Extreme heat is often portrayed in research and the media as an urban issue with popularized terms like the “urban heat island effect.” Yet almost every state in the contiguous United States has rural communities where the likelihood of experiencing heat-related health problems is above the national average.

Headwaters Economics and the Federation of American Scientists collaborated on an analysis of the risk that extreme heat poses to rural communities. The following report shows heat risks in rural ZIP codes, explores what makes rural communities vulnerable, and identifies policy solutions that will protect people from rising temperatures and save lives. Strategies to address extreme heat should be designed with the infrastructure and capacity of rural communities in mind.

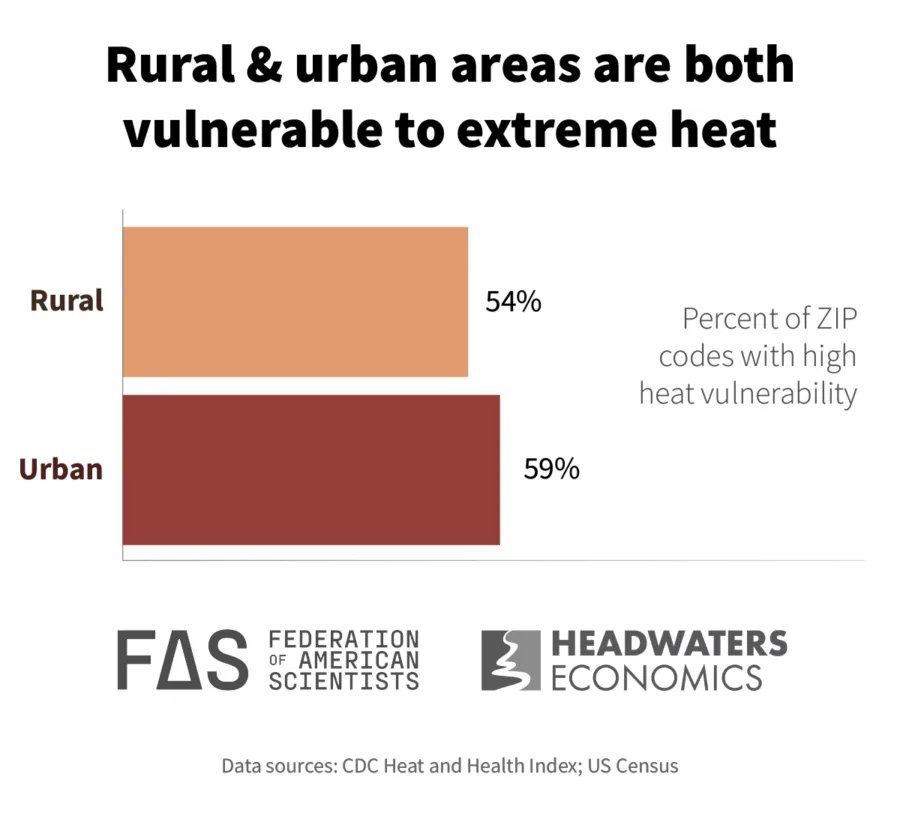

Rural communities are just as vulnerable to extreme heat as urban communities

Slightly more than half of urban ZIP codes (59%) and rural ZIP codes (54%) have high heat vulnerability.

In this analysis we define rural ZIP codes as those where the median drive time to the nearest urban center exceeds 1.5 hours. We use the Heat and Health Index, produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to identify where people are most likely to feel the effects of heat on their health and to identify ZIP codes where vulnerability to extreme heat exceeds the national median. (See Data Sources & Methods below.) The Heat and Health Index is based on 25 indicators that capture historical heat days and health impacts, health sensitivities in the population, sociodemographic factors that increase vulnerability (such as age and poverty), and the natural and built environments (such as housing conditions and tree canopy).

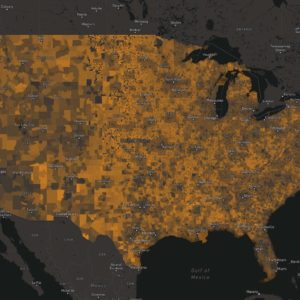

The interactive map below shows where rural and urban ZIP codes have high heat vulnerability. The 10 states with the highest share of their population living in rural areas facing high heat vulnerability are Oregon, Oklahoma, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Ohio, Arizona, California, Virginia, and Kentucky.

On average, Americans living in rural ZIP codes are twice as likely as those living in urban ZIP codes to have pre-existing health conditions that make them sensitive to heat. Nearly every state in the contiguous United States (45 of 48 states) has rural ZIP codes where the likelihood of experiencing heat-related health problems is above the national average. The only exceptions are Connecticut, Indiana, and New Jersey, which have no rural ZIP codes as defined in this analysis.

Rural Americans are twice as likely to have health issues that raise their risk from extreme heat.

In total, 11.5 million Americans are living in rural ZIP codes with high vulnerabilities to extreme heat. The causes of heightened health-related heat vulnerability in rural areas include age, the prevalence of certain health conditions, housing characteristics, and types of employment.

The unique heat vulnerabilities of rural communities

Rural areas are especially vulnerable to heat due to older housing, poor infrastructure, and geographic isolation, as well as demographic factors like age, outdoor work, and medical conditions. Vulnerable groups include children, pregnant people, older adults, people with disabilities, and those with chronic illnesses such as asthma or heart disease. Heat-related risks in rural areas are further influenced by living conditions, access to cooling, transportation methods, and outdoor occupations.

