Americans love farms and ranches for all kinds of reasons. Agriculture provides not only food, but also wildlife habitat, scenery, and a sense of place that enriches those of us fortunate to live in the rural West.

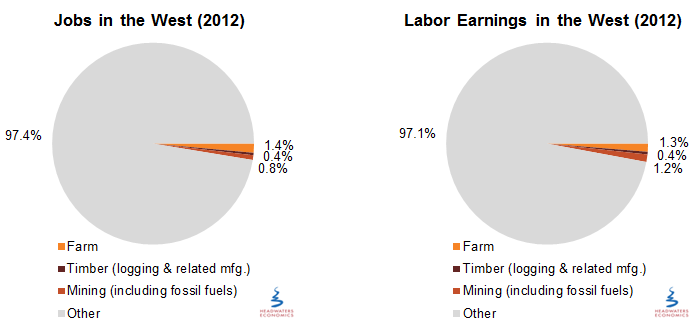

So while agriculture often serves as a draw for tourists, retirees, workers, and entrepreneurs who prefer to live near cows and wheat farms rather than in a congested city, overall–using U.S. Department of Commerce statistics–less than five percent of all jobs in Montana are on farms and ranches. Across the West as a whole it is even smaller, less than two percent.

Could it be that farm and ranch jobs create a huge multiplier effect that stretches every farm job to 20 other jobs? A more likely explanation is that politicians make these claims because it matches people’s popular perception. But public policy based on perception does little to help us prepare for today’s fast-moving, competitive global economy.

A quick scan of the West-Wide Economic Atlas we created shows a compelling story of today’s dramatic realities at the county and state level.

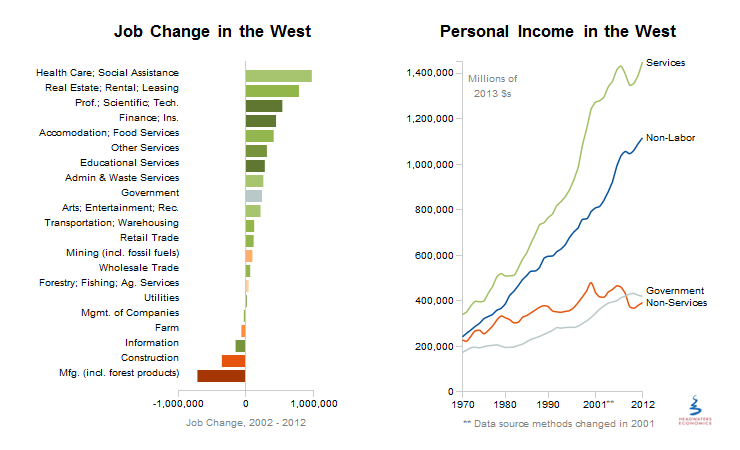

In the West, more than 70 percent of jobs are in service industries. In the last decade, the biggest contributors to new jobs have been in health care; real estate; professional, scientific, and technical services; finance; and insurance.

The race is on among communities to create the setting—through telecommunications, airports, education, and a high quality of life—to attract the higher wage components of the service sector.

Another shock to some may be that after services, the second largest driving force in the economy is non-labor income. Made up of age-related payments–retirement, Social Security, and medical payments–and investment income, these forms of personal income are now 41 percent of all personal income in western counties. And, non-labor income accounts for 60 of net new growth in personal income in the West in the last decade.

To put this in perspective, in Montana retirement income alone is now twice the size of the combined income from people employed in agriculture, oil and gas development, mining and timber.

Instead of repeating myths, our leaders should be wrestling with questions about how to educate our kids so they can be competitive in a technologically advanced, knowledge-based global service economy. Do we have the telecommunications and transportation infrastructure to trade efficiently with clients around the world? And, if reducing the size of federal budget means changes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, what multiplier effects will that have on our communities?

These are the big-picture questions where we need better leadership.