Proposals under both the Biden and Trump Administrations have called for significant investments in critical mineral development and mining in the United States, including on public lands. This new wave of development comes at a time when the legacy of past mining booms, tens of thousands of abandoned mines, remains unresolved. When disasters occur, such as floods and wildfires, abandoned mines can release toxic contaminants, compromise water quality, and impose costly burdens on downstream communities.

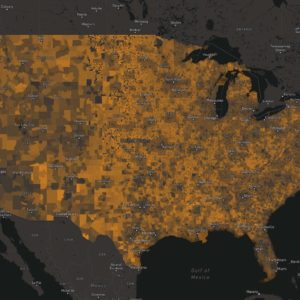

While a nationwide, comprehensive database of abandoned mines in the U.S. does not exist, the incomplete data that are available demonstrate that the scale of the threat is immense. More than 68,000 documented abandoned or inactive mines are in counties facing flood risks. California, Missouri, and Utah have the highest concentrations.

The history of abandoned mines in the U.S. demonstrates the need to thoughtfully plan for new mines and better account for disaster risk at state and federal levels, particularly during reclamation processes that can restore mined lands to a safer, more stable state. Reclaiming abandoned mines by cleaning up tailings, isolating contaminates, stabilizing soil, revegetating landscapes, and treating polluted water have been shown to prevent catastrophic environmental and economic damages. However, the large number of abandoned mines in areas with high flood risk that have not been reclaimed, in addition to the thousands of abandoned mines that have not been recorded in state or federal databases, mean that thousands of communities are facing an often overlooked, and potentially disastrous, threat.

Top 10 States with Abandoned or Inactive Mines with Flood Risk

| California | 14,100 |

| Missouri | 10,600 |

| Utah | 5,100 |

| Colorado | 4,300 |

| Washington | 3,400 |

| Oregon | 3,100 |

| Iowa | 2,500 |

| Idaho | 2,200 |

| New Mexico | 1,700 |

| Montana | 1,600 |

| Number of mines rounded to the nearest hundred. Source: USGS. | |

In this post we examine the nature of the abandoned mine threat, highlight lessons about mine reclamation from three case studies, and offer policy solutions for avoiding devastating and expensive damage from existing abandoned mines, as well as those that may result from a new wave of mining on public and private lands in the U.S.

Abandoned mines are a nationwide flood problem

Abandoned mines are areas where processing or extraction of minerals have occurred but have not been reclaimed, leaving behind waste rock piles, open pits, tailings ponds, and underground shafts. These sites are the legacy of over a century of mineral extraction, and many of the mines predate federal requirements for reclamation and clean up. When these sites are not properly reclaimed, they can degrade ecosystems, endanger public health, and create long-term economic liabilities for nearby communities and the American public.

The flood risks associated with legacy mines are often overlooked yet can be catastrophic. Heavy rainfall on these sites can cause waste rock, tailings, and heavy metals to leach into streams and waterways, polluting entire watersheds, compromising drinking water sources and wells, and compounding flood damages in downstream communities. Unvegetated slopes created by mining can increase runoff, erosion, and downstream sediment loads, making some flood events much more damaging. When abandoned mines flood, it is not uncommon for vast stretches of rivers, wetlands or other areas to become contaminated or economically unusable for decades.

Protecting communities from mine-related flood damages can be challenging. It wasn’t until the 1970s that laws began to require mine reclamation, more than a century after widespread mining was authorized on public lands. Federal agencies estimate there are 530,000 abandoned mines on public lands alone, but it is unknown how many are on private land. The incomplete records, decades of legal changes, and bankruptcies of mining companies mean abandoned mines do not have clear ownership or responsible parties that can be held liable for clean up or remediation. As a result, taxpayers are often financially on the hook for reclamation.

When a state or community does recognize the threat from nearby abandoned mines, finding funding for reclamation can be difficult. Funding availability and authority for mine cleanup varies based on mineral type, land ownership, and whether a responsible entity can be identified. State and federal agencies, including the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the National Park Service, the Department of Energy, and the Department of the Interior’s Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement all have programs to identify and remediate abandoned mines. Yet, funding levels, capacity constraints, and liability concerns have often prevented widespread reclamation, even in high-risk areas.

While the costs can be steep and the processes complicated, the benefits of reclamation are clear. Cleanup efforts reduce flood risk, protect aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, improve water quality, and safeguard human health. In some cases, reclamation projects have transformed degraded lands into places with high community value—such as parks, trails, and wildlife habitat. In others, reclamation has prevented catastrophes in biologically-rich ecosystems.

