In recent years, rural regions have become a focal point for new development projects tied to national priorities, from critical mineral mining to renewable energy, tourism, and data centers. While these projects promise jobs and local investment, they frequently fail to provide long-term benefits that could be included in business recruitment strategies such as improved education, job training, affordable housing, or childcare.

Data show that economic activity in rural communities often falls short of providing lasting benefits to residents. Even the most economically productive U.S. counties are not immune to decline. For example, 70% of rural counties with the highest economic productivity—the top 10% of counties in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per worker—are losing population, indicating that economic activity is not translating to local benefits. Fewer residents mean shrinking tax bases, reduced school enrollments, and diminished capacity to support core public services.

Want research like this in your inbox?

Subscribe to our newsletter!

70% of rural counties with the highest economic output are losing population.

Many high-output rural counties are also dependent on narrow economic sectors: 41% are dependent on farming, 38% on mining, and 13% on manufacturing. These industries are prone to boom-and-bust cycles, which can create large revenue swings and make long-term planning difficult for local governments. These challenges are leading many rural community leaders to seek new tools to better capture benefits from economic activity, enabling investments in economic diversification and maintenance of critical services like schools and emergency response.

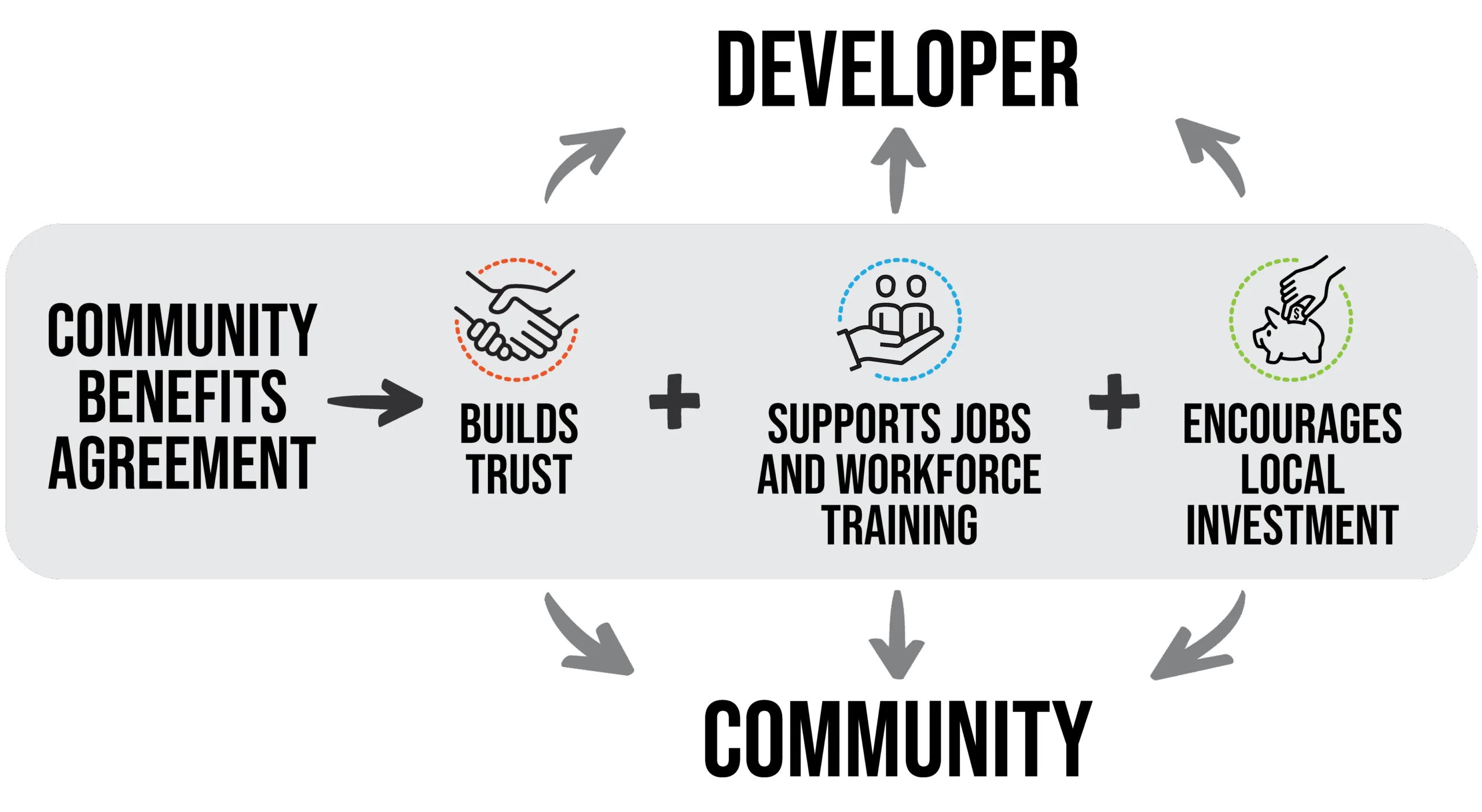

One promising tool is a community benefits agreement (CBA), a legal contract that can help communities capture long-term benefits from development to build local wealth and enhance community assets. While CBAs have historically been applied to urban development and large-scale industrial projects, they show potential across a range of emerging rural development needs. For example, a rural community struggling with workforce housing shortages might negotiate with a tourist resort developer to secure new funding for affordable housing. Another community might sign a CBA with a data center operator to establish a fund that supports economic diversification through workforce development programs or infrastructure investments.

How CBAs put community values first

A CBA is a mutually beneficial legal contract between a community coalition and a developer.

For developers, CBAs can proactively address local concerns, streamline community engagement, and decrease the risk of costly opposition and lawsuits. CBAs can help developers secure community buy-in for proposed projects, which can lead to expedited permitting processes and other cost savings.

For communities, CBAs can establish direct lines of communication with developers and create a path to new financial and community benefits. These investments do not need to be directly associated with the development itself; they might include childcare, affordable housing, workforce training, parks and recreation enhancements, or endowment funds. For example, negotiations between the community of Mount Pulaski, Illinois, and Swift Current Energy over a proposed wind farm resulted in a CBA that, in addition to requiring ongoing payments to an economic development fund, provided funding to preserve the town’s historic courthouse.

