of housing units (based on current households, pent-up demand, and target vacancy rates) and available housing units (based on existing housing units that are renter- or owner-occupied and not second homes).

Approximately 2,446,000 acres of federal public land met these criteria.

3. Wildfire risk. Next, we looked at whether lands had high wildfire risk. We defined high wildfire risk as communities in the >70th percentile in the national dataset, Risk to Potential Structures (also called “Risk to Homes”) from the Forest Service’s Wildfire Risk to Communities. This dataset integrates wildfire likelihood and intensity with generalized consequences to a home anywhere on the landscape, allowing evaluation of risk whether a house is already constructed or not. While we limited the criteria to areas of high risk, places with moderate risk should still consider wildfire in the design and construction of new neighborhoods.

4. Estimating possible housing production. Finally, to calculate an estimate of housing units that could be constructed on federal land, we assumed that land would support an average of 0.66 housing units per acre (425 housing units per square mile), which is the value used by the Census to define urban core areas. While individual projects may achieve higher densities, this average offers a realistic national estimate, as it accounts for unbuildable land due to factors like topography and water features, as well as limitations related to drinking water and wastewater capacity, and space needed for transportation infrastructure such as roads and parking.