The rural West today provides essential food, energy, water and economic benefits; while playing a significant role in local, state, and federal politics. The region’s social and economic outlook, however, is mixed and many western rural communities are struggling.

The share of rural Americans has been declining more than a century, and 1920 was the first census that found more Americans living in cities than rural areas. Today, roughly 85 percent of Americans live in urban settings with just 15 percent in rural areas, though the rural population covers 72 percent of the nation’s land.

Economic activity is concentrated in more densely populated counties. In Washington State, for example, just two counties contain nearly half of the state’s total employment; and just two counties in Utah make up 61 percent of the state’s employment.

Lands: Rural Areas Are Essential for Our Food, Energy, Water, and Economy

As a recent report noted: “Rural America is important to all Americans because it is a primary source for inexpensive and safe food, affordable energy, clean drinking water and accessible outdoor recreation.”

Indeed, today Americans spend less of their income on food than any other developed nation, and the rural West’s wide variety of agricultural products—whether beef, grain, or apples—play an important role in both domestic consumption and a large export market.

The production of other commodities such as timber and energy also is important in the rural West. Wyoming, for example, is the nation’s leading producer of coal, and it mines a significant amount of oil and natural gas—while Oregon is the leading timber producer in the country.

National Forests provide 33 percent of the West’s water, with a high of 86 percent in Washington State. Almost all western cities such as Denver and Portland receive a significant portion of their water supply from rural areas.

Rural lands also will play an increasingly important role adapting to climate change; whether it is continuing to provide needed drinking water to regions experiencing less rainfall or providing “refuge areas” for flora and fauna to survive altered climate patterns.

In addition, the wildlife, vistas, and scenery of the rural West support a growing outdoor recreation economy, supporting 1.9 million jobs in the West and tens of billions of dollars in expenditures.

These lands in non-metro western counties can be an important economic asset that extends beyond tourism and recreation to attract people and businesses. Rural western counties with a higher share of federal lands, for example, perform better economically on average than similar counties with the lowest share of federal lands.

Politics: Rural Western Voters Retain Significant Political Power

Rural areas have long exerted a strong political influence in most western states—whether at the county, state, or federal level. And while many non-metro areas have seen a loss of state or federal lawmakers compared to several generations ago, rural political power remains relatively strong in states such as Montana or Nevada.

Several reasons explain why rural residents’ political power is greater than their small share of the overall population.

One important factor is partisanship: rural voters have become reliably Republican. As the intensification of partisanship continues—rural counties became more red, urban counties more blue in 2016 compared to 2012—the Republican domination of many state legislatures and governorships allows rural areas to maintain their influence. Rural voters, by playing a major role in the governing political party, need only to influence that ruling coalition to impact politics and policies rather than influence a county or state’s entire population.

Another rural political advantage is age. Rural areas are disproportionately older than the country and these voters turn out in much higher numbers than other Americans, especially in non-presidential, local, or off-year elections.

At the local level, county governments are the most important political and policy decision-makers. Small towns within counties often are not incorporated or constitute a small portion of a county’s voters. Thus, rural voters usually can control fiscal, growth, and other policies.

While redistricting slowly is reducing rural influence at the state level, rural areas often retain tremendous clout in the growing political contests between cities and state governments, where state governments often are a proxy for rural voters and interests.

Rural representatives also often share similar agendas and goals, making them more efficient in pursuing goals and objectives. By comparison, one study showed that cities, despite their size, often have failed to accomplish legislative agendas partly because of the complexity and different priorities of urban voters.

Several exceptions to rural power in the West, at the state level, certainly exist. A handful or urban counties in Washington and Oregon, for example, are known for outvoting and controlling the legislatures in those states. As a reaction, in states where rural areas no longer have clear power—California, Colorado or Washington—rural areas have toyed with the idea of seceding to form their own state.

Rural political influence also remains strong at the federal level. In the House of Representatives, the concentration of Democrats in urban areas—along with a number of smaller, rural states with a sole Representative—helps Republicans hold a majority of seats. Democratic voters, by comparison, are inefficiently distributed.

For its part, the rural bias of the United States Senate actually has grown over time, and a recent academic study showed that the minimum share of total population needed to control the Senate has shrunk from 30 percent in the early 1800s to only 17 percent today. The study authors note a dramatic example: California, largely urban with 32 million citizens, has the same Senate clout as Wyoming’s 480,000 residents.

Rural advantages also are pronounced in the Electoral College. To continue the above California versus Wyoming example, each elector in California represents roughly 715,000 people, compared to fewer than 200,000 people per elector in Wyoming.