One example comes from Cooke City, Montana, where 20 years of cleanup work was completed just before a record-breaking, 500-year flood event sent water runoff over dozens of abandoned mines and into Yellowstone National Park. This upfront investment in mine reclamation paled in comparison to the post-flood clean-up costs that would have been necessary.

The 2022 Yellowstone flood: A reclamation success story

In 2022 a historic flood swept through Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding region, including the downstream communities of Gardiner, Red Lodge, and Livingston along the Yellowstone River. The flood damaged homes, businesses, and critical infrastructure, including roads and water systems. It also caused severe economic impacts, disrupting visitation to communities and businesses highly dependent on tourism.

Yet, the disaster could have been far worse. In Cooke City, a mountain gateway community to Yellowstone National Park, the New World Mining District had more than 85 gold, copper, and silver mines operating from the 1800s to the 1950s. In the decades after their abandonment rainfalls caused leftover waste rock and mine tailings to leach toxic heavy metals such as copper, lead, and arsenic into the nearby Soda Butte Creek and then into the Yellowstone River.

The impacts were severe. Mine contamination was visible throughout the landscape and river systems, with one study documenting that 80% of the trout that were exposed to Soda Butte Creek waters died. In the 1950s, a flash flood compromised the tailings impoundment and led to downstream contamination that persisted into the 1990s.

Recognizing the public safety and environmental risks, a coalition of community members, environmental organizations, and state and federal agencies launched a 20-year cleanup effort. The project included treating 110 million gallons of contaminated water, removing 500,000 tons of mine tailings, and restoring stream channels. Since 2009, the state of Montana spent nearly $25 million on the clean-up with grants from the U.S. Department of Interior and state agencies. Importantly, the project was designed to have minimal long-term operations and maintenance costs.

The reclamation work was remarkably successful. In 2018, Soda Butte Creek was removed from the EPA’s Impaired Waters List, a first for a Montana stream impacted by mining activity.

Just three years later, the 2022 Yellowstone flood tested the cleanup efforts. If not for the proactive mine reclamation work, runoff would have washed toxic hard metals into the Yellowstone River and throughout Montana’s Paradise Valley. This would have crippled the region’s economy by damaging crucial “Blue Ribbon” trout habitat, contaminating public drinking water systems, and severely limiting recreational opportunities. Bill Snoddy, with Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality’s Abandoned Mine Lands program, was quoted as saying that without the reclamation project, the 2022 flood would have caused an “ecological disaster of almost biblical proportions.”

Other examples of flooding on abandoned and legacy mines illustrate the magnitude of economic costs that could have been incurred.

Upper Clark Fork River Superfund Complex: The high cost of legacy mines

Roughly 200 miles northwest of Yellowstone National Park, the Clark Fork River watershed in western Montana illustrates how historic mining contamination, when compounded by flooding, can create environmental and economic burdens that last decades. Intensive mining in Butte and smelting in nearby Anaconda date back to the 1860s. In 1908, a major flood washed mine tailings and heavy metals, including cadmium, copper, zinc, arsenic, and lead, from Butte and Anaconda downstream to Missoula, reshaping and contaminating over 120 miles of the Upper Clark Fork River watershed. The contamination seeped into private drinking water wells, public water supplies, agricultural lands, and critical fish and wetland habitat.

The contaminated areas are now part of the Milltown Reservoir/Clark Fork River Superfund Complex, one of the geographically largest contaminated areas on the EPA’s National Priorities List. Reclamation and restoration costs are covered by a legal settlement between the State of Montana and the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO). The settlement provides critical funding for reclamation of legacy mines sites under ARCO’s ownership, but leaves out many other abandoned mines.

Montana’s Department of Environment Quality has led multiple reclamation projects related to the 1908 flood, including removing tailings, restoring the floodplain, excavating contaminated soils and draining polluted waters, at a cost of more than $600 million. Their work is scheduled to continue for decades. Despite no significant mining activity for the past 40 years, the region remains locked in costly and complex reclamation and remediation projects, stemming from the area’s vast mix of mining contamination from smelter emissions, tailings, and groundwater pollution.

Today, downstream communities such as Deer Lodge (pop. 3,035), continue to live with the consequences of the 1908 flood and subsequent pollution. The nearby Clark Fork River, rather than serving as a recreational asset, remains contaminated. At Arrowstone Park, public signs warn of arsenic in the soil and advise visitors to avoid contact with the riverbank. Remediation attempts in the 1990s failed, and the community is still working to find a solution.

