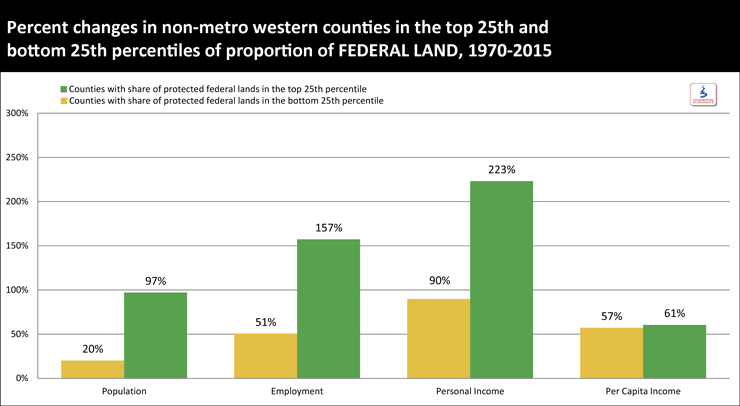

This update of research from last year finds that from the early 1970s to the early 2010s, population, employment, and personal income on average all grew significantly faster—two times faster or more—in western rural counties with the highest share of federal lands compared to counties with the lowest share of federal lands. Per capita income growth was slightly higher in counties with more federal land.

While there are exceptions to these findings–some places with little federal land are performing well and some places with significant federal land are struggling–they demonstrate significant trends across the rural West.

The study reviews the 276 non-metro counties in the 11 contiguous western states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. The counties were broken into quartile groups by share of federal land for analysis.

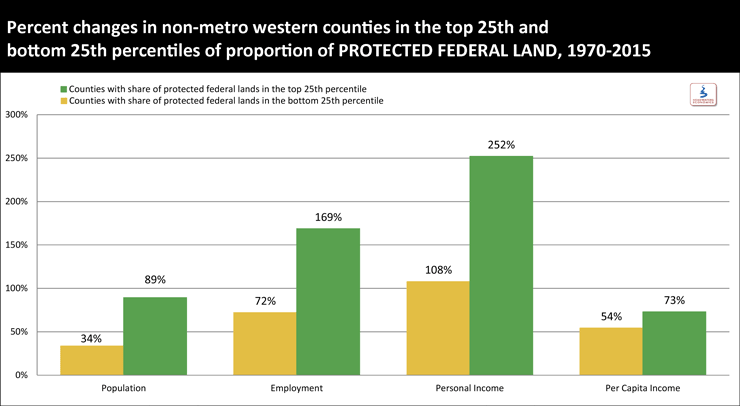

These same findings–of better economic performance in four key economic indicators–hold on average for non-metro western counties with a larger share of protected federal lands, such as National Parks, Wilderness, National Conservation Areas, National Monuments, and National Wildlife Refuges.

These findings do not represent a short-term business cycle or the influence of a single industry. They show that as the regional western economy grows during the longer-term, federal lands and protected federal lands in rural counties are associated on average with better economic performance. Details can be found in the printable version of this report.

Headwaters Economics also has compiled a number of regional reports, case studies, tools, research library, and related news articles on the value of public lands to nearby communities; along with an extensive slideshow (PDF) outlining the economic role of federal lands in today’s economy and the importance of public lands in rural development.

The Rural West and the Changing Economy

The economy of the West has changed dramatically in recent decades and rural economies in particular have been challenged in the past several decades to sustain prosperity. Some of the reasons for this include a broader transition from a commodity-based to services-based economy and the lack of access to major markets for many rural places.

Employment in non-service industries like manufacturing, farming, and forestry are holding relatively steady but have not created many net new jobs as the overall economy has expanded.

As a result, some rural and isolated areas are struggling to sustain population, rely on employment concentrated in slow growth or volatile sectors such as agriculture and oil and natural gas industries, and increasingly depend on retirement income.

Some of the differences in economic performance are a function of topography and historical land use: communities dominated by flat, arable land tend to depend more on agriculture, which has employed fewer people as it becomes increasingly efficient and automated. These also are the places with more private and less public land. Communities with land unsuitable for agriculture are more likely to have a large share of federal land, which in some places has spurred more diverse economic activity.