Perhaps because of this leverage, rural areas largely have protected their share of government funding. Many state and federal programs, for example, continue to contain funding minimums for assistance to rural areas. In addition, because many funding formulas were created in earlier eras when rural populations were relatively larger, rural regions often continue to receive roughly the same spending per person as urban or suburban areas.

People: Many Rural Western Communities Are Struggling

The economic challenges facing rural areas have been well documented. While the challenges facing rural regions often are difficult, some rural areas are stable or even thriving. Today, rural westerners represent roughly a tenth of the region’s population and smart investments and policies can help these areas improve production, economic vitality, and quality of life important to any community.

Compared to the nation, rural Americans are older, fewer have a high school degree, their health outcomes are lower, they often lack adequate access to social services such as hospitals and schools, life expectancy is dropping, job earnings are lower and more volatile, and a significant portion of rural counties face significant and persistent poverty.

Some of these challenges have resulted from no fault of rural residents but simply because of the march of productivity. According to one study, 88 percent of the loss of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. from 2000 to 2010 can be explained by increases in productivity due to advances in labor-saving technology.

As efficiency increases, the number of farmers, miners, or laborers needed to maintain production has shrunk. And in many cases, new operations such as larger and larger farms increase output while simultaneously shrinking the workforce.

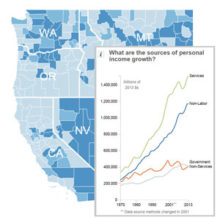

Today, for example, only five percent of personal income in western rural counties comes from direct employment in resource extraction activities such as mining, energy, or timber.

Overall, the economic sectors and businesses employing rural workers have changed dramatically. As a source of personal income today, government employment is 15 percent; services sectors such as health, engineering, education are 28 percent; manufacturing, construction and agriculture are 10 percent; mining, energy, and timber are 5 percent; and non-labor income such as retirement (pensions, Social Security and Medicare) and investments is 46 percent (all figures rounded).

Because of productivity increases and changing employment patterns, fewer rural workers have been needed in many communities, resulting in outmigration as workers and their families search for employment.

These population decreases then put pressure on local services—schools, grocery stores, or doctors—which often no longer have a population base sufficient to continue operating in a town or county. The result can be a reinforcing negative cycle that drives down population, diminishes taxes to support schools or law enforcement, and results in fewer customers for local stores.

Some rural areas have been reliant for years on a single industry—often tied to a commodity such as grain, energy, or beef—or related to a specific export market for rural manufacturing. This lack of economic diversity can leave a rural community vulnerable to the challenges described above.

In addition, it can place rural regions on a relative roller-coaster as commodity prices rise or decline, or export markets open or close based on outside factors such as the value of the dollar, trade agreements, or competition.

Finally, many rural areas are struggling to attract capital, whether public or private, to invest in their communities to remain competitive. State and federal assistance has been declining in real terms for almost all programs important to rural areas—whether for roads, airports, federal payments to counties, education, communications, or rural hospitals.

Private sector investment tells a similar story. Some communities have attracted significant new projects such as a data center or call facility, but many areas are struggling to spur significant investment.

Yet, some rural communities can and do compete in today’s economy. One key challenge is to reverse the brain drain where many younger rural residents are leaving for cities. Many states have initiated programs encouraging rural residents to return to their communities once they start raising families or are looking for more affordable cost-of-living options.

Rural advantages—whether tradition, way of life, lower costs, lighter taxes, or recreation opportunities—can be an important factor in retaining or attracting individuals, investors, or businesses. Rural manufacturing, for example, has declined in some rural areas of the West, but many success stories illustrate how businesses are growing and providing an important share of a town or county’s employment.

Why the Rural West Matters: New Policies Must Reflect the Region’s Wide Diversity of Communities and Opportunities

Future decisions and policies impacting the rural West will extend beyond the region and impact Americans across the country. While the region has many valuable assets and great potential, many rural communities are facing significant social and economic challenges. Unfortunately, current government and private sector approaches do not reflect current socioeconomic realities and often are failing rural citizens.

Our Rural West Insights series will document many of the challenges and opportunities facing this diverse region. The rural West already has many advantages such as high quality of life and lower cost of living. Going forward, updated, flexible, and varied policies will be necessary to provide rural towns and communities with the resources they need to compete in today’s economy.

One of the most important issues requires improving human capital in rural communities through efforts such investing in rural education to keep and attract families or train workers. Other steps include increasing the quality and availability of health care; expanding and upgrading infrastructure and communications networks to help rural communities more easily access larger markets; continuing agriculture programs such as the Farm Bill; and sustaining the quality of the landscape along with best practices for utilizing natural resources.