The economic challenges facing rural areas have been well documented.

And while there are many differences between rural areas, with some counties growing while others decline, some generalizations hold true in much of the country.

Compared to the nation, rural counties grow slower, job earnings are lower, the population is older, fewer have a high school degree, and their health outcomes are lower.

While many reasons help explain these rural challenges, one of the consequences of an aging population and struggling economies is the outmigration of young families and school-aged children. As a result, for many rural communities, school enrollment is down.

More importantly, the very fabric of some towns is changing. From high school football games to kids fishing in a local stream, it is hard to imagine a town thriving without the presence of children.

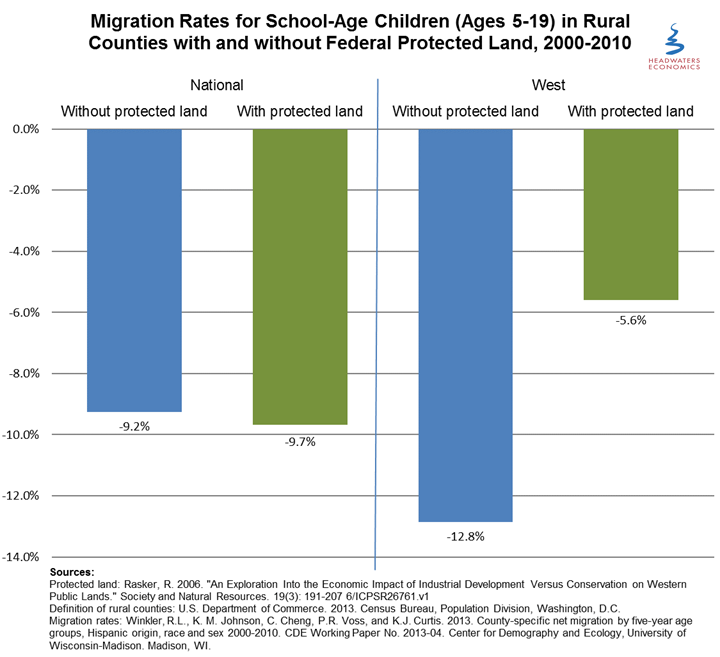

The figure below shows the outmigration of school-aged children (ages 5-19) in all rural counties in the U.S. Using Census data, from 2000 to 2010, the rate of outmigration of school-aged kids nationwide in rural counties has been more than nine percent (details below).

School Kids, Protected Lands, and the Rural West

In the West, where federal public lands make up almost half of the landscape, there is an ongoing debate about the economic role of federal lands, especially for rural communities.

The figure above also shows–for western rural counties–the difference between counties in the top quartile of protected federal lands (in the form of Wilderness, National Monuments, National Parks, and other designation that prioritize conservation) compared to western rural counties in the bottom quartile of protected federal lands.

Rural western counties with high degrees of protected lands still are losing school-aged children, but at a significantly lower rate (5.6% change versus 12.8% change for counties with few protected lands).

So while most western rural counties are aging and losing families with school-aged children, the loss of school-aged kids in rural western counties with protected lands such as National Monuments was, on average, less than half the rate of loss for similar counties without protected lands.

Conclusion: Let’s Invest in the Rural West

The challenges facing the rural West illustrate the need for smart investments and policies that can help these areas improve production, economic vitality, and quality of life important to any community.

The rural West already has many advantages such as high quality of life and lower cost of living. Unfortunately, current government and private sector approaches most often do not reflect current socioeconomic realities and often are failing rural citizens. Going forward, updated, flexible, and varied policies will be necessary to provide rural towns and communities with the resources they need to compete in today’s economy.

One of the most important issues requires improving human capital in rural communities through efforts such as investing in rural education to keep and attract families or train workers.

Other steps include increasing the quality and availability of health care; expanding and upgrading infrastructure and communications networks to help rural communities more easily access larger markets; continuing agriculture programs such as the Farm Bill; and sustaining the quality of the landscape along with best practices for utilizing natural resources.

Definitions and Additional Details

We used the 75th percentile for protected land to define “with” and “without” protected land. Nationally, this threshold is one percent of country acreage. In the West, this threshold is 11.7 percent of county acreage.

Migration rate is the proportion of a given age cohort that left the county between 2000 and 2010. For example, in the rural West, the average county with high protected land lost 5.6 percent of its schoolchildren between 2000 and 2010.

From 2000 to 2015 (latest county-level data) jobs in rural western counties grew by 12 percent overall, while job growth during the same time in metro counties grew by 21 percent. The average earnings per job in rural western counties in 2015 was $44,336, compared to $62,338 in metro counties. From 2005 to 2015, 16 percent of counties in the West lost jobs.

Rural western counties are also older, with 17.3 percent of the population over the age of 65, compared with 12.2 percent in metro counties. And, they depend more on age-related income, with 36.4 percent of households receiving Social Security (compared to 26% in metro western counties) and 22.8 percent of households receiving retirement income (16.1% in metro western counties).