This report finds that the West’s popular national parks, monuments, wilderness areas and other public lands offer its growing high-tech and services industries a competitive advantage.

State-Level Reports

Executive Summary

This report, “West Is Best: How Public Lands in the West Create a Competitive Economic Advantage” (4.7MB PDF) finds that the West’s popular national parks, monuments, wilderness areas and other public lands offer its growing high-tech and services industries a competitive advantage, which is a major reason why the western economy has outperformed the rest of the U.S. economy in key measures of growth–employment, population, and personal income–during the last four decades.

In addition, as the West’s economy shifts toward a knowledge-based economy, new research shows that protected federal public lands support faster rates of job growth and are correlated with higher levels of per capita income.

General findings:

- Higher-wage services industries, such as high-tech and health care, are leading the West’s job growth and diversifying the economy.

- Entrepreneurs and talented workers are choosing to work where they can enjoy outdoor recreation and natural landscapes.

- Increasingly, chambers of commerce and economic development associations in every western state are using the region’s national parks, monuments, wilderness areas and other public lands as a tool to lure companies to relocate.

- High-wage services industries also are using the West’s national parks, monuments, wilderness areas and other public lands as a tool to recruit and retain innovative, high-performing talent.

Specific points:

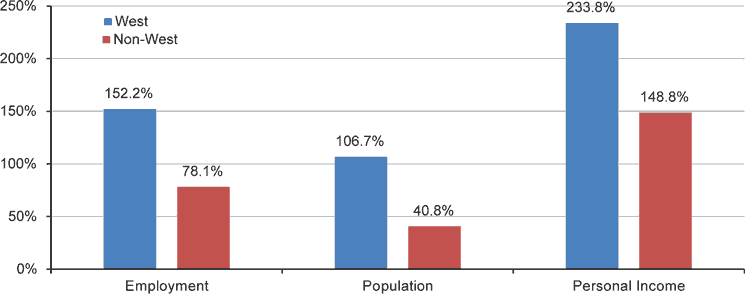

- From 1970 to 2010, the West’s employment grew by 152 percent compared to 78 percent for the rest of the country.

- This western job growth was almost entirely in services industries such as health care, real estate, high-tech, and finance and insurance, which created 19.3 million net new jobs, many of them high-paying.

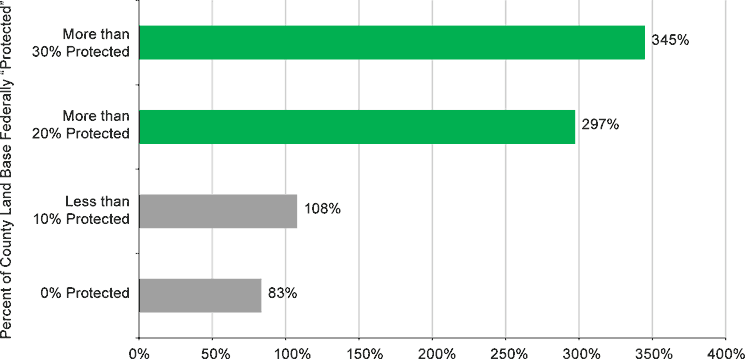

- Western non-metropolitan counties with more than 30 percent of the county’s land base in federal protected status such as national parks, monuments, wilderness, and other similar designations increased jobs by 345 percent over the last 40 years. By comparison, similar counties with no protected federal public lands increased employment by 83 percent.

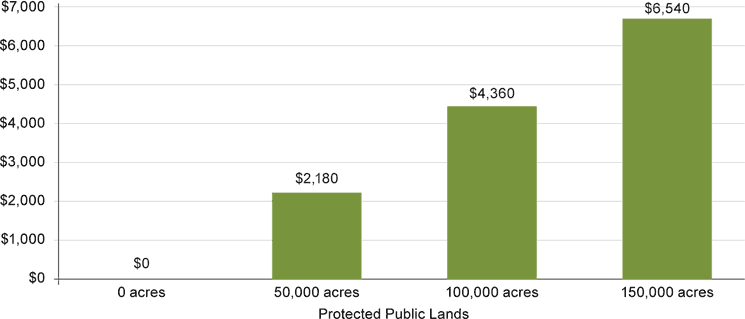

- In 2010, per capita income in western non-metropolitan counties with 100,000 acres of protected public lands is on average $4,360 higher than per capita income in similar counties with no protected public lands.

Introduction

In this report the “West” is defined as the eleven western public lands states in the continental U.S.: Arizona, Colorado, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

The western economy has outperformed the rest of U.S. economy in key measures of growth–employment, population, and personal income–during the last four decades. The region has prospered by successfully diversifying its economy to include fast-growing and higher-paying services industries–such as high-tech, finance, and health care jobs–and attracting talent and entrepreneurs who incubate tomorrow’s companies.

As the West continues to shift from a natural resource-based economy to a knowledge-based economy, the key to the region’s competitiveness is increasingly the ability to cultivate and attract innovative companies and an educated workforce. Research shows that these companies and individuals are increasingly “footloose” and are drawn to the West’s high quality of life, which includes outdoor recreational opportunities and attractive natural landscapes.

“In the ebb and flow of the global economy, states can no longer rely solely on strategies of keeping costs low and providing incentives…. Instead, states must create the right business climate that allows companies and entrepreneurs to create 21st century jobs.”1 –U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Enterprising States 2012

In the fierce global competition for business and talent today, the West has a clear competitive advantage in its public lands. The West has more federal public lands, and protected public lands such as national parks and monuments, than any other region of the country. These lands offer access to hiking, fishing, hunting, skiing, boating, and other forms of recreation, and provide a scenic backdrop to the region’s communities.

Not surprisingly, economists have found that western national parks, monuments, and other protected federal public lands support faster rates of job growth and are correlated with higher levels of per capita income.

This report reviews the West’s increasing economic diversity, the growth of the region’s modern services economy, and the economic role of public lands in the West. It examines the West as a whole, including large metropolitan areas where most economic activity takes place, as well as the non-metropolitan West where small to mid-sized communities also are successfully competing for businesses and talent, and creating new jobs by leveraging nearby public lands.

