Communities with outdoor recreation economies are rich in natural assets such as mountains and rivers, but their proximity to these resources also puts them on the front lines of natural hazards such as wildfire and flooding.

Outdoor recreation communities often experience disproportionate economic and social impacts from disasters because of their reliance on natural assets. Damage to infrastructure such as roads or water systems can keep away the visitors that keep local businesses operating. The loss of homes can displace families and workers and increase real estate prices—which already tend to be higher than the national average—and make recovery even more difficult. The increasing severity of disasters has many community leaders looking for solutions that can be tailored to the unique needs of outdoor recreation destinations and the people who call these places home.

To shed light on these concerns, Headwaters Economics conducted a data analysis of disaster risks facing outdoor recreation economies. We also surveyed a range of solutions that communities are already using to prepare for more frequent and severe natural hazards. The results demonstrate how local, state, and federal policy can help disaster-prone outdoor recreation communities prioritize updates to infrastructure, land use plans, and emergency response systems.

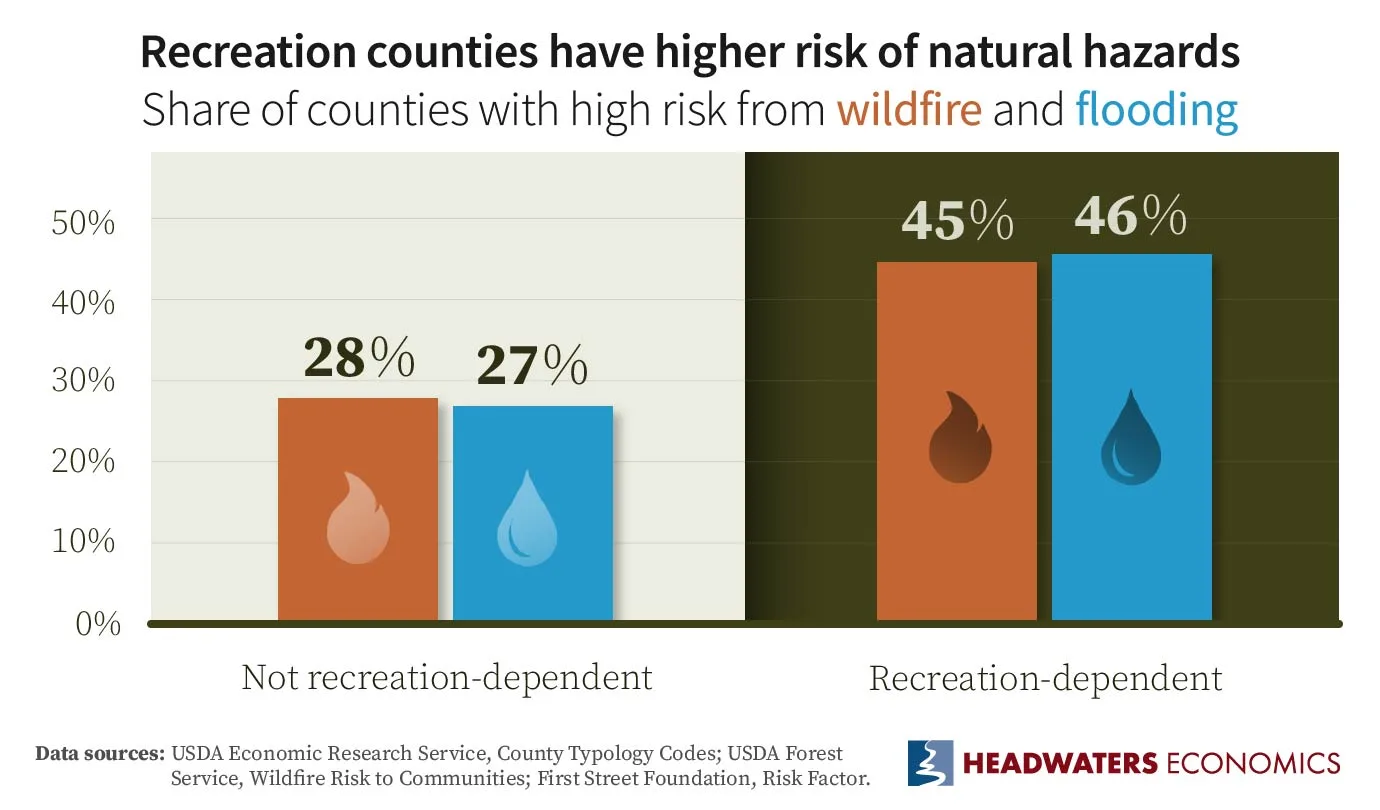

Recreation-dependent communities face much higher wildfire and flood risks than others

Nearly half of the 425 outdoor recreation counties in the United States have a high risk of wildfire or flooding, according to federal data sources. Forty-five percent of recreation-dependent counties have high or very high wildfire risk compared to 28% of non-recreation-dependent counties. Forty-six percent of recreation-dependent counties have high or very high flood risk compared to 27% of non-recreation-dependent counties.

