Rural West Economy in Context

The West is more than half public land, but multiple jurisdictions and private land ownership create a highly fragmented landscape. Different mandates among land managers creates competing interests, affecting the opportunities and role of public lands in local economies. A legacy of natural resource extraction, coupled with a changing economy, can make these competing interests difficult for many communities to navigate today.

Since the Great Recession, the U.S. economy is doing well. In particular, the economy in the West—and even more the Pacific Northwest—is growing rapidly. But the nature of economic growth in the West is different today, with two key changes.

First, the economy has shifted away from manufacturing to services. Especially in the Pacific Northwest, high-wage innovation sectors have driven growth. Secondly, more growth is from non-labor income—investments, age-related payments (e.g., Medicare and Social Security), and hardship payments (e.g., Medicaid and Unemployment). Rural counties rely disproportionately on non-labor income.

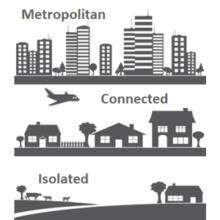

Of the growth in services, most jobs are in cities. In fact, just three cities in the Pacific Northwest are responsible for 73% of all new jobs in the region: Seattle, Portland, and Boise. On the other hand, 69% of rural counties have not yet recovered the jobs lost in the Great Recession. But this lag is also uneven. Rural, nonmetro communities connected to the major markets and population centers of metropolitan areas are performing better than their isolated counterparts.

Economic and Fiscal Change

In rural communities, changes in markets and automation have resulted in increases in productivity, but this no longer translates into more jobs. This is true across manufacturing and natural resource sectors, including timber.

Half of all nonmetro counties with high worker productivity are losing population. Today, commodity production will no long provide the value proposition it once did for rural places, and value growth does not necessarily translate into economic opportunity.

External factors compound the challenges facing rural communities, constraining the autonomy and authority of counties to build, save, and diversify revenue for reinvestment in the community. For example, timber counties receive federal payments from revenue-sharing programs, driving down local property tax levies. Counties are required to spend the funds annually, and so are unable to build a reserve. The unpredictable nature of revenue-sharing programs has exacerbated fiscal crises, leaving some counties unable to diversify into other growth areas.

Building resilience in rural and isolated communities requires new models of collaboration.

Headwaters Economics’ Mark Haggerty gave this presentation at Our America’s Rural Opportunity. The event was co-sponsored by the Rural Development Innovation Group, the Rural Voices for Conservation Coalition, Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group, and Mark O. Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University with support from the U.S. Forest Service.