The West Outpaces the Rest of the U.S.

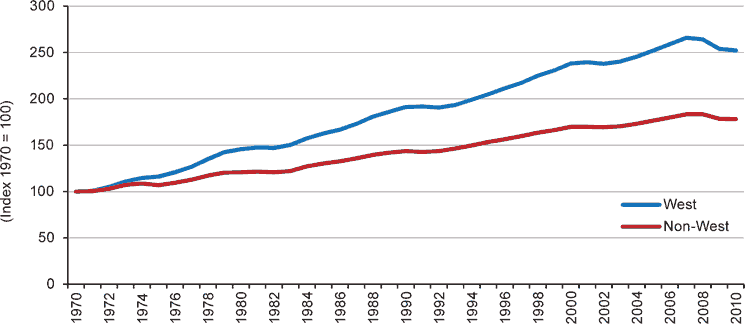

During the last four decades, the western economy outpaced the rest of nation. This can be seen in employment, where from 1970 to 2010 western jobs grew by 152 percent compared to 78 percent job growth for the rest of the country.2

We show data through 2010 because this is the latest year the U.S. Department of Commerce has reported economic data at the county level.

Figure 1: West vs. Non-West, Employment Growth, Indexed, 1970 to 2010

Population and personal income growth (adjusted for inflation) in the West also have outpaced the rest of the country. From 1970 to 2010, the West’s population grew by 107 percent compared to 41 percent for the rest of the country, and real personal income in the West grew by 234 percent compared to 149 percent for the rest of the country.3

Figure 2: West vs. Non-West, Growth Measures, 1970 to 2010

Public Lands Are Abundant in the West

To begin to understand why the West is outperforming the rest of the country, it is important to recognize two major differences. First, the West has significantly more federal public lands. Second, the West has a population that is more concentrated in urban areas. The region is also characterized by an expansive geography that is more sparsely populated than other parts of the country.

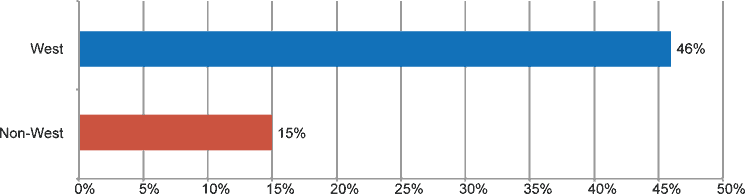

Federal public lands are a defining feature of the West. The federal government manages 355 million acres in the West, or 46 percent of all land in the region. By contrast, the federal government manages 15 percent of all land in the rest of the country.4

Figure 3: Percent Land in Federal Ownership, West vs. Non-West

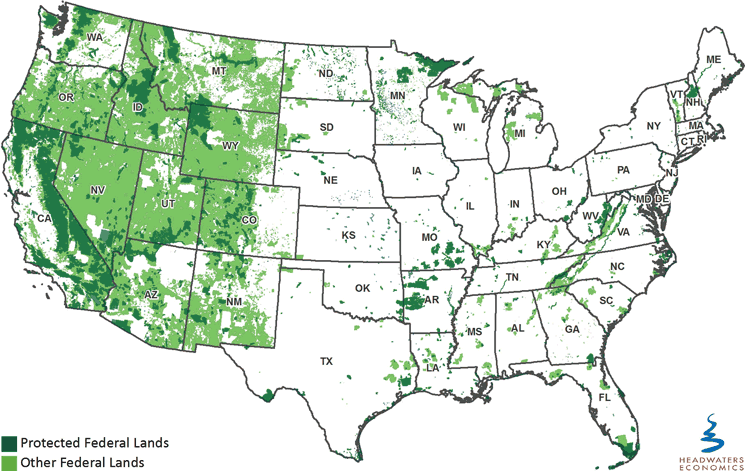

The map below shows federal public lands that are managed by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service–which together constitute the large majority of federal lands in the West. They are managed for multiple-use objectives, such as resource extraction and recreation, and also for the protection of natural, cultural and historical resources.

Multiple-use public lands are shown in light green and protected public lands in dark green. Twenty-one percent of federal public lands in the West are permanently protected as national parks, national monuments, wilderness, national wildlife refuges, and other designations.5

Map 1: Federal Lands and Protected Federal Lands, United States

The West’s population and economy are located largely in metropolitan (metro) counties. Eighty-nine percent of the population and 90 percent of the jobs in the region are found in these counties. Yet the majority of the land base in the West is covered by non-metropolitan (non-metro) counties and is characterized by smaller communities and wide-open spaces.6

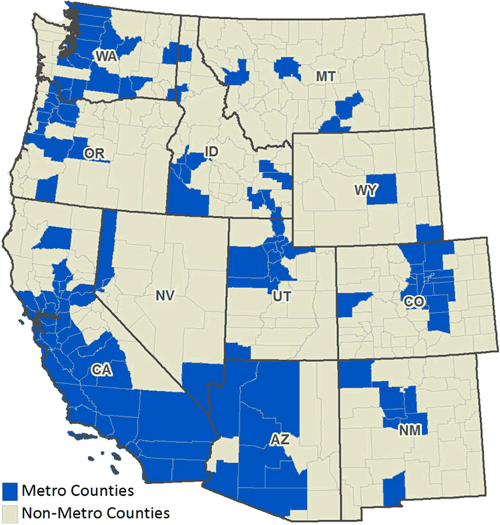

The map below shows western metro and non-metro counties. There are 128 metro counties (31% of total) and 286 non-metro counties (69% of total) in the West.

Map 2: Metro and Non-Metro Counties, The West

Public lands are important to both metro and non-metro western counties, though they are a larger share of the land base in the non-metro West. Thirty-nine percent of the land area in metro counties and 46 percent of the land in non-metro counties in the West are administered by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, or U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Historically, metro and non-metro counties had closely tied but distinct economic activities and roles.7 As we will see below, a growing number of non-metro counties are now successfully competing for higher-paying jobs in growing industries–in part by leveraging the presence of public lands to attract companies and talent–that have traditionally been found only in metro economies.