Communities can leverage CBAs to negotiate long-term and tangible benefits

Jobs & Labor

- Workforce training programs

- Local hiring and living wage requirements

- Local purchasing requirements

Affordable Housing & Transit

- New housing projects and renovations to existing homes

- Energy efficiency improvements

- Public transportation

Public Health & Education

- Infrastructure upgrades (water, wastewater, stormwater, etc.)

- Ongoing air or water quality monitoring

- Childcare services and education

Disaster Resilience

- Disaster mitigation & emergency services

- Resilience hubs or cooling centers

- Micro-grids (renewable energy & battery storage), back-up generators

Quality of Life

- Parks, green spaces, and recreation opportunities

- Biking trails and sidewalks

- Public art, local museums, cultural centers

Community Funding

- Community benefits fund and/or endowment fund

- Revenue sharing with developer

- Funding for staff

CBAs often include stipulations to establish an endowment fund or community grant program. These funds are typically created with one-time seed funding by the developer and may be supported by additional payments or revenue-sharing over time. In Nebraska, for instance, a CBA for a carbon storage project mandated an upfront investment of $500,000 plus an estimated $1 million per year based on the amount of carbon stored. Endowment funds, which protect the principal of the fund and only disburse investment earnings, are often considered best practice as they create long-term funding for communities. When a fund is non-endowed and allows the spending of principal, it is important for the community’s grantmaking entity to take a strategic approach to disbursements to ensure that they achieve substantial, coordinated impacts for the community or region. Both endowed and non-endowed funds can serve as important tools for making long-term community improvements.

The goal of a CBA is to create new community and economic development investments that would otherwise not be gained, helping the community achieve its long-term goals. Importantly, these investments are distinct from impact mitigation payments that offset costs associated with the project such as higher traffic volume, increased road damage, or greater demand for emergency services. Impact mitigation payments, though critical to maintaining and restoring public infrastructure and services, should be seen as required project costs, as opposed to a community benefit that would be negotiated in a CBA.

How CBAs are negotiated

Each CBA’s framework is established in negotiations between a developer and a local coalition, which can be a pre-existing group or can be formed specifically for this purpose. The most effective coalitions include individuals directly impacted by the project, as well as representatives from community organizations, businesses, faith groups, and regional partnerships.

Local governments typically do not lead or formally participate in CBA negotiations, but they can play a meaningful supporting role. For example, local governments can incorporate CBAs into ordinances or condition zoning approvals and tax incentives on demonstrated community support, bolstering a coalition’s negotiating leverage. Municipalities may also sign memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with local coalitions or help enforce CBAs by referencing them in development agreements. Local government staff and officials can also attend negotiations to ensure clear lines of communication among stakeholders.