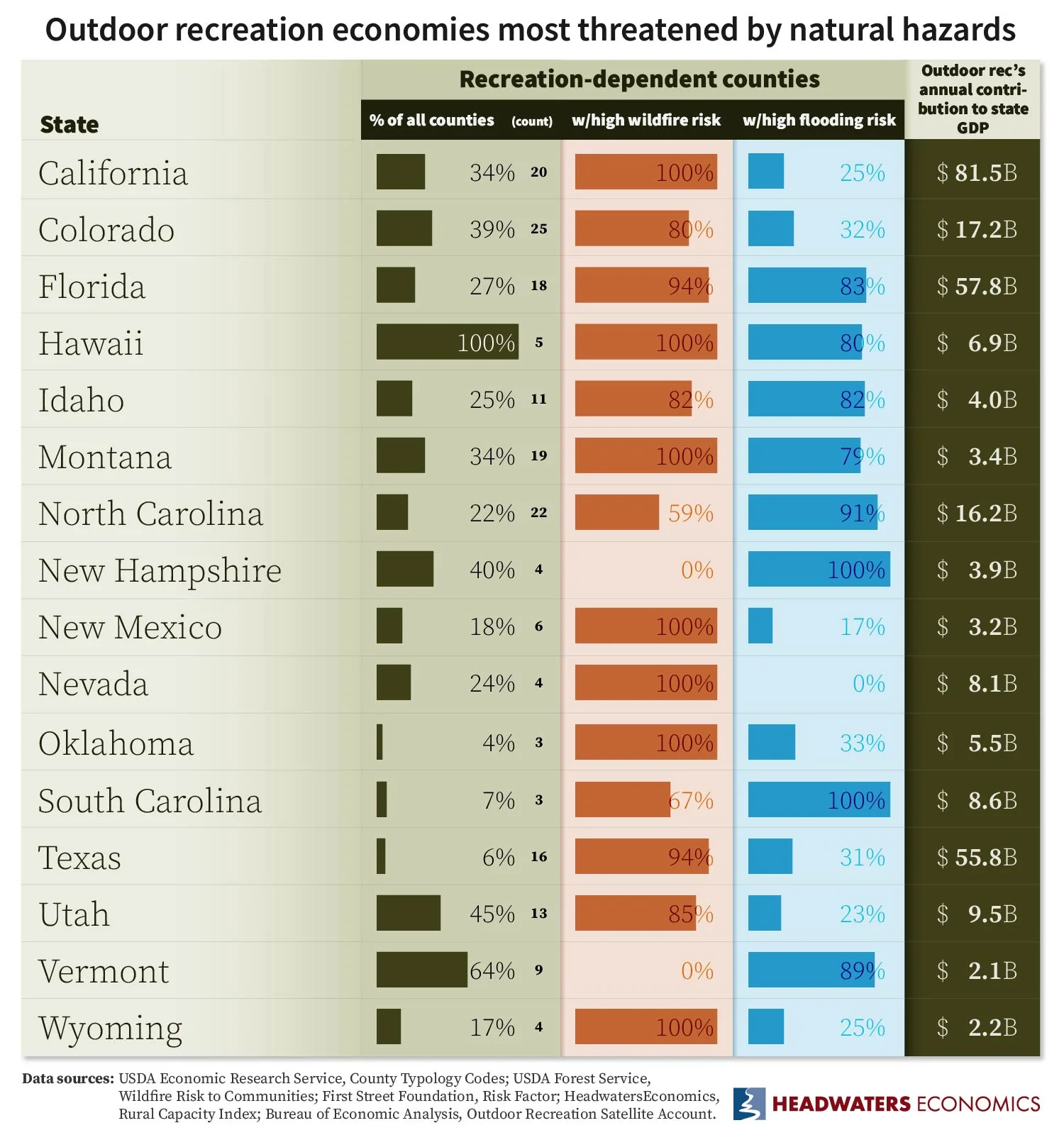

Some states are particularly vulnerable

There are 16 states where nearly all the recreation-dependent counties—and therefore their outdoor recreation economies—are at high risk of wildfire, flooding, or both. In each of these states, outdoor recreation contributes billions of dollars in economic activity.

A lack of local government capacity can make investing in solutions difficult

Communities that aspire to become more resilient to natural hazards must make significant investments in updating infrastructure, emergency plans and response systems, and community plans and zoning regulations. While federal, state, and philanthropic grants are available, many communities do not have the capacity—the staff, resources, and expertise—to apply for those grants, fulfill complex reporting requirements, and design, build, and maintain infrastructure projects over the long term. Our analysis shows which recreation-dependent counties in the United States have low capacity and a high risk of wildfire, flooding, or both.

Places that depend on outdoor recreation urgently need to improve their hazard resilience. This will require concerted efforts at local, state, and federal levels.