The West’s Rise Is Driven by Expanding Services Industries

The meteoric rise of the West in recent decades is largely explained by the region’s success in developing and attracting a diverse services economy. Services encompass an array of sectors ranging from low-wage industries such as accommodation and food services to high-wage industries such as professional and technical services, including architects, engineers, and computer programmers.8

Sitel, Las Cruces, NM We operate a contact center in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Sitel originally decided to open the operation here because of a favorable labor market and strong educational institutions as well as easy access to a major airport. Our initial team found the location extremely attractive. Let’s face it, Las Cruces is the jewel of the southwest–this attractive city is surrounded by accessible public lands and has incredible views of the mountains and high desert. Because of the nature of our work, we are indoors and plugged into technology most of every working day. So the ability to disconnect and get outdoors before and after work is crucial to everyone’s sense of well being. The outdoor amenities and quality of life here are a big part of what keeps us productive and how employees relate to each other–it’s often what we talk about in break areas and over lunch or before meetings. I am proud of the work-life balance we can offer in southern New Mexico. Initially, we hired people from outside the area to fill positions. Now we mainly hire regionally and have seen many advance their careers through the ranks. We are not just providing jobs; we are offering life-changing careers with advanced placement opportunities. –John Munoz, Director

We first examine the growth of services sectors in the West as a whole, which from an economic standpoint is dominated by large metro areas, followed by a look at the non-metro West. Both regions have undergone significant transformations toward a services economy in recent decades.

The West as a Whole

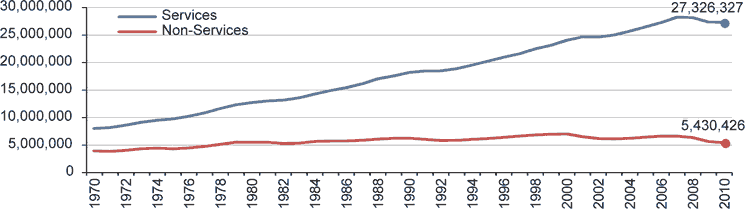

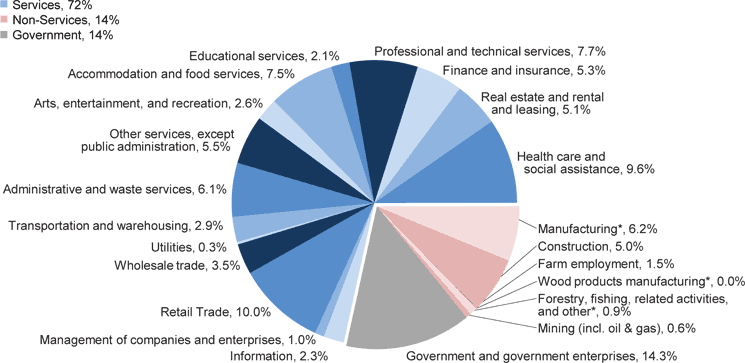

As the line graph below shows, across the West services sectors created 19.3 million net new jobs, or almost 100 percent of net new jobs in the West, during the last four decades. Non-services sectors as a whole are holding steady from an employment standpoint as the broader economy expands.9

Figure 4: Services vs. Non-Services Employment Growth, West, 1970 to 2010

To better understand services sectors, the figures below show recent growth and share of total employment at a more detailed industry level.

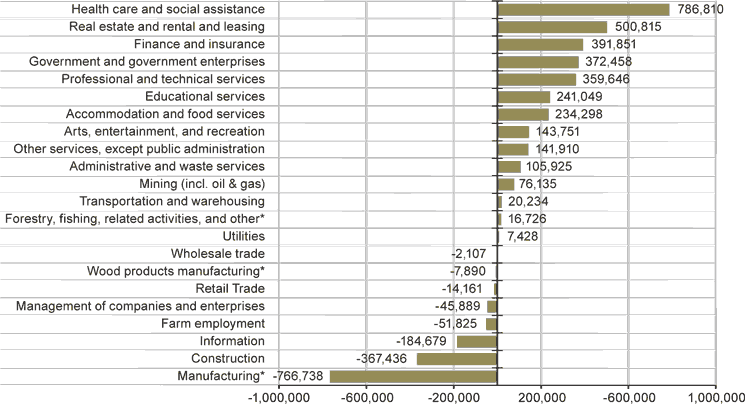

Figure 5: Change in Employment by Industry, West, 2001 to 2010

In the West, the top job creators in the last decade were all services sectors, many of them relatively high-paying: health care (+786,810 jobs), real estate (+500,815 jobs), and finance and insurance (+391,851 jobs). By contrast, non-services industries such as manufacturing (-407,192 jobs) and construction (-367,436 jobs) were the leading source of job losses in the West during the last decade.

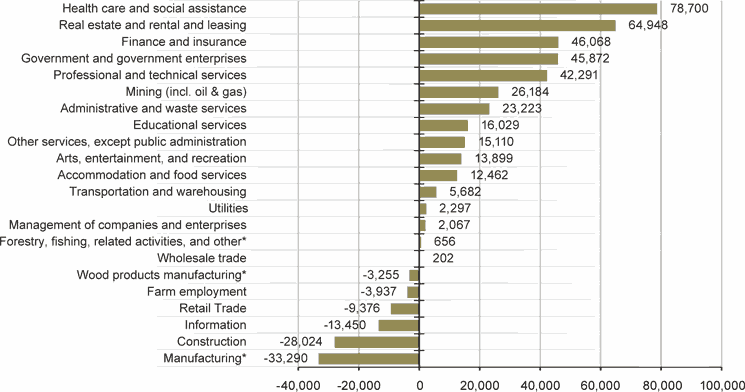

In 2010, services sectors as a whole accounted for 72 percent and non-services for 14 percent of total employment in the West. Government jobs also are important in the region and made up 14 percent of total employment in the same year.10

Figure 6: Employment by Industry Percent of Total, West, 2010

Non-Metro West

While the economies of non-metro areas in the West are smaller in scale and often face challenges related to sector diversity and access to larger markets, here too services sectors lead growth.

