Wildfire risk modeling is a vital tool for disaster preparedness and response. For decades, scientists have leveraged federal data to develop sophisticated models that predict how fire spreads through forests and grasslands, helping fire departments, land managers, and policymakers prepare for and manage wildfires.

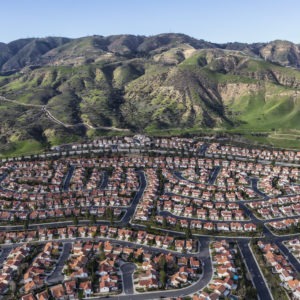

But as wildfire risks have transitioned from the forests and grasslands into communities, so must our models. Recent disasters in Lahaina, Hawaii, and Los Angeles, California, demonstrate how wildfires can spread rapidly through neighborhoods, jumping from home to home in ways that differ from fires in natural vegetation. The intense heat, embers, and debris generated by burning structures, vehicles, and infrastructure are driven by local factors that have not been captured in most wildfire risk models. The complexity of integrating building materials, housing density, fuel continuity between structures, and neighborhood layouts presents a new challenge.

Many wildfire modelers are actively working to incorporate these built-environment factors into next-generation tools. Still, wildfire models primarily reflect fire behavior in natural vegetation and do not yet fully capture how fire spreads and propagates through neighborhoods. This gap limits the ability of communities to make informed decisions about mitigation, building standards, and risk planning.

Headwaters Economics, in partnership with Pyrologix (a Vibrant Planet company) and the U.S. Fire Administration, analyzed the state of wildfire risk modeling to identify opportunities for improvement. The two-part report includes a detailed inventory of existing wildfire risk indices (Part 1) and expert interviews to highlight solutions (Part 2).

