Green Infrastructure: Cost-effective solutions to flooding

In the face of more frequent and costly flooding, communities need cost-effective solutions that reduce risks and contribute to well-being. Green infrastructure solutions, from wetland restoration to permeable pavement, are growing in popularity because they improve safety while creating additional community benefits such as improving water quality and access to nature trails.

What is green infrastructure?

Green infrastructure filters and absorbs stormwater. It uses landscaping rather than systems of gutters, pipes, and tunnels (i.e., “grey infrastructure”) to manage runoff and reduce flood damage. Green infrastructure can be applied at various scales, from the individual home (like rain gardens) to the broader landscape level (like wetland preservation).

However, local governments may hesitate to pursue green infrastructure projects because of a lack of information about long-term costs. Our research uncovers new data that reveal that green infrastructure projects can be cost-effective as well as durable, adaptable, and beneficial in many ways.

Green Infrastructure in Practice

Numerous green infrastructure practices can be incorporated into a site to help manage stormwater and reduce damaging floods. For example, naturalized detention basins temporally hold rainwater in a depression or impoundment and release it slowly to decrease downstream flooding from more significant precipitation events. Infiltration systems, such as rain gardens, permeable pavement, and native landscape restoration, allow rainwater to seep into the subgrade soils below. Naturalized swales, or bioswales, act as conveyance systems transporting rainwater to infiltration systems such as a detention or retention basin or a rain garden. They are designed to slow rainwater velocity, trap sediment, and sometimes infiltrate permeable and engineered soils.

However, local governments may hesitate to pursue green infrastructure projects because of a lack of information about the lifecycle costs of establishing and maintaining them. Access to clear data on maintenance costs is especially important because communities seeking federal and state grants to cover upfront establishment costs need to know they can cover the necessary maintenance in the future.

Data on maintenance costs are especially important for rural and lower-income areas with budget constraints and a lack of technical staff. The lack of data on long-term costs can lead local governments to invest in more familiar grey infrastructure such as curbs and gutters that channel water into pipes and sewers, regardless of the potential benefits of alternatives.

Green Infrastructure with Low Maintenance Costs

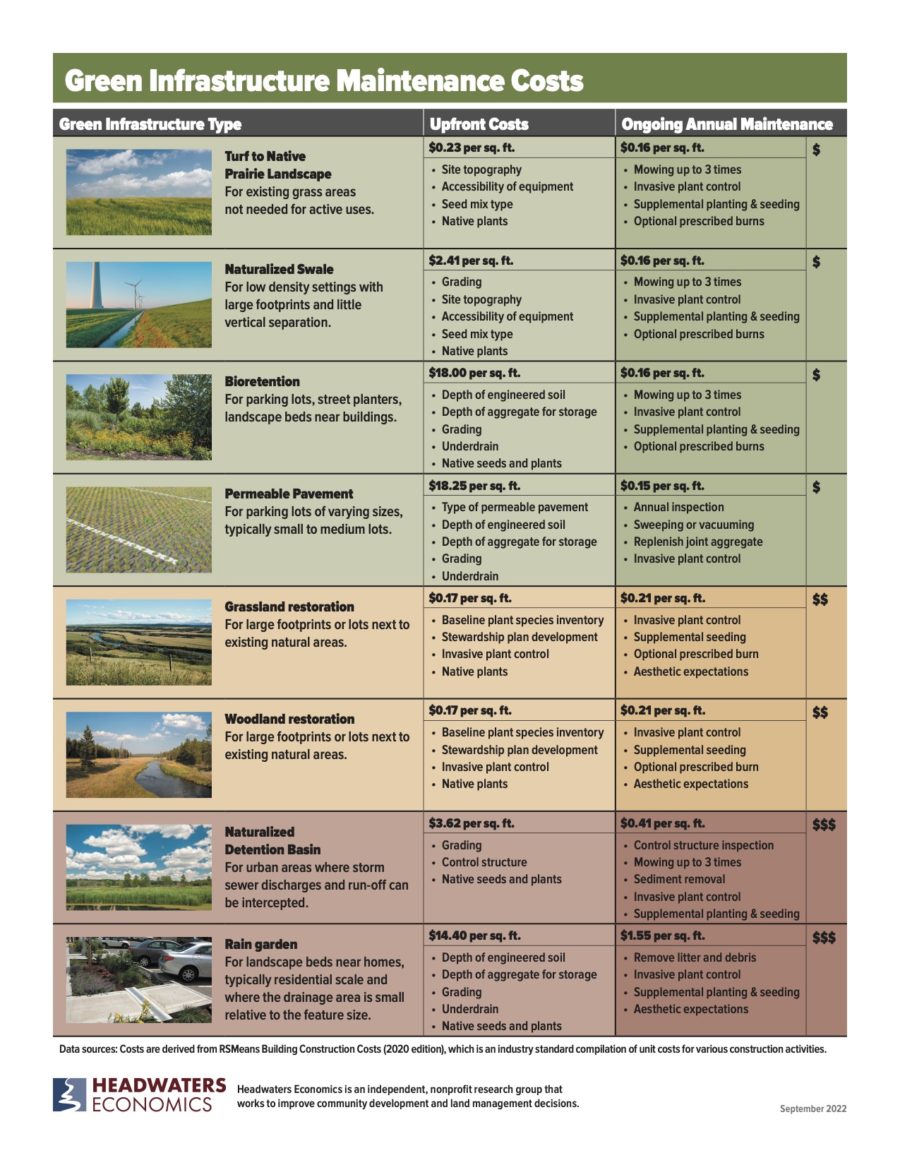

To help communities weigh strategies for reducing flood risks, we researched green infrastructure solutions with low maintenance costs. These low-cost practices may help communities use existing land assets to protect public infrastructure, private property, and lives. The cost estimates are based on industry-standard unit costs for construction in the Midwest. Geographic variability in construction costs and inflation will affect which solutions are ultimately the most cost-effective. Read more in the methods and data sources section below.