From 1970 to 2010, services sectors created more than two million net new jobs, or nearly 100 percent of net new job growth in the non-metro West. Non-services have been roughly flat over this same period.12

Figure 7: Services vs. Non-Services Employment Growth, Non-Metro West, 1970 to 2010

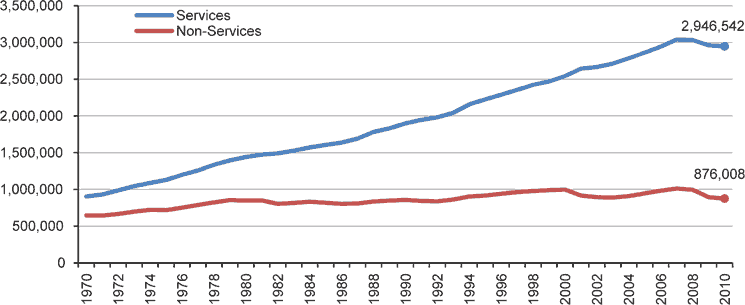

During the last decade, the leading job creators in the non-metro West were all services sectors, many of them higher-paying. In fact, they are the same industries posting top job gains in the West as a whole. Health care added 78,700 new jobs, real estate 64,948 new jobs, and finance and insurance 46,068 new jobs from 2001 to 2010.

By contrast, non-services industries such as manufacturing (-32,607 jobs) and construction (-28,025 jobs) were the leading source of job losses in the non-metro West in the last decade.

Figure 8: Change in Employment by Industry, Non-Metro West, 2001 to 2010

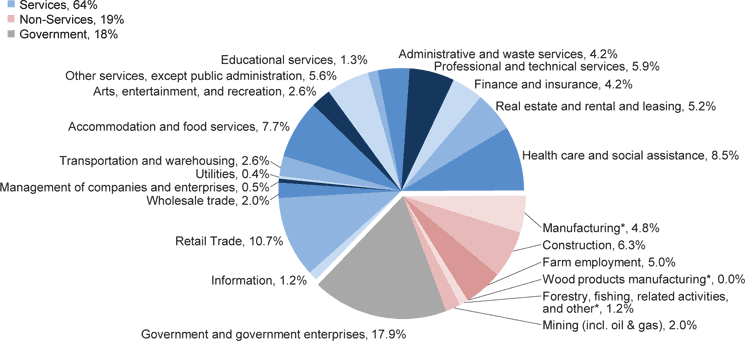

In 2010, services sectors as a whole accounted for 64 percent and non-services for 19 percent of total employment in the non-metro West. Government jobs also are important in the region and made up 18 percent of total employment in the same year.13

Figure 9: Employment by Industry Percent of Total, Non-Metro West, 2010

Services Industries Predominate in Most Western Counties

As the previous pages show, services employment is driving job growth and is now the dominant form of economic activity in the West, including the non-metro West.

Not surprisingly, services sectors are widespread across western communities and higher-paying services are a key ingredient of many local economies.

Figure 10: Number and share of western counties reliant on services and high wage service sectors, 2010

| Threshold | # of Counties | % Western Counties | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Services | ≥ 70% Total Private Jobs | 203 | 49% |

| High-Wage Services | ≥ 15% Total Private Jobs | 165 | 40% |

In 2010, services sectors were 70+ percent of total private employment in 203 of 414 western counties, or 49 percent of total. These services-reliant economies are evenly distributed between metro and non-metro counties, though they are represented in a greater share of metro counties. In 2010, 101 metro counties (79% of total metro) and 102 non-metro counties (36% of total non-metro) were significantly reliant on services sectors.

High-wage services sectors are of particular interest to communities seeking economic growth because they indicate greater success developing and attracting the higher-skill aspects of the broader services economy.

Roambi, Solana Beach, CA We work in a very competitive industry — software development for mobile platforms. You have to be creative to succeed here. You have to be a company where talented people want to work to succeed. We actively leverage our location and the outdoors to attract and retain our employees. Our engineers love the outdoors and water sports in particular. A lot of them are athletes — about 85 percent. They bring their passion for sports and competition to their work. They are also risk takers and this is a core part of our entrepreneurial culture. For our employees, taking time to get outdoors is re-energizing. It builds passion and commitment, and is critical to creativity and innovation–this is where the best work happens. It’s also a competitive edge for us since not all companies work this way. We try to integrate quality of life with the quality of work at our company. We have created a culture where our employees can pursue their passions. This leads to more successful teamwork and a more successful company. As a result of the type of company we are, we have experienced very minimal turnover in our development team in the last 5 years. This is unusual in our industry, and a great benefit because turnover is expensive and hurts productivity. –Santiago Becerra, CEO

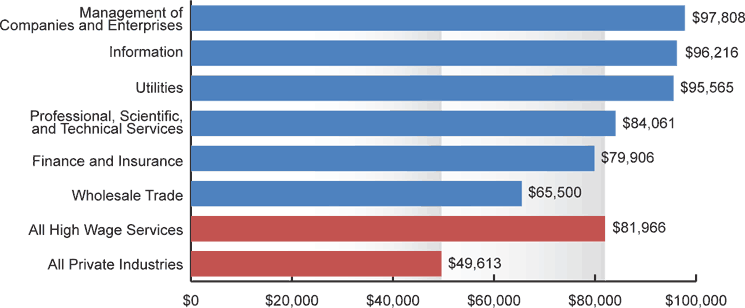

Six services sectors pay on average better than overall earnings per job for all private industries in the West. They are: information; finance and insurance; management of companies and enterprises; professional, scientific, and technical services; wholesale trade; and utilities. Other broad sectors, such as health care and social assistance, are not considered here because they mix higher- and lower-paying occupations.15

Figure 11: High-Wage Services, Average Earnings per Job, West, 201016

In 2010, average earnings per job in the West for high-wage services as a group were $81,966, compared to $49,613 for all private industries.

