Late on the night of July 12, 2025, a wind-driven wildfire exploded on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, burning dozens of structures, including the historic Grand Canyon Lodge. Widely regarded as one of the most intact rustic lodges in the national park system, the structure has been reduced to stone pillars. Like many other beloved hotels in our national parks, the lodge was built by a railroad company in the first third of the 20th century and had burned before. Also like many historic properties across the United States, the lodge was partially built of wood. Its traditional construction, which helped secure its spot on the National Registry of Historic Places, contributed to its destruction.

Recent wildfires have also destroyed historic downtowns where many buildings were more than a century old and primarily constructed of wood. Greenville, California, a Gold Rush town with rows of colorful wooden storefronts, was razed by the 2021 Dixie Fire. The devastating 2023 wildfire in Lahaina, Hawaii, destroyed the town’s historic commercial core. And a 2024 wildfire complex destroyed nearly three-quarters of the historic town of Jasper, Alberta, in Canada.

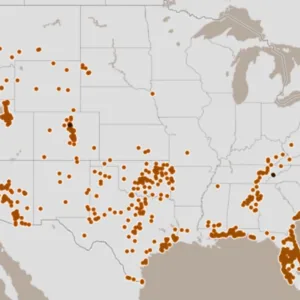

Nearly a quarter (24%) of public and private properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places fall within counties with high or very high wildfire risk, according to data maintained by the National Park Service and the USDA Forest Service. Many of these counties have high exposure to wind-driven urban conflagrations that can consume thousands of structures in hours. In all these counties, historic buildings—whether on the national registry or not—attract visitors, drive economic activity, and serve as cornerstones of local culture.

Despite nearly a quarter of properties on the National Register of Historic Places being in high wildfire risk areas, preservation protocols often restrict the use of measures shown to improve structural survivability.

Unfortunately, reducing the vegetation around these buildings – a practice known as improving defensible space – may not be enough to save them. Due to their flammable construction, historic structures are uniquely vulnerable to both wildfire embers and radiant heat. Windblown embers, which can travel miles ahead of the main flame front, are the leading cause of structure loss. When a single building is set alight by embers, the intense radiant heat can ignite nearby buildings without any flame contact. Many striking post-fire photographs, including those of the Grand Canyon Lodge, show completely destroyed buildings surrounded by mature, living trees – an indication that buildings are often at greater risk of burning during a wildfire than the trees that surround them.

Methods to reduce wildfire spread between structures are well known and increasingly integrated into building codes. But the guidance for restoring, rehabilitating, and reconstructing historic structures frequently contradicts wildfire-resistant building standards, even mandating the precise practices that wildfire protection standards discourage or ban. For instance, many wildfire-prone communities have banned or otherwise minimized the use of wood on the exterior surfaces of new buildings, including roofs, siding, and decks. Yet some of the same communities simultaneously mandate that historic building restoration continues to use wood.

Want research like this in your inbox?

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Likewise, years of deadly urban conflagrations have driven several states, including Colorado, Oregon, Washington, California, and Utah, to explore the adoption of building codes that ban combustible building materials in new construction in high wildfire risk areas. But even the most recent result of these efforts, the newly passed Colorado Wildfire Resiliency Code, exempts historic structures on local, state, and federal registries from its regulations.

Historic preservation is intended to ensure that the buildings that anchor many communities survive for generations to come. Yet many of these buildings include significant features made of highly flammable, centuries-old wood, making them costly to insure and hard for firefighters to save. Making sure that these treasured landmarks endure will require a shift in preservation policy. To date, however, historic preservation practices and standards—including the federal standards used by government agencies and private-sector preservation professionals alike—have not adapted to increases in wildfire risk. Many of these standards continue to encourage practices that make wildfire losses likely.

The Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, for example, does not provide substantive recommendations to improve the survivability of a historic building in a wildfire. These high-level standards have remained largely unchanged since they were first written in the 1960s, although the federal government has issued several updates in the form of guidelines or policy briefs. In terms of disaster adaptation, the most consequential of these, “Guidelines on Flood Adaptation for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings,” seeks to correct the decades-old decision to exempt historic structures from flood protection measures by offering preservation alternatives for properties facing flood risk.

It is the federal government’s intent that communities should avoid making the same mistake with buildings exposed to wildfire risk. To encourage adaptation, the standards now suggest that special exceptions or variances may be considered to protect a building from known hazards, although wildfire-related criteria or examples have not yet been provided. These details are forthcoming — the Department of the Interior expects to publish a wildfire-specific policy brief in 2026.