By comparison, service industries that employ people in a wide range of occupations—from doctors and engineers to teachers and accountants—are driving economic growth and now make up the large majority of jobs in both metro and non-metro areas.

At the same time, non-labor income, which consists largely of investment and retirement income, is the largest and fastest-growing source of personal income in the region. Non-labor income dominates money coming into both booming retirement communities and declining timber or mining towns where there is little other economic activity.

The West is one of the most urbanized regions of the country even while it has significantly more federal lands and is characterized by wide, open spaces. Across the eleven continental western states, 92 percent of westerners now live in metro counties while 8 percent live in non-metro counties. Despite this urban concentration of people and economic activity, the West is largely rural—76 percent of the landscape of the West is non-metro by county land area.

Also, the West has outpaced the rest of the nation in population, employment, and real personal income growth since 1970. But because much of this growth is happening in urban parts of the West, some rural places are being left behind.

The profound shift in how and where our economies generate value, and also jobs and income, readily can be seen at the county level using the West-Wide Economic Atlas. Detailed, local-level socioeconomic profiles are available using the Economic Profile System.

Discussion: What Next for Rural Western Counties?

The economic trends discussed above—the growth in services, relative decline of goods-producing sectors, urbanization of the West, importance of access to markets, and other factors—help to explain how the economic role of public lands in the West has shifted.

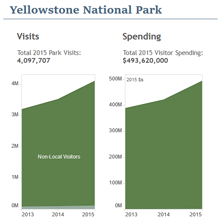

Federal lands continue to provide natural resources for commodity sectors, but also offer recreational opportunities, natural amenities, and scenic backgrounds that stimulate migration, drawing entrepreneurs and attracting a skilled workforce across a range of faster growing industries. High-performing counties with a large share of federal land generally have capitalized on federal lands in multiple ways.

Within this larger context, each region and county typically has a different economic potential, and many rural economies—across the West and the nation—face headwinds as they try to sustain portions of their commodity past while creating and attracting jobs related to the modern services economy.

While many rural counties can benefit from federal lands and natural amenities, by themselves these amenities often are not a sufficient condition for economic development. Some counties with extensive federal land have struggled, while places with little federal land have done well.

As a result, local economic strategies should be active and tailored to existing strengths and emerging competitive opportunities, including workforce skills, proximity to larger markets, and the range of uses for natural resources. Communities generally will need to invest in a mix of traditional and newer industries, education, and access to larger markets via transportation and communication infrastructure. Proximity to federal land can provide a competitive advantage to nearby communities.

Methods

This analysis includes the 276 non-metro counties in the 11 contiguous western states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Using the Census’ classification of metro and non-metro counties, non-metro counties are defined as those without a core urban area with a population of 50,000 or more. See the full methods paper for additional information.

The analysis used economic data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ Regional Economic Accounts for the years 1971 through 2015. To mitigate the effects of short-term business and commodity cycles, we calculated growth by dividing the average economic performance in 2011-2015 by the average economic performance in 1971-1975. Income data were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index.

We calculated quartiles of the proportion of county area that is federal land or protected federal land ownership using the USGS Gap Analysis Program database. The quartiles were calculated using all non-metro counties. Protected federal land is defined as lands with more permanent management restrictions such as National Parks, Wilderness, National Conservation Areas, National Monuments, and National Wildlife Refuges.

We performed several robustness checks to test our findings’ sensitivity to analytical assumptions. When the outliers with high proportions of federal lands—such as Teton County, Wyoming (Jackson Hole) and Pitkin County, Colorado (Aspen)—are removed, the results are similar: population grew five times faster, employment grew three times faster, and personal income grew twice as fast in places with the most federal land compared to places with the least. Per capita income grew slightly less (by 52% in high federal lands counties compared to 56% in low federal lands counties), although the difference is not statistically significant.

For a separate robustness check of our starting and ending years, we calculate growth as the percent change between 1970 and 2015 rather than comparing average performance at the beginning and end of the analysis period. This had no meaningful effect on the overall results.