In 2010, high-wage services jobs accounted for 15+ percent of total private employment in 165 of 414 western counties, or 40 percent of all western counties. High-wage services are more important to metro than non-metro counties. In 2010, 88 metro counties (69% of total metro) and 77 non-metro counties (27% of total non-metro) were reliant on high-wage services at this level.17

Non-Labor Income Is a Major Driver of Growth

While services have come to define the economy of most western communities, an equally significant factor in local western economies is non-labor income.

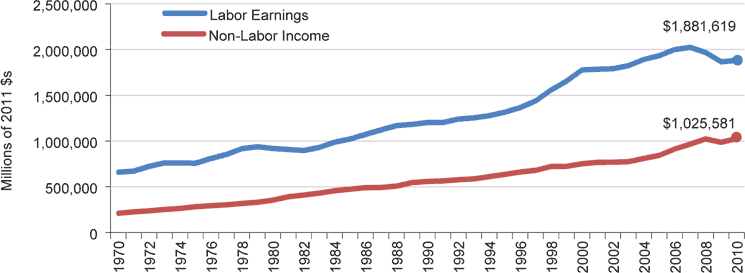

Non-labor income consists of dividends, interest, rent (money earned from investments) and government transfer payments to individuals (Social Security, Medicare, etc.).18

Both investment income and transfer payments have a significant age-related aspect, and much of their growth and significance is tied to the aging of the U.S. population, accumulated wealth, and entitlements. Only a small portion of transfer payments (6% in the West) covers things like Income Maintenance Benefits (“welfare”).19

From 1970 to 2010, non-labor income in the West grew from $211 billion to $1 trillion, in real terms, a 385 percent increase. This represents the fastest growing source of new personal income and 35 cents of every dollar of personal income in the West in 2010.20

Figure 12: Labor Earnings and Non-Labor Income Trends, West, 1970 to 2010

Non-labor income is both significant and widely distributed across the West. All 414 western counties derive 15+ percent of their total personal income from non-labor income sources. Even using a higher threshold of 30+ percent, 382 western counties, or 92 percent of total, relied significantly on non-labor income in 2010.21

Figure 13: Number and share of western counties reliant on non-labor income, 2010

| Threshold | # of Counties | % Western Counties | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Labor Income | ≥ 15% Total Personal Income | 414 | 100% |

| Non-Labor Income | ≥ 30% Total Personal Income | 382 | 92% |

Metro and non-metro western counties both depend significantly on non-labor income. In 2010, 113 metro counties (88% of total metro) and 269 non-metro counties (94% of total non-metro) derived 30+ percent of total personal income from non-labor income sources.

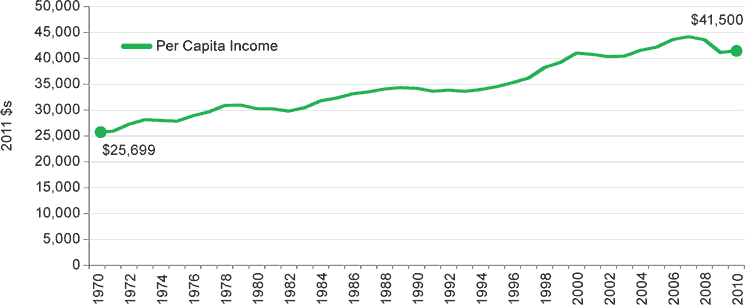

Figure 14: Per Capita Income Trends, West, 1970 to 2010

Non-labor income is doubly important: as a source of personal income that is spent in local communities across the West, and because it boosts per capita income, a widely recognized measure of economic well-being. In addition to higher-paying jobs, non-labor income contributed to raising per capita income in the West, in real terms, from $25,699 in 1970 to $41,500 in 2010, a 61 percent increase, enhancing wealth significantly in the region.22

The West Is Growing and Attracting New Residents

The ability to attract new people is essential to the vibrancy and long-term health of the West’s economy. It is even more important today as companies and individuals are freer to choose where they will locate, and competition is fierce for talented workers who are fueling some the region’s fastest growing industries.

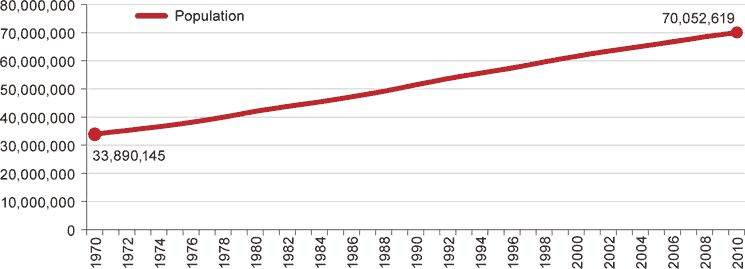

The West has the fastest-growing population of any region in the country. An expanding population and the ability to draw people are measures of the West’s attractiveness.

Figure 15: Population Trends, West, 1970 to 2010

During the last four decades the West added 36 million people, more than doubling its population. In 2010, the region’s population was more than 70 million people.23

Net migration has been an important part of the West’s ability to grow. From 2000 to 2010, the West as a whole attracted on average more than 324,000 net new people per year, contributing 39 percent of all regional population growth.24 In-migration is even more important to the non-metro West, where 49 percent of all population growth resulted from net in-migration during the same time period.

Figure 16: Number and share of western counties reliant on in-migration, 2000 to 2010

| Threshold | # of Counties | % Western Counties | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net In-Migration | ≥ 30% Net Population Growth | 208 | 50% |

| Net In-Migration | ≥ 50% Net Population Growth | 161 | 39% |

Overall, in-migration accounted for 30+ percent of all net new population growth in the last decade in 208 of 414 western counties, or 50 percent of total. During the same time period, in-migration accounted for 50+ percent of all net new population growth in 161 of 414 western counties, or 39 percent of total.