Historic buildings face unique risks

Historic downtowns across the country were built and designed before the advent of modern building codes and fire safety practices. In the early 19th century, the frequent fiery devastation of downtowns and large portions of cities inspired building codes, water infrastructure such as fire hydrants, and the first paid fire departments. By the 1830s, in an ongoing effort to curb urban fire, cities including Boston, Philadelphia, and New York had widened streets and transitioned from mostly wood-frame construction to less combustible materials such as brick or steel.

Sherman St. in Deadwood, South Dakota, 1909. Source: Leeland Art Co. via Library of Congress

However, even with today’s building codes in place, historic downtowns remain susceptible, especially in counties with high wildfire risk. In many cases, the risk is compounded not only by flammable materials—such as the wooden sidewalks and building facades still in use in many towns in the American West—but also by structural densities. Densely built downtowns form a continuous wall, creating a feeling of enclosure and intimacy on the street, but adjoining buildings with shared wooden roofs and conjoined attics help fire spread more swiftly. Older town centers with narrow, historically charming streets are also difficult for fire trucks to navigate.

Once wildfire sweeps through a community, historic buildings that have been damaged are difficult and expensive to repair; those that have been destroyed are often irreplaceable. If a historic building is under the regulatory authority of a city, state, or federal agency, there may be limits on what kinds of materials can be used to restore it, and restoration may require specially trained professionals. Given that these unique sites cannot be easily or affordably recreated, investing in wildfire-resistant restoration is a sound strategy.

The path forward

A wide range of measures can help protect historic structures in wildfire-prone areas. Most, including the use of ignition-resistant building materials and landscaping practices, can be designed and implemented to meet the objectives of both preservation and wildfire resilience. Key strategies include the following:

1. Issue guidelines for wildfire adaptation of historic buildings

The DOI’s standards and guidelines for historic preservation are followed by every federal agency and by many state historic preservation offices, local governments, and private-sector preservation consultants, architects, and contractors. Collectively, these standards and guidelines discourage the use of nonhistorical materials for replacements or rehabilitation, effectively forcing most communities to sacrifice their historic buildings’ resilience and safety for the sake of their historical integrity. Recent losses of historic buildings in fire-prone communities demonstrate an urgent need to update DOI’s technical guidelines.

DOI should issue guidelines, similar to its guidance on flood adaptation, that encourage the use of alternate, wildfire-resistant materials for repairs to buildings that face high fire risk. For example, these guidelines should acknowledge that wood-shake shingle roofs are a significant fire hazard and recommend replacing them with safer materials that mimic the original look but reduce the risk. The development of new guidelines represents a significant undertaking, requiring a multi-year effort by the DOI; yet it is an essential step.

The following table illustrates opportunities to update the DOI’s guidelines to align with wildfire risk-reduction goals in the built environment.

| Summary Definition from DOI Standards | Current Focus of Standards | Recommendations for Wildfire Resistance | |

| Preservation | “The act or process of applying measures necessary to sustain the existing form, integrity, and materials of an historic property” | Ongoing maintenance and repair of historic materials and features | Allow minor building retrofits such as ember-resistant vents and metal flashing in key areas.Establish a non-combustible zone within 5 feet around any structure. Remove plants and bark mulch and replace with hardscaping if possible.Follow guidelines for establishing defensible space within 30 feet of the structure. |

| Restoration | “The act or process of accurately depicting the form, features, and character of a property as it appeared at a particular period of time by means of the removal of features from other periods in its history and reconstruction of missing features from the restoration period” | Preservation of materials, features, finishes, and spaces from a specific period of significance and removing those from other periods | In addition to those above: Explicitly allow the substitution of non-combustible materials for restorations, such as fiber cement siding, to preserve a sense of history even in the absence of truly historic materials. |

| Rehabilitation | “The act or process of making possible a compatible use for a property through repair, alterations, and additions while preserving those portions or features which convey its historical, cultural, or architectural values” | Allowances for alterations to meet continuing or new uses as long as historical character is maintained | In addition to those above: Allow more significant building modifications, such as replacing windows with dual-pane tempered glass windows and allowing Class A roof coverings.Allow window frames to be replaced with metal-clad options. Do not require wood-frame window replacements.Require additions and new construction to use ignition-resistant materials, such as composite decking. |

| Reconstruction | “The act or process of depicting, by means of new construction, the form, features, and detailing of a non-surviving site, landscape, building, structure, or object for the purpose of replicating its appearance at a specific period of time and in its historic location” | Establishment of a limited framework for recreating a vanished or non-surviving building with new materials, primarily for interpretive purposes | In addition to those above: Generally prohibit the use of combustible materials on the exteriors of buildings. |

2. Stop exempting historic properties from hazard-safety-related land use policies

Building codes and regulations should not grant wholesale exemptions for historic properties and structures when it comes to meeting wildfire risk reduction measures. Instead, in wildfire-prone communities, land use policies should discourage the use of wood and other combustible materials in all construction, including the restoration of historic buildings and districts. Rather than waiving hazard-safety requirements for historic buildings, local, state, and federal offices can craft land use policies that focus on desired outcomes that balance risk reduction and historical integrity. For example, policies can require property owners seeking to obtain restoration permits to undertake a professional wildfire risk assessment and submit a plan that addresses the resulting recommendations.

