Spanning more than 3,700 miles, the Great American Rail-Trail® travels through 12 states and the District of Columbia, connecting trail users and communities between Washington D.C. and Washington state.

As the nation’s first cross-country multiuse trail, the Great American Rail-Trail will be entirely bikeable and walkable, connecting travelers of all ages and abilities with America’s diverse landscapes and communities. It will be hosted primarily by rail-trails—public paths created from former railroad corridors—as well as other multiuse trails, offering a route across the nation that is completely separated from vehicle traffic. The Great American Rail-Trail is currently 53% complete, with more than 150 existing trails hosting the route and approximately 88 gaps yet to be connected.

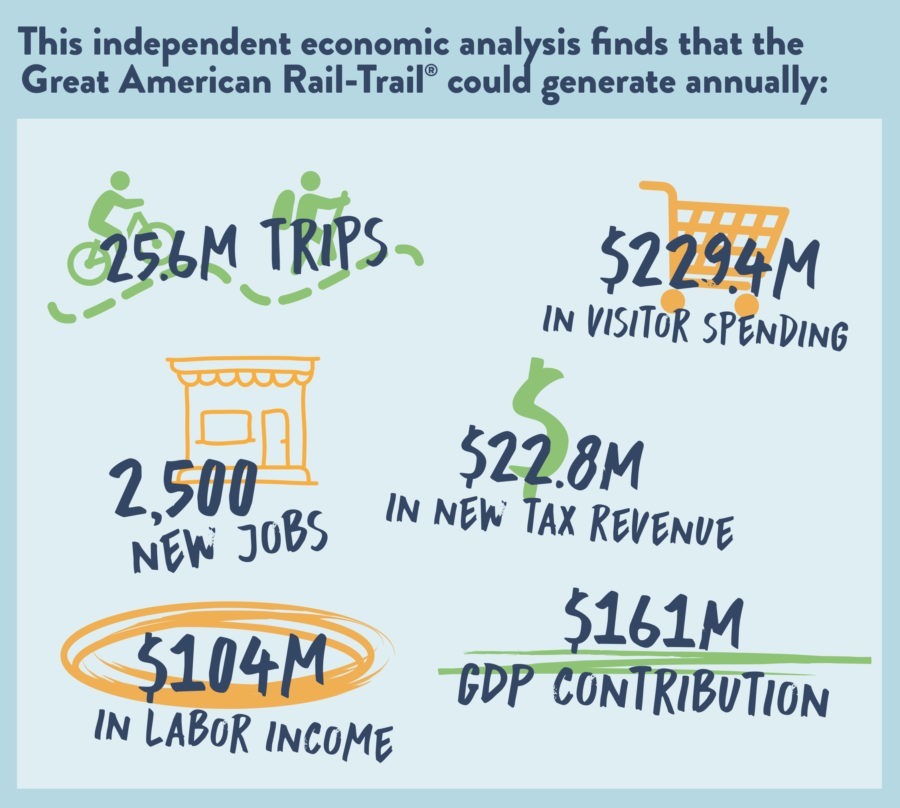

Headwaters Economics partnered with Rails-to-Trails Conservancy to conduct an independent economic impact analysis of the Great American Rail-Trail. We find that when fully complete, the trail will attract 25.6 million trips and generate more than $229.4 million in visitor spending each year. It could generate more than $104 million in labor income, 2,500 new jobs, $22.8 million in new tax revenue, and contribute more than $161 million to the gross domestic product each year.

The completion of the Great American Rail-Trail will help amplify the benefits— on a mass scale—that trails provide. In addition to offering places for physical activity and recreation, connecting diverse communities with safe walking and biking routes, and promoting a closer connection to nature, the Great American will help communities along the route realize new economic potential.

To fully realize the economic opportunity of the Great American Rail-Trail, communities will need to plan for and invest in the trail. Gaps will need to be connected and infrastructure like trailheads and signage are needed. States and communities can support tourism-ready businesses along the route. The trail will need to be built and maintained at a level of quality that allows most skills and abilities to walk, bike, and roll. If such investments are made, all 12 states along the route can realize its benefits.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Data Sources & Methods

Economic impact analyses are based on the idea that something—whether a new trail, new business, or a new policy—can attract new money by enticing visitors who otherwise would not have come to the area. This new money, in turn, supports local businesses that employ residents, pay taxes, and support other businesses. These analyses require measuring the number of visitors drawn to the area and how much they spend.

Headwaters Economics partnered with the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy to conduct this economic impact analysis for the Great American Rail-Trail using four data elements: 1) existing trail count data; 2) original statistical models to estimate trail users; 3) a literature review of spending estimates and trail use characteristics; and 4) economic impact estimates from the IMPLAN economic modeling program. For complete data sources, see the Methods and Data Sources Report.

The economic benefits presented in this analysis rely on three underlying assumptions. First, we assume that communities will capitalize on the trail with businesses like gear shops, restaurants, and lodging; signage directing users to these local businesses; and marketing the community as a welcoming stop for trail users. Second, we assume that the increase in outdoor recreation observed during the pandemic will persist. This assumption is supported by data from Rails-to-Trails Conservancy’s national network of trail counters and the Outdoor Industry Association’s national survey on participation in outdoor recreation. Finally, we assume that the route in this assessment will be built and maintained at a level of quality that is connected to other segments; has a safe separation from vehicles; and has a surface that is sufficiently maintained to allow most skills and abilities to walk, bike, and roll. This analysis does not assume that all segments would be paved.

The statistical modeling to estimate the number of trail users was conducted at the county level, using trail counter data from 57 locations across the U.S. to calibrate the model. In counties where trail counter data were available, we used the actual trail use. Where counter data were not available, we built on a statistical model developed by Rails-to-Trails Conservancy to predict use. The model uses communities of a similar size, climate, wealth, and population density. Due to the inherent variability and uncertainty underlying statistical modeling, we calculated the likely range of predicted use, and throughout the report provide the mid-point. The numbers provided in this analysis report the impact of a trail that is 100% complete. In states where the Great American Rail-Trail is not yet completed, the benefits today are proportional to the percentage of trail that is complete.

We relied on 30 existing studies of long-distance trails across the U.S. to estimate the share of users that are visitors versus locals, the share of visitors who are overnight versus day users, and spending profiles for overnight and day visitors. Where recent data were available for a specific trail segment we used segment-specific data. Otherwise, we applied averages from the literature.

The spending and visitation estimates were input into IMPLAN, a regional economic modeling software, to estimate the jobs, income, tax revenue, and contributions to GDP likely from the completion of the Great American Rail-Trail.

For complete methods, definitions, and data sources, see the Methods & Data Sources Report.