“Fully 87 percent of American voters agree that their ‘state and national parks, forests, monuments, and wildlife areas are an essential part of [their] state’s quality of life.’ A near-unanimous 96 percent of those we polled in six inner West states likewise agreed…. Seven in ten Americans and nine in ten Westerners agree that these public lands are ‘an essential part’ of their state’s economy.”26 –Pollsters David Metz and Lori Weigel

A New Competitive Advantage in the West

The economy of the West, like that of the U.S. and other industrialized economies, has shifted over time from a primary reliance on the extraction and processing of raw materials to the deployment of human skills, technology, and innovation.

In today’s economy, the West’s largest economic drivers are not directly tied to wood, gold, cattle, or other basic commodities, but rather stem from the growing value-added contributions of knowledge-based sectors across the region.

“Over the past century, the United States has shifted from an economy centered on producing physical goods to one centered on innovation and technology.” “In the twentieth century, competition was about accumulating physical capital. Today it is about attracting the best human capital.” 27 –Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs

Many of the West’s growing industries, such as entertainment, financial services, biotechnology, engineering, and software development, use few if any raw materials. The real economic value–and what is required to be competitive — lies in the knowledge-based occupations that demand specialized training and education.

In the transition from a primarily natural resource-based economy to a knowledge-based economy, the key to being competitive is the ability to cultivate and attract the most educated and talented workforce, and the businesses that employ them. Communities across the West have realized that they can do this by marketing the outdoor quality of life provided by public lands.

Waldron & Co., Seattle, WA I help enterprises recruit talent to fill key senior level leadership positions. Increasingly over the years, amenities have become more a part of the discussion with our clients and more important to candidates’ decisions about taking a job. It’s not just what the job is any longer, but where the job is that matters. Outdoor recreation is a common topic of conversation in our recruitment efforts. In the West, people make the most of the outdoors–they love to get outside and recreate. It’s part of the culture here. When I ask what the selling points are for a position, ninety percent of the time clients talk about the location. People live in the West because they want to live here. And they expect those they work with will feel the same way. –Ed Rogan, Vice President

Business Location Decisions Are Tied to Quality of Life

What do communities need to attract the best and the brightest? They require good schools and transportation infrastructure, and high-speed Internet. Increasingly, they also need a high quality of life, with clean air and water, ample recreation opportunities, scenic vistas, and other amenities that draw entrepreneurs and a skilled workforce.

This is precisely where the West excels. The region’s wide-open spaces, mountains, canyons, and other spectacular natural features set the West apart from the rest of the country. Because significant portions of these lands are public, and protected as national parks and monuments for example, they are accessible and enjoyed by the West’s residents at higher rates than in the rest of the country.28

DaVita, Inc., Denver, CO DaVita is a large and growing health care company. We recently moved to Denver, Colorado, and access to a high-quality outdoors experience was an important part of our decision. There are several powerful advantages to locating our headquarters in a community with high quality access to the outdoors. First, a lot of our best people care about the outdoors and so it was just common sense to put people in a place like Denver that provides such easy access to the outdoors. Second, when it comes to recruiting new teammates, we’ve found that the type of people who care about the outdoors are generally the ones who will help you create a healthier and more productive culture at work. And third, we believe that places that care about preserving the outdoors tend to be more community- minded. Quality of land conservation in urban and suburban environments, and in the open West, correlate almost perfectly to having the populations, electorates, and elected officials that make other healthy long-term decisions that focus on overall quality of life. When we fly people to Denver for an interview, the fact that we can so easily get them up in mountains, take them out on trails and rivers, and show them beautiful outdoor vistas makes it so much easier for us to get them interested in moving here compared to someplace without access to the outdoors. We also do a number of things directly with the outdoors to help our people become a part of our team. For example, we send teams of employees through our DaVita Outdoor Program right here in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. These outings have become an important way for us to enjoy ourselves, test our limits, and reflect on leadership and DaVita values. They change lives and improve our company’s performance. For DaVita, the outdoors is an unambiguous and fundamental competitive advantage. The kind of people with a passion for the outdoors are likely to succeeded at our company, and our company is likely to succeed when staffed by people with a passion for the outdoors. Another big pick up for us: we are able to hire a lot of talented individuals that other companies want. –Kent Thiry, CEO

A high-quality outdoor environment along with a culture of innovation gives the West a unique competitive advantage that helps explain why the region’s economy is the fastest-growing in the country. As the structure of the U.S. economy and new growth opportunities have shifted to knowledge-based occupations and industries, the factors that determine the location of companies are shifting.

Traditional location factors are relatively less important to firms in knowledge-based enterprises. Thanks to advances in transportation and communication, these companies now have far fewer constraints on where they conduct business. As “footloose” businesses, whose success is relatively independent of location, such companies are less focused on traditional cost factors and more sensitive to the preferences of CEOs and recruitment and retention factors such as access to outdoor recreation and natural landscapes.29

Quality of life variables are shifting from “would like” to “must have” location factors. A growing body of research developed over the last 30 years has documented this shift. According to a recent survey, “Quality of life consistently ranks near the top of locational criteria for high-technology, R&D labs and other facilities that are more footloose in relation to traditional cost–sensitive location factors and place a greater emphasis on attracting and retaining skilled labor.”30

For footloose firms, quality of life factors, ranging from civic pride and public health to the environment and recreation, are more important because these amenities attract businesses, and also make the recruitment and retention of employees easier and more cost effective.31 For industries where skilled labor is in high demand, quality of life factors can make the difference between hiring, or failing to hire, new workers.32

TicketPrinting.com, Bozeman, MT TicketPrinting.com started in Big Fork, Montana and then moved to Bozeman because it’s an incredible place to live and also to tap into the talent coming out of Montana State University. Our company and others are part of an emerging technology cluster that’s thriving, despite our remoteness and small population base, because of the great place this is to live and work. All of us at TicketPrinting.com are passionate about the outdoors, whether it’s fishing, hunting, hiking, or some other activity. We have a strong outdoor ethic, which has become a part of our company culture. Our quality of life is defined by our public lands and access to them. This gives us and other tech companies in Montana a distinct competitive advantage. We can recruit and retain top talent successfully within and outside the state because of the world-class landscape that surrounds us. And we benefit from a staff that is passionate about where they live and what they do. I have had customers call just to tell me that my employees are genuinely nice and want to help–that is because of where we live and work, and the kind of culture we have been able to foster here in Montana. In this sense, quality of life makes for a better company. –Lance Trebesch, CEO