Meanwhile, the threat of renewed contamination remains throughout the Upper Clark River watershed. In 2018, high water events caused arsenic and manganese to leach from legacy sediments, prompting emergency mitigation measures and illustrating its ongoing vulnerability to flood-driven pollution.

2022 Kentucky Floods: Abandoned mines make flooding worse

Frequent flooding in Kentucky illustrates another dimension of flood risk from un-reclaimed mines. Coal mining in Appalachia dates back to the 1700s, but reclamation was not required until the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act of 1977. As a result, the region has thousands of abandoned or inactive mines in need of cleanup.

Kentucky’s steep mountainous terrain is especially prone to flash flooding and landslides, compounding the risk of downstream pollution. Many communities are built along narrow valleys with steep slopes that funnel water downstream during intense rain events. Significant flood events have occurred in 2009, 2010, and 2022. The 2022 flood killed 44 people, damaged 8,408 homes, and destroyed infrastructure throughout eastern Kentucky.

Coal mining has worsened the region’s already high flood risk. According to local assessments, Kentucky has over 2,800 known abandoned and “functionally abandoned” mines, meaning mines that are legally still in operation but in practice have not operated for decades. When mountain removal and strip coal mines do not reclaim lands in a timely matter, the land is left with compacted, unvegetated land that changes how water flows over the landscape. Heavy rains cannot be absorbed, creating more intense runoff and downstream flooding.

An analysis of Kentucky’s 2009 flood event found that the peak flows increased from 77-81% due to the impacts of mining. As a result, several families impacted by the floods sued four coal mining companies and argued their business practices destroyed their homes. While the case was settled outside of court, it prompted a small but growing body of research connecting mining practices and inadequate reclamation to increased runoff and flooding. The findings demonstrate the need for reclamation to revegetate with native plants, stabilize the soil, and grade slopes to reduce runoff and erosion during heavy precipitation events. Revegetation strategies that restore the land’s natural ability to manage water and promote ecological function are better for reducing flows when compared to fast-growing revegetation strategies that do little to prevent erosion and runoff.

A fixable problem: Improving reclamation to reduce flood risk

The three case studies above are a powerful illustration of how reclamation can protect against floods, demonstrating that inaction is the more expensive choice. Yet, efforts to reclaim abandoned mines and reduce downstream flood risk face several persistent barriers. Policy priorities at state and federal levels must be adjusted to guide more effective reclamation in flood-prone areas. The following practical steps should be implemented:

1. Update and standardize abandoned mine inventories.

Standardized, up-to-date inventories across jurisdictions are essential to understanding the full scope of risk and prioritizing sites for cleanup. Yet, current inventories of abandoned mines are incomplete, outdated, and fragmented. Some states, Tribal governments, and individual federal agencies have inventories, but most of them are not standardized for comparison. Federal agencies estimate that only one in four abandoned mines are currently documented. Private lands remain a major blind spot, with no nationwide dataset available.

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, USGS was mandated to create a more comprehensive database, utilizing existing state, public land agency, and tribal databases. Funding and dedicated staff are needed to continue this effort, which is critical to understand the magnitude, timeline, and resources needed to avoid future economic losses caused by abandoned mines.

2. Establish dedicated funding for hardrock mine reclamation.

Unlike coal mines, which pay into the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Fund, hardrock mines are exempt from federal royalties and reclamation fees. This leaves abandoned hardrock sites, many of which are located in Western states, without a stable source of cleanup funding. Establishing a dedicated hardrock mine reclamation fund, managed by the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement similar to the AML fund, would give states, Tribal governments, and communities the resources to plan multi-year cleanups and address hazards before they escalate into disasters. This funding would likely have to be established by Congress.

3. Design reclamation projects to reduce flood risk, enhance ecosystems, and build community assets.

Reclamation can do more than just eliminate hazards. It can be an opportunity to reduce flood risk, improve watershed function, and create long-term community value. In many cases communities can pursue reclamation strategies that make their residents better off by developing recreation or economic revitalization opportunities. For example, in Musselshell County, Montana, the community has reclaimed a 30-acre former mine site on the Musselshell River. The county is now collaborating with state agencies, Snowy Mountain Economic Development Corporation, and nonprofit partners (such as Headwaters Economics’ FloodWise Community Assistance program) to plan and construct recreation opportunities and projects to decrease flood risk throughout the site. Federal programs can support this work by giving state and Tribal programs more autonomy to align projects with local goals, incorporate community input, and maximize co-benefits like recreation, habitat, and economic development.