Weatherized, energy-efficient housing is one of the key protective factors against extreme heat, yet the rural housing stock is often older and lacks adequate cooling. Further, manufactured and mobile homes—comprising 12% of the rural housing stock as opposed to 4% of the urban housing stock—are one of the most heat-vulnerable housing types. Due in part to energy-inefficient housing, rural residents spend 40% more of their income on energy bills than their urban counterparts, and rural residents in manufactured and mobile housing spend 75% more. These costs are only expected to rise as cooling demands increase, compounding energy debt burdens that lead to households choosing between paying rent on time or purchasing food or medicine.

Power outages, increasingly triggered by heat-related grid stress, wildfires, and storms, pose additional risks. Geographic isolation, limited resources, and older infrastructure limit the frequency of maintenance and speed of repairs in rural communities. As a result, restoring power in rural areas takes significantly longer, threatening health and economic stability.

Heat also undermines rural economies reliant on outdoor labor and recreation. Hundreds of rural counties depend on outdoor tourism and natural resource industries. Seven percent of the workforce in rural communities is employed in farming, forestry, or mining. Another 6% work in construction. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat threatens the health of outdoor workers. Outdoor laborers are one of the most at-risk populations, yet only eight states have regulations that mandate protections for workers.

Rural residents are also more likely to be medically vulnerable and underinsured or uninsured. This means when people need medical care because of heat-related illness, they will be saddled with thousands of dollars in medical expenses. These vulnerabilities are compounded by limited public health infrastructure in rural places. Many rural communities lack district, county, or city public health departments, and those that have them struggle to maintain adequate funding and staff. More than 100 rural hospitals have closed in the last decade and many more are at risk.

Finally, rural-specific data gaps hinder the creation of tailored solutions designed for rural places. For example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Heat and Health Index uses a “built environment” measure that favors urban communities by focusing on impervious surfaces and tree canopy. This index is no longer maintained as of the date of this publication.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Policy solutions to prepare rural communities for extreme heat

2024 was the hottest year on record, capping a decade of escalating heat extremes. Readying rural communities for a future of extreme heat will require tailored policy solutions at the local, state and federal levels. The following recommendations focus on reducing risks through targeted research, infrastructure investment, workforce protections, and public health capacity.

- Design solutions that reflect rural realities

Rural communities experience extreme heat differently than urban areas due to geographic isolation, dispersed populations, outdated infrastructure, and outdoor labor forces. Yet many current heat adaptation strategies—like cooling centers, tree canopy targets, or cool corridors—are designed for urban settings and do not scale well to rural contexts. Federal and state agencies should support rural-specific planning and design solutions with local stakeholders. Relying on trusted networks, like agricultural extension services, can help translate strategies into action. - Expand rural capacity through research, data, and funding access

Effective rural heat adaptation is limited by major capacity gaps. A lack of data hinders rural decision-making and resource allocation. Many rural communities need capacity and staffing to track heat-related health and economic impacts or to apply for complex, competitive funding. Federal and state agencies should:- Invest in rural-specific research and data systems to track heat-related illness, productivity losses, and economic disruption like agricultural losses or tourism declines.

- Expand technical assistance to help rural communities access and manage funding.

- Create direct or simplified funding applications that account for capacity limitations in rural communities.

- Invest in rural infrastructure that keeps people safe and cool

Rural communities need substantial improvements to housing, energy, and grid infrastructure to prevent cascading energy and health crises that will cost taxpayers more in the long run. Policymakers should continue federal funding sources, such as the Weatherization Assistance Program, Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), the Inflation Reduction Act’s Home Energy Rebates, and IRS energy-efficiency tax credits to weatherize homes, reduce cooling costs, and lower energy burdens for vulnerable households. The Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) can also support grid hardening, distributed energy solutions, and microgrid deployment, reducing the likelihood of power failures. Integrating these programs through coordinated technical assistance and rural-specific delivery models will amplify impact and reach. - Protect rural outdoor workers and rural economies

Rural economies rely heavily on outdoor labor that is highly vulnerable to extreme heat. Federal and state agencies should develop and promote practical, evidence-based workforce protections (e.g., rest, water, and shade protocols). Worker protections must align with the economic realities of rural businesses to ensure both health and productivity are maintained. Small businesses, including many farming operations, will need technical and financial assistance. Solutions to mitigate the impacts of extreme heat on workers and businesses will be critical for sustained rural economic development. - Expand rural public health and healthcare capacity

Rural health systems are the first line of defense against heat-related illness, yet many are underfunded and overstretched. Policymakers should provide flexible and sustained funding—modeled after the Emergency Rural Health Care Grants deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic—to support rural hospitals, clinics, and public health departments in preparing for and responding to extreme heat. Investment should prioritize staffing, mobile response capacity, and preparedness for heat-related illnesses.

Data Sources and Methods

To conduct the analysis, Headwaters Economics used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Heat and Health Index (HHI), dated 2024. The Heat and Health Index helps identify communities where people are most likely to feel the effects of heat on their health. It incorporates historical temperatures, heat-related illness, and community characteristics at the ZIP code level to identify areas most likely to experience negative health outcomes from heat and help communities prepare for heat in a changing climate. The HHI is not available for Alaska and Hawaii.

For the purposes of this analysis, we used the following definitions:

- “High vulnerability to extreme heat” is defined as ZIP codes that are in the top 50th percentile of the CDC’s Heat & Health Index.

- “Rural ZIP codes” are defined as having ≥1.5 hr. median drive time to the nearest urban centers (population ≥ 50k).

- “Urban ZIP codes” are defined as having ≤15 min median drive time to the nearest urban center (population ≥ 50k).

ZIP codes that meet neither the “Rural” nor “Urban” definitions above are excluded from the analysis.

Acknowledgments

Grace Wickerson, the Senior Manager of Climate and Health at the Federation of American Scientists, contributed knowledge and expertise to this project. Grace leads work highlighting how climate change affects health and healthcare systems, focusing on threats like extreme heat and wildfire smoke.