While quality of life factors have grown in importance, many of today’s innovative firms also prefer locations that are close to markets, suppliers, competitors, collaborators, and a skilled workforce–what is now often referred to as an attractive business “cluster.”33

Smaller cities and rural areas that lack scale and depth in specialized areas can still compete for more innovative and growing business sectors, though they may face additional challenges attracting and retaining larger companies. There is evidence that the combination of outdoor amenities, a talented pool of workers, and an entrepreneurial context are stimulating significant economic growth in non-metro areas.34

Researchers also have pointed out that public lands in the West, along with rivers, lakes, mountains, and plentiful recreational opportunities, serve as attractants to both business owners and retirees.35 A recent review of the amenity migration research from around the world noted, “the American West is perhaps the most often-cited example of a region experiencing high rates of population growth related to amenity migration.”36

Protected Public Lands Are an Economic Advantage

A large and growing body of research has analyzed the economic role of federal public lands and more specifically the economic role of protected federal public lands. The research shows that communities and counties with protected federal public lands generally outperform those without public lands in economic performance measures.37

In 2011, more than 100 U.S. economists and related academics–including three Nobel Laureates–signed a letter urging the President to “create jobs and support businesses by investing in our public lands infrastructure and establishing new protected areas such as parks, wilderness, and monuments.” The letter states that federal protected public lands are essential to the West’s economic future, attracting innovative companies and workers, and contributing a vital component of the region’s competitive advantage.38 –Economist Letter on Value of Public Lands

Recent research by Headwaters Economics found that for the non-metro West there are important employment and personal income benefits associated with the presence in a county of protected federal public lands.

From 1970 to 2010, western non-metro counties with more than 30 percent of the county’s land base in federal protected status increased jobs by 345 percent. As the share of federal lands in protected status goes down, the rate of job growth declines as well. Non-metro counties with no protected federal land increased jobs by 83 percent.39

Figure 17: Percent Change in Employment, Non-Metro West, 1970 to 2010

“Small business owners believe protecting public lands would positively impact small business opportunities, local job growth, state economies and more: 65 percent of owners believe designating new national parks and monuments would enhance local jobs and the economy… and 52 percent agree it would help their state attract and retain new business and entrepreneurs.” 40 –Small Business Majority Poll Conducted in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico

There is also evidence that people are better off economically when they live near protected public lands. In addition to employment benefits, there are personal income rewards–in particular higher per capita income.

Looking at the West’s 286 non-metro-counties, a published statistical analysis found a meaningful relationship between the amount of protected public land and higher per capita income levels in 2010.

The effect protected federal lands have on per capita income can be most easily described in this way: on average, western non-metro counties have a per capita income that is $436 higher for every 10,000 acres of protected federal lands within their boundaries.

Figure 18: Avg. Increase in Per Capita Income from Protected Public Lands, Non-Metro West, 2010

The chart above shows four scenarios, ranging from 0 to 150,000 acres of protected public lands in non-metro western counties. The increase in per capita income explained by protected public lands ranges from $2,180 to $6,540. For example, a non-metro western county with 100,000 acres of protected public lands will have on average a per capita income that is $4,360 higher than a county with no protected public lands. To put this premium in perspective, the average per capita income for all non-metro western counties was $34,870 in 2010.42

Our research and that of others clearly show that protected public lands are a competitive economic advantage in the West, supporting faster rates of job growth and higher levels of per capita income. These benefits should increase as the region, including non-metro counties, continues to shift toward a knowledge-based economy. This raises the important question of what federal, state, and private policies and investments will maximize the value of protected public lands for western businesses and communities.

References

- 1. National Chamber Foundation, Executive Summary, http://ncf.uschamber.com/library/enterprising-states ↑

- 2. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA30. ↑

- 3. Ibid. ↑

- 4. AZ Land Resources Information System, 2009; MT Natural Heritage Program, 2008; Conservation Biology Institute, 2008 (for CA); Conservation Biology Institute, 2006 (for remaining states). ↑

- 5. Protected Federal Lands: We adopted the definition of “protected public lands” from: Rasker, R., P.H. Gude, J.A. Gude, and J. van den Noort. 2009. The economic importance of air travel in high-amenity rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies 25: 343–353. Here specific federal land designations of the National Park Service (NPS), the Forest Service (FS), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), or the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) were considered protected. These designations are: National Parks and Preserves (NPS), Wilderness (NPS, FWS, FS, BLM), National Conservation Areas (BLM), National Monuments (NPS, FS, BLM), National Recreation Areas (NPS, FS, BLM), National Wild and Scenic Rivers (NPS, FS, BLM), Waterfowl Production Areas (FWS), Wildlife Management Areas (FWS), Research Natural Areas (FS, BLM), Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (BLM), and National Wildlife Refuges (FWS). Lands administered by other federal agencies (including the Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation, other Department of Agriculture, Department of Defense, Department of Energy, and Department of Transportation) were not included, nor were state, local, or private lands. This definition of protected public lands attempts to include areas that have a higher level of managerial and commercial use restrictions than other federal lands and a less changeable status than other designations (for example, Wilderness Study Areas and Inventoried Roadless Areas). ↑Other Federal Lands: NPS, FS, BLM, FWS lands with designations other than those listed above.