Promising new approaches and opportunities for wildfire risk modeling

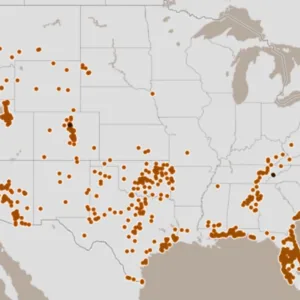

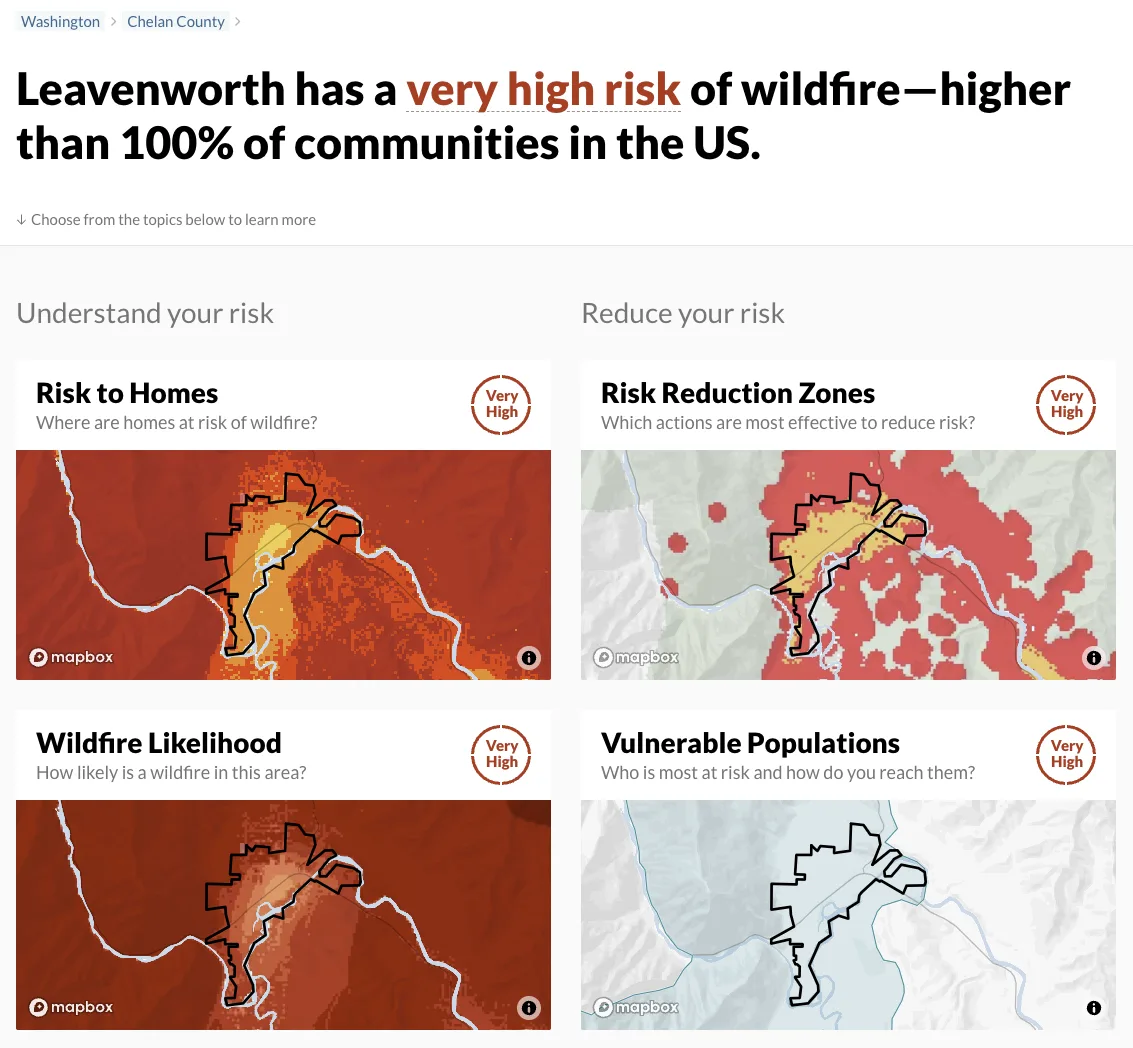

Research results show that current models face a tradeoff: some can predict outcomes for broad geographies like states or the whole nation, but lack precision about fire behavior in smaller areas such as neighborhoods, especially when it comes to structure-to-structure spread. Conversely, models that have more local precision are difficult to scale up to larger geographies. Several promising approaches supported by federal agencies—including those led by the USDA Forest Service (Wildfire Risk to Communities) and FEMA’s U.S. Fire Administration (the National Risk Index)—are making strides toward balancing the need for scalability and modeling wildfire spread into the built environment. Ongoing improvements can further integrate information about the built environment, validate the models, and make models accessible for decision-makers.

Despite imperfections and ongoing challenges, current wildfire risk models have accurately identified communities that experienced recent urban wildfire disasters. These models are an essential tool for recognizing the most at-risk communities. When combined with local knowledge and on-the-ground data, they help target prevention efforts and resource allocation to reduce wildfire impacts effectively.

Interviews with dozens of experts point to several key needs to advance the field of wildfire risk modeling:

- Cross-discipline, cross-agency coordination. A central coordinating body is needed to manage model development, direct funding, and ensure collaboration across all disciplines in wildfire response.

- Improved datasets. Researchers need better data that capture building and parcel-level details, ember propagation and transport, and the impacts of mitigation activities on fire behavior. These data can be developed through tools like remote sensing, home inspections, and crowdsourcing.

- Enhanced transparency and validation. Current models of fire among structures must be refined before they can work in real-world applications. Open comparison and critique among researchers using publicly available information will make these models stronger.

- Clarified language and standards. Models that are useful for one discipline, such as fire suppression, may not be useful for another, such as long-term mitigation planning. Clarity is needed in defining problems, scenarios, and the needs of various users to ensure models are aligned with real-world applications.

- Actionable insights. Improved models must offer pathways for behavioral change, such as home hardening, creating defensible space, and implementing regulations. Modeling advancements should proceed alongside practical, on-the-ground risk-reduction efforts.

Without these advances, communities will continue to make high-stakes decisions about where to build, how to harden homes, and how to insure property based on incomplete or outdated information.

Open collaboration is key to developing better wildfire tools

Addressing the wildfire crisis will require building better wildfire risk models: Models that incorporate structure-to-structure ignition, are validated against a wider range of scenarios, and use high-quality, accessible data.

Unfortunately, a large amount of data is not widely accessible. Insurance companies have developed their own proprietary risk models to set rates and address state regulatory issues, but these data will likely be unavailable to researchers, policymakers and the public. This includes state and local governments that need accurate, open risk maps to inform adoption of building codes, create programs to help homeowners retrofit existing structures, and align land use policy with known wildfire hazards.

To develop reliable risk maps that are accessible to a wide range of stakeholders open collaboration will be critical. The comparison and verification of existing models can be improved with publicly available benchmark datasets, including pre-fire building characteristics and post-fire outcomes. This work will require leadership and coordination across agencies, sectors, and disciplines. The federal government has an important role to play in bringing together policymakers, scientists, engineers, community and business leaders to close the gap between what we know about wildfire and how we prepare for it.

With a shared strategy it is possible to unite research efforts and greatly improve our understanding of how fires behave, and ultimately shift from reacting to wildfire disasters toward proactively protecting lives, property, and economic stability.

Acknowledgements

Matthew Thompson, Ph.D., and Bryce Young of Pyrologix, a Vibrant Planet Company, contributed knowledge and expertise to this research. This project was conducted through a partnership with the U.S. Fire Administration.