4. Incorporate abandoned mines into state and local hazard mitigation planning.

Mine reclamation is often siloed from emergency management, though they have overlapping objectives in risk reduction. State and local hazard mitigation plans often do not identify the risks posed by abandoned mines. Integrating mine-related hazards into hazard mitigation plans would enable local and state governments to assess these risks alongside other hazards, prioritize projects with multiple benefits, and position and broaden the pool of potential funding sources. Emergency managers can elevate the risks of abandoned mines to the community to help build momentum for cleanup. States can support this process by providing technical guidance and hazard mapping to help local governments incorporate abandoned mine risks into their planning and mitigation strategies.

5. Plan for mine closure from the start.

While cleanup of historic mines is urgent, future mining projects must also be designed with closure and reclamation in mind. While there are better regulations for reclamation and mine closures, mines are still developed without enough planning for the end-of-life phase, or sufficient bonding, for long-term site stabilization. As mines near their end of life, owners often sell them to other, often smaller companies that are at higher risk of going bankrupt. This increases the risk of future mine abandonment and liability for taxpayers.

Modern permitting should require developers to submit clear, enforceable plans that account for long-term maintenance, water treatment, and site hydrology once a mine is closed. Closure designs should aim to reduce flood risk, minimize legacy contamination, and avoid saddling communities with future liabilities. State agencies can require and enforce timely, progressive reclamation throughout the mine’s life cycle, and require bonds or financial assurances that cover the full costs of reclamation and closure to prevent bankrupt companies from escaping cleanup duties. Better legal frameworks can ensure reclamation is still required even in the event of a bankruptcy. Improved permitting processes and better coordination with state and federal agencies can help ensure mine closure plans reflect local needs and environmental realities.

Other tools, such as community benefits agreements, can help communities meet long-term goals and proactively prepare for the end-of-life phase of a mine. Community benefits agreements are legal documents negotiated between a community coalition and a mine operator that ensures communities fully benefit from projects. They can be used to establish third-party monitoring of sites, ensure the mine is fully cleaned up when mining ends, and develop creative solutions for addressing flood risks.

Well-funded and thoughtfully designed reclamation reduces flood risk, improves water quality, and leaves lasting public benefits. As potential liabilities from new mineral extraction and flood risks mount, now is the time to ensure responsible stewardship of mined lands. Federal and state policy reforms can ensure that mine reclamation is planned and prioritized, protecting communities and the American public from future financial burdens.

Data Sources and Methods

To identify areas where legacy mining activity and flood hazards overlap, this analysis examined the abandoned or inactive mines in counties that have experienced at least one flood-related FEMA disaster declaration since 2000.

Mine data come from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Mineral Resources Data System (MRDS). This dataset provides records of mineral occurrences, past producers, and other related sites on both public and private land. The MRDS has not been updated since 2011 and has notable gaps that likely underestimate the magnitude of abandoned or inactive mines. For this analysis, we included only records located within the United States that have a development status (“Dev Stat”) of Past Producer, which is defined as mines that have “formerly closed, where the equipment or structures may have been removed or abandoned,” according to the Metadata.

Each mine was spatially assigned to a U.S. county using a geographic overlay with U.S. Census county boundaries.

County-level mine data was joined to FEMA major disaster declaration records to identify counties that experienced at least one flood-related disaster declaration from 2000 to the present and have abandoned or inactive mines. This step enables analysis of the intersection between historical mine sites and flood risk exposure.

Data limitations

Findings in this analysis likely underestimate the magnitude of abandoned mines with flood risk due to data limitations. According to the USGS, since a comprehensive national dataset of abandoned mines does not exist, “the total risks and liabilities from abandoned mine features in the United States is unknown.”

Local factors—including mine type, extreme weather, infrastructure, and local resources—also influence risk. Therefore, this analysis could over- or under-estimate risk for some counties. The analysis does not provide data for prioritizing geographically specific actions. Inclusion in the map above does not guarantee a disaster involving an abandoned mine will occur; exclusion does not imply the absence of risk.

Acknowledgements

Headwaters Economics thanks the many experts who were interviewed for this research and contributed financial data and background context, including staff from the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Sam Carlson (Clark Fork Coalition), Jonathan P. Thompson (High Country News), Kevin Zedack (Appalachian Voices), and Mark Haggerty (Center for American Progress).