3. Understand the community’s wildfire risk

Any community effort to protect historic structures should begin by understanding local wildfire exposure and risk. Free community-level risk maps are available at the USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Risk to Communities website, which provides risk data and resources designed for community leaders, including elected officials, community planners, and fire managers. In addition, many states have produced wildfire maps that provide useful information for understanding local risks.

Understanding local risks and solutions also involves assessing the degree to which wildfire-resistant building practices are already in use. A growing body of research demonstrates that these practices are highly effective at reducing losses. For example, studies have shown that homes built to wildfire-resistant standards are as much as 40 to 60 percent more likely to survive a fire. These building practices help protect structures from a variety of wildfire exposure scenarios, including direct flames, radiant heat, and embers, to which historic buildings with wood siding, roofs, or other combustible elements are especially vulnerable.

4. Document the community’s assets

The first step in saving historic buildings is identifying them and documenting their significance. Though detailed records exist for properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, communities can also maintain their own digital records of locally significant buildings. Records that include drawings with details about the character and defining elements of properties and buildings can be particularly useful when a structure is destroyed or damaged by wildfire. Another benefit of maintaining records for historic buildings is that historic designations can make buildings or property owners eligible for tax incentives or funding to replace, repair, or modernize certain aspects of buildings.

Communities can also encourage property owners to register buildings with state or federal historic registries. Not all buildings will be eligible, and some registries (particularly at the federal level) restrict the types of improvements that can be made.

Ideally, local historic preservation ordinances identify the aspects of a historic district prioritized for preservation or, in the case of disaster, reconstruction. Designated historic districts can also mandate architectural standards for new buildings; zoning regulations in Santa Fe, New Mexico, illustrate this approach to preserving a sense of history even in the absence of truly historic structures. Ensuring that new buildings echo the form and scale of historic districts but use noncombustible materials is an effective compromise that helps reduce wildfire risk.

5. Adhere to fire-resistant landscaping practices

All historic buildings can benefit from landscaping that reduces wildfire risk. Scientific research on risk reduction has shown that a “noncombustible zone,” with no flammable materials within five feet of a structure, is highly effective. This guidance, based on years of detailed studies of how structures burn during wildfires, applies to potted plants, trees, garden boxes, wood mulch, wood piles, and furniture, among other materials. For historic structures, this means changing landscaping designs and practices around buildings.

Importantly, while research has demonstrated the benefits of fire-adapted landscaping, the limited research on exterior sprinkler systems has yet to prove their effectiveness. If used, exterior sprinkler systems should be connected to an alternate power source, such as a backup generator, as grid electricity may fail during a wildfire.

Communities can also reap additional benefits from establishing five-foot noncombustible zones around historic structures. Hardscaping—replacing vegetation with stone—can deter termites and rodents, and keeping trees away from structures can protect foundations, roofs, and pipes from damage caused by branches or roots. In addition, landscaping solutions that improve wildfire safety can help conserve water in communities that face droughts and water shortages; in other words, fire-adapted landscaping tends to be water-wise. However, in cases where some vegetation within five feet of the historic building cannot be avoided, the plants should be well-watered because fire spreads quickly through dry vegetation.

6. Stay ahead of building and property maintenance

Owners of historic buildings often modernize electrical systems to minimize the risk of fires that start inside buildings. They should also follow best practices to avoid the spread of fires that start outside.

In addition to requiring or encouraging noncombustible zones around structures, historic preservation policies and practices should encourage building owners to clean behind wooden facades, removing the pine needles and other debris that can collect there and provide extra fuel for fire. Property owners should also have a plan for wildfire season and for when a fire is near, including moving outdoor furniture inside, closing windows, and cutting back flammable landscaping.

Adapting to fire, preserving history

Historic buildings and districts contribute significantly to local economies, particularly in rural communities, and preserving them is a high priority. As wildfire risk spreads and intensifies, many communities are reexamining how best to achieve this goal. In the effort to balance historical integrity and wildfire preparedness communities may face difficult decisions about tradeoffs. But the path forward is becoming clearer, especially as alternative materials continue to improve and offer both increased fire resistance and authentic appearance. Just as cities adapted to the risk of urban fires two centuries ago by updating building practices and installing fire hydrants, many communities today can adapt to wildfire risk and also preserve their cultural and architectural history.

Acknowledgements

Susan Riggs of Groundprint, LLC contributed knowledge and expertise to this research.