- 6. Office of Management and Budget. 2009. Update of Statistical Area Definitions and Guidance on Their Uses (OMB Bulletin No. 10-02). Washington, D.C. OMB defines metropolitan counties as having at least one urbanized area of 50,000 or more in population. Non-metropolitan counties are all other counties. ↑

- 7. See, for example, Cronon, William. Nature’s metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. WW Norton & Company, 1992. ↑

- 8. For details on services industries, see North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) definitions, available here: http://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/sssd/naics/naicsrch?chart=2007 ↑

- 9. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA25 and CA25N. ↑

- 10. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA25N. ↑

- 11. Some industry categories have been modified from the original source to better illustrate employment in sub-sectors that are important to the western economy. The asterisks in these charts indicate the following. Wood Products Manufacturing is a sub-set of total Manufacturing and consists of the wood product (NAICS 511) and paper (NAICS 537) manufacturing sectors. The Bureau of Economic Analysis does not report employment at this NAICS level (i.e., the 3-digit level), but does provide personal income at this level. To estimate employment for these sectors at the 3-digit level, we calculated a ratio consisting of personal income earned in these sectors divided by personal income earned in all manufacturing. We multiplied this ratio by total manufacturing employment to estimate the number of jobs in wood products and paper manufacturing. Manufacturing consists of total manufacturing minus Woods Products Manufacturing. Forestry is part of Forestry, Fishing, Related Activities, and Other and consists of the non-manufacturing components of the timber industry, such as growing and harvesting. ↑

- 12. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA25 and CA25N. ↑

- 13. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA25N. Because this employment aggregation consists of county-level data, some underlying values at the industry level have been withheld by the U.S. Department of Commerce in accordance with federal data reporting guidelines and totals do not add to 100%. ↑

- 14. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA25N. ↑

- 15. The 2-digit NAICS codes for high-wage services used in this report are: Information (51); Finance and Insurance (52); Management of Companies and Enterprises (55); Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services (54); Wholesale Trade (42); and Utilities (22). ↑

- 16. See previous reference for NAICS codes. Average wage data are from: U.S. Department of Labor. 2012. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Washington, D.C. ↑

- 17. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA25N. ↑

- 18. For details on non-labor, see: https://headwaterseconomics.org/economic-development/trends-performance/non-labor/ ↑

- 19. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Tables CA35. ↑

- 20. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA30. ↑

- 21. Ibid. ↑

- 22. Ibid. ↑

- 23. Ibid. ↑

- 24. The difference between in-migration to an area and out-migration from the same area. ↑

- 25. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Census Bureau, Population Division, Washington, D.C. ↑

- 26. David Metz (Fairbank, Maslin, Maullin, Metz & Associates) and Lori Weigel (Public Opinion Strategies), Government does a good job of protecting our natural history, 2012, available at: http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/energy-a-environment/259763-government-does-a-good-job-of-protecting-our-natural-history ↑

- 27. Moretti, Enrico. The New Geography of Jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012. Pp. 10, 66. ↑

- 28. See, for example, Outdoor Foundation, Outdoor Recreation Participation Report 2012, available at: http://www.outdoorindustry.org/images/researchfiles/OIA_OutdoorRecreationParticipationReport2012.pdf?170 ↑

- 29. Gottlieb, P. (1994). “Amenities as Economic Development Tools: Is There Enough Evidence?” Economic Development Quarterly, 8: 270–285. ↑

- 30. Slavesen, David, and Henry Renski, The Importance of Quality of Life in the Location Decisions of New Economy Firms. January 2003. Produced by the Center for Urban and Regional Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. Page 30. ↑

- 31. Haug, P. (1991). “The Location Decisions and Operations of High Technology Organizations in Washington State.” Regional Studies 25(6): 525–541. ↑

- 32. Lyne, J. (1991). “U.S. Work-Force Woes Limiting Many Corporate Facility Location Choices” Site Selection Handbook, 36 (August) 722–728. ↑

- 33. For an informative discussion of economic clusters, see: Rosenfeld, Stuart, A. Just Clusters: Economic Development Strategies that Reach More People and Places. 2002. Regional Technology Strategy, Inc. Available at: www.rtsinc.org ↑

- 34. See, for example, McGranahan, David A., Timothy R. Wojan, Dayton M. Lambert, “The rural growth trifecta: outdoor amenities, creative class and entrepreneurial context,” Journal of Economic Geography. May 17, 2010. Available at: http://joeg.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/05/12/jeg.lbq007.full?sid=6d1911a5-28ea-4aae-8cec-43693028f42b#fn-12 ↑

- 35. Winkler R., D.R. Field, A.E. Lulogg, R.S. Krannich and T. Williams 2007. “Social Landscapes of the Inter-Mountain West: a Comparison of ‘Old West’ and ‘New West’ communities.” Rural Sociology 72 (3): 478-501. ↑

- 36. Gosnell, H. and J. Abrams. 2009. “Amenity Migration: Diverse Conceptualizations of Drivers, Socioeconomic Dimensions, and Emerging Challenges.” GeoJournal. Published online 8 July 2009. Rudzitis, G. and H.E. Johansen. 1989. “Migration into Western Wilderness Counties: Causes and Consequences.” Western Wildlands. Spring, Pages 19-23. Rudzitis, G. 1999. “Amenities Increasingly Draw People to the Rural West.” Rural Development Perspectives. 14(2), 9–13. Rudzitis, G. 1993. “Nonmetropolitan Geography: Migration, Sense of Place, and the American West.” Urban Geography. Vol. 14(6): 574-585. ↑

- 37. For resources on this topic, see: https://headwaterseconomics.org/land/reports/protected-lands-value/ ↑

- 38. For a copy of the full letter to the President, see: https://headwaterseconomics.org/public-lands/protected-lands/economists-president-public-lands/ ↑

- 39. See above references for protected public lands and metro/non-metro definitions. Employment data are from: U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA30. ↑

- 40. Small Business Majority. 2012. Polling results available at: http://smallbusinessmajority.org ↑

- 41. See “The Effect of Protected Federal Lands on Economic Prosperity in the Non-Metropolitan West,” available at:https://headwaterseconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/ProtectedPublicLands_Manuscript_2012.pdf. ↑

- 42. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Regional Economic Information System, Washington, D.C. Table CA30. ↑