Common components of cost

Costs for Establishment

The cost of establishing green infrastructure depends on site topography and seeding styles. Sites that are relatively flat, obstacle-free, and can be easily driven over with equipment will keep costs down. Highly diverse seed mixes are generally more costly than simple seed mixes. The decision of whether to establish native plants from seed or transplants greatly impacts cost. To keep costs low, minimal areas should be established from plants. Seeding is more cost-effective for larger areas and when the landscape can be established over two to three years.

Costs for Maintenance

The maintenance of green infrastructure involves a proactive, adaptive approach. Maintenance of landscapes requires observation, monitoring, and adjusting. Ongoing course corrections can be made to increase the survival of native vegetation as it adapts to specific site conditions such as soil moisture or hydrology, available nutrients, beneficial microorganisms, herbivory, and removal of nonnative weed competition and trash.

Maintenance typically involves conducting pre-set tasks on a regular schedule, whether seasonal, monthly, or weekly. This may include mowing turf grass and removing sediment, litter, and debris from traps, spillways, or other pretreatment devices such as forebays or catchments. Maintenance will also involve regular inspections and maintenance of structures.

Aesthetic Expectations

Importantly, the level of required maintenance—and therefore cost—depends on the community’s expectations for the site’s appearance. A site classification system (“High/Medium/Low”) can prioritize maintenance and help planners determine annual budgets. Low-priority areas may be rarely seen by the public, or they may blend in with their natural surroundings. These areas are generally where a sidewalk or path does not exist and is not adjacent to public parks. Medium-priority sites are seen by the public but only on occasion, such as large public parks. High-priority sites are in highly visible and accessible areas where green infrastructure should look intentional and well kept, such as public parks, golf courses, within road rights-of-way, sidewalks and paths, and exterior views from public facilities.

Recommendations

Communities can use maintenance cost data to help evaluate potential green infrastructure projects. Understanding long-term costs can be especially important when the maintenance of green infrastructure will require interdepartmental collaboration.

Communities may also consider the following recommendations:

- Consider hybrid green-grey projects. For example, rain gardens can slow down stormwater and provide access to subsoils for water to seep into while also diverting excess water to grey infrastructure such as gutters to reduce the risk of localized flooding.

- Incentivize green infrastructure through regulations and redevelopment. Stormwater management plans, standards, and subdivision regulations can inadvertently incentivize gutters and pipes instead of green infrastructure solutions like bioswales. Regulations and ordinances can be modified to prioritize green infrastructure. Communities can also work to incorporate green infrastructure into repair, upgrade, and redevelopment projects. For individuals, local governments can incentivize and provide information to property owners and property managers on lawn and landscaping alternatives that are responsive to the regional climate and weather patterns.

- Plan for alternative funding streams for maintenance of green infrastructure. The type of skilled manual labor required to maintain green infrastructure is often different than that needed to maintain grey infrastructure. For example, green infrastructure may require annual landscaping crews on staff, whereas grey infrastructure is often maintained less frequently by contract road and construction crews. Communities need to plan for green infrastructure maintenance as an ongoing expense that requires a steady revenue stream, as opposed to planning for large capital expenditures for grey infrastructure maintenance. Programs that incentivize community monitoring of various types of green and grey infrastructure can support accounting for maintenance as a regular expense. The National Flood Insurance Program’s Community Rating System is an example of a program that incentivizes this work.

- Adapt and re-use community assets. Property prone to flooding can be a great place to install green infrastructure. Green infrastructure can help reduce flood risk from localized stormwater management to an interconnected stream-side system. In cases where local governments have acquired low-lying land via property buy-outs and restrictive covenants limit redevelopment, green infrastructure can create a park-like asset out of a neighborhood eyesore.

- Enhance wildlife habitat in public spaces and parks with green infrastructure. The diversity of native plants and improved water quality can support habitat connectivity to facilitate wildlife movement, nesting, food, shelter, and shade; increase wildlife viewing opportunities, and help reduce the urban heat island effect by lowering temperatures. Communities can use tools like Neighborhoods at Risk to identify locations where green infrastructure would help combat urban heat and mitigate flood risk for the most vulnerable populations.

Data Sources and Methods

This analysis of establishment and maintenance costs was developed for local governments to use for budget and planning purposes, specifically for municipal tools such as capital improvement planning. The cost data were compiled by Environmental Consulting & Technology (ECT), an employee-owned environmental design firm with more than 40 years of experience providing creative and responsive solutions. The estimates are based on ECT’s 40+ years of project experience, bid tabs, and the industry-standard compilation of unit costs for construction, RSMeans Building Construction Costs Data (2020 edition).

Many local factors will ultimately influence project costs. Local governments can leverage their assets (land, right-of-way, and resources in which they have agency) to reduce or eliminate costs on some line items, such as providing a location for material storage and site access. Other cost factors, such as complex permitting with state or federal agencies or removing large amounts of materials from the project site, can increase the project cost. Additionally, more frequent and intense storms and natural events have created a greater need and demand for durable building materials that can withstand severe weather, which can further impact the price of site development materials.

While this report was prepared for communities in the Midwest, the components of costs and relative costs of each practice can be shared across geographies. As a site and project are identified, a design engineer should refine the cost estimate to include adjustments for project scale, complexity, material cost, and the labor and bidding environment.

Acknowledgments

The team at Environmental Consulting & Technology (ECT), including Patrick Judd and Tom Price, contributed knowledge and technical expertise to this project.