Solutions for communities

An examination of places working to preserve their outdoor recreation economies from increasing disaster risk reveals three primary strategies that can be effective.

Communities can explicitly incorporate natural hazard resilience into their community and economic development plans. Some specific approaches include:

Implementing zoning regulations, building codes, and design standards that increase hazard resilience in buildings, infrastructure, and trails and trailheads.

Using parks and trails to improve flood storage, create fire breaks, and improve firefighting access.

Managing watersheds to support recreation and mitigate fire and flood risk.

Creating and marketing shoulder-season recreation opportunities when flood or fire risk is lowest.

Whistler, BC, Canada

Communities can involve destination management organizations (DMOs), tourism-related businesses, and outdoor recreation advocates in disaster planning and response to address needs of visitors and part-time residents. Approaches include:

Building relationships with community foundations, municipal governments, community organizations active in disasters (COADs), and state agencies before disasters happen.

Educating visitors and part-time residents about disaster risks prior to disasters.

Developing communication plans specific to visitors and part-time residents during disasters.

Communities can develop tourism-related funding sources to finance hazard mitigation and preparedness. For example:

Using a portion of lodging tax or local option sales tax revenue to fund disaster resilience.

Bundling hazard resilience projects with outdoor recreation projects can increase community support and create more funding opportunities than projects that include only one category of benefits. It’s often easier to garner support for tangible improvement such as new parks, trails, and river access rather than mitigation for disasters that a community may not have experienced and might have a hard time imagining.

Projects with multiple types of benefits are also eligible for multiple funding sources. In Ogden, UT, for example, a large river restoration project that protected the community’s sewer line also created a community park and whitewater feature, removed invasive species, and restored wetland and riparian habitats. Funding for this project came from a wide variety of sources, including local and state organizations, federal agencies, nonprofits, and private foundations, that might not have been available if the project had a narrower scope of benefits.

State government and federal agency support

While much hazard resilience work occurs at the municipal or county level, there is also role for state government and federal agency support.

For example, state and federal grant-making for outdoor recreation-related projects can prioritize projects that incorporate hazard mitigation or require that applications for funding address some aspect of resilience. State-level programs can create revolving loan funds for property buyout programs that help communities waiting for the slower FEMA buyout process, as the Harris County Flood Control District did in Texas. This kind of program would support rural and under-resourced communities especially, and outdoor recreation communities generally.

At the federal level, resilience policies should consider the specific needs and constraints of rural and low-capacity communities that depend on outdoor recreation. Many of these communities host visitor populations that are much larger than their year-round population, which can make it difficult to build infrastructure at the scale their community requires. They can also face challenges in obtaining federal support, since many competitive grant programs, such as FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) and U.S. Department of Transportation’s Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE), require benefit-cost analyses that are inherently weighted toward places with larger populations.

Other requirements to protect resources, such as Clean Water Act compliance, only apply to communities with a population above a set threshold. For example, the Municipal Separate Storm Water Sewer System (MS4) program enforces a set of engineering best practices designed to prevent excessive runoff and water quality degradation. This program only applies to communities with more than 10,000 year-round residents, leaving smaller communities that have large seasonal populations without sufficient water quality protection. Federal allowances for these tourism-dependent communities, paired with state technical, and financial assistance, could support their unique needs.

State, federal, and philanthropic partners that provide financial support to communities for outdoor recreation or natural hazard resilience should also recognize that many places do not have the staffing, local expertise, or financial resources to compete for or administer complex grants. Using resources such as the Rural Capacity Index to target these communities with financial support, technical assistance, and capacity-building for implementation can help to reduce the barriers these places face.

Disaster resilience in recreation-dependent communities is more critical than ever

The economic impacts of disasters in recreation-dependent communities—which can include reduced visitor numbers, business revenue and job losses, reduced housing supply, and diminished tax revenue—can reverberate for years, creating local budget deficits and financial hardship for residents.

As demonstrated by this research, outdoor recreation communities will need to implement a range of solutions—from updating resource management plans to reinvesting tourism revenue—to address their growing exposure to disasters and reduce risk. Reaching these goals will require support from state and federal agencies, charitable foundations, and businesses. A coordinated investment of resources and technical assistance are needed to protect residents and visitors and secure the continued vitality of recreation-based economies for the future.

The analysis and conclusions of this post are also detailed in a printed report, “Future-proofing the outdoor recreation economy.”

Data Sources and Methods

This analysis examined data from several public and private sources. Wildfire risk data came from the Wildfire Risk to Communities. Flood data came from First Street’s Flood Factor. Outdoor recreation data was collected from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service. Data about outdoor recreation contributions to state GDP is from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account. Rural capacity data came from Headwaters Economics’ Rural Capacity Index.

Acknowledgments

Chloe Braedt

Chloe Braedt is a recent economics graduate from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. She analyzes environmental and economic data to help communities protect spaces for wildlife and outdoor recreation, address natural hazards, and build economic resilience.