However, local governments must navigate state-level legal constraints. Montana law, for example, restricts local governments’ ability to require affordable housing in new projects, though this is a common request made in CBAs. Because state law may restrict what elected officials can request from developers, local governments should seek legal counsel before becoming an “official party” in negotiations.

The limitations of CBAs

CBAs do have limitations. They cannot, for example, offset gaps in local or state regulations. The process can also be time-consuming and costly. By proactively forming local coalitions and tracking proposed developments, rather than forming coalitions in response to developments, rural communities can minimize the effort and cost required to negotiate a CBA.

The effectiveness of any CBA depends on, and is limited by, the local coalition’s negotiating power and ability to secure concrete benefits. In some cases, developers have been accused of co-opting the process, failing to address local needs, and violating agreements. While developers often have a team of lawyers for negotiations, communities may not have the same access to legal expertise. Detroit’s experience with its CBA ordinance offers important lessons for improving outcomes, highlighting the crucial need for local coalitions to have adequate time, resources, and information to negotiate advantageous terms.

Other strategies for smaller communities

When a CBA is not the right strategy, local governments and communities can employ other tools to incorporate community benefits into projects:

Development agreements and zoning ordinances. Development agreements, made between local governments and developers or property owners, often focus on infrastructure enhancements, impact mitigation, and adherence to municipal requirements. Some local governments have incorporated community benefit requirements or incentives into project-approval ordinances. For example, the development review process in Breckenridge, Colorado, scores projects that provide public benefits higher than those that do not, incentivizing developers to address community needs. This mechanism encouraged a developer to invest $2 million to help complete construction of a nonprofit hub as a condition for approval to build a hotel and workforce housing complex.

Host community agreements (HCAs). An HCA is similar to a CBA but is negotiated between the developer and the local government, rather than between the developer and a community coalition. HCAs typically include impact mitigation measures but can also provide community benefits. For example, a wind project developer agreed to pay the town of Byron, New York, a benefit fee expected to total $24 million over 20 years. Because some states prohibit inclusion of certain benefit types, HCAs can be more restrictive than CBAs.

Community funds. Many CBAs and HCAs require the developer to invest in a community fund, whether endowed or non-endowed. However, community funds can also be created independent of a CBA or HCA. Like the benefits ensured by a CBA or HCA, community funds should be differentiated from impact mitigation payments.

Landowner negotiations. When a project impacts multiple parcels, landowners can strengthen their position and ensure transparency by meeting together to discuss concerns and share information about proposed terms and conditions for leases and easements. Landowners may also choose to negotiate jointly with the developer. In Montana and North Dakota, landowners impacted by a proposed 420-mile transmission line formed a collective bargaining group to negotiate with the developer, Grid United. By pooling resources, the landowners were able to hire an expert lawyer and secure better lease agreements. Grid United saved time and money by only having to negotiate with one party.

Direct contributions to local priorities. When formal agreements are not possible—whether due to local capacity constraints or unwillingness on the part of developers—communities and local governments can still request payments and benefits. Though this strategy is ad hoc and likely to yield piecemeal results, it can nonetheless lead to meaningful investments. In connection with the Lincoln Land Wind project in Morgan County, Illinois, for example, Apex Clean Energy coordinated with a local broadband provider to fund new fiber installation to upgrade service for 250 customers.

Codifying community benefits in state law. To strengthen local communities’ negotiating power, some states have passed laws requiring CBAs or HCAs for large development projects. Since 2010, for example, Maine has required HCAs for wind projects, mandating that developers provide municipalities with transparent data in early planning stages, including projected revenue and local benefits. Maine’s statute also sets a minimum annual payment of $4,000 per wind turbine to the community.

Investing in long-term solutions

Rural communities often struggle to build community wealth and capture long-term benefits from economic activity. CBAs and related tools are proven strategies that communities can use to broaden the focus of planning and negotiation from mitigating development impacts to ensuring more concrete, long-term benefits for the community at large. These tools can be a win-win, offering developers clear processes for community engagement and project approval while empowering rural communities to address development more proactively and strategically.

Resources for learning more about CBAs

- Reimagine Appalachia: User-friendly information on community benefits agreements and an extensive library of guides, example agreements, and resources for rural places.

- Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia University’s Community Benefits Agreements Database: Examples of publicly-available community benefits agreements.

- Fair Shake Environmental Legal Services offers Community Benefits Agreements templates.

- Rural Organizing’s 2024 report “What small towns and rural leaders need to know about community benefits agreements.”

- Community Benefits Law Center’s 2016 report “Common challenges in negotiating community benefits agreements & how to avoid them.”