- State trust land managers sometime fail to maximize revenues from traditional activities such as grazing, timber production, and mining.

- New types of value provided by state trust lands—such as recreation, biodiversity, and aesthetics—are difficult for states to monetize in private markets, so trust lands are usually not managed for these uses.

- In rare cases, conservation or recreation groups have won bids to lease trust lands for new uses.

- States may consider compensating the trust to meet emerging public demands or redefining their fiduciary trust obligations.

State Trust Lands in Transition

This report is in a four-part series seeking to better understand state trust lands in the western economy and landscape. The series includes:

- Understanding the Trust Model

- Permanent Funds

- Challenges from New Uses and Demands

- Implications for Federal Land Transfer

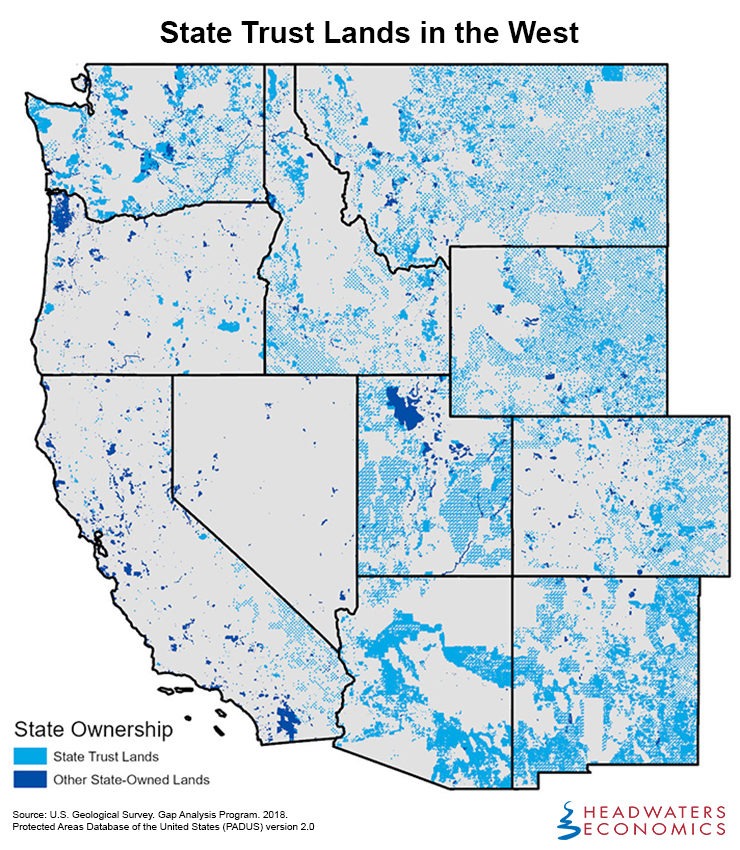

State trust lands were granted by the U.S. Congress to states as they entered the Union for the specific purpose of generating revenue to fund public institutions, primarily public schools. Today, state trust lands comprise about 51 million acres, mostly in the western United States. As the nation’s economy and values change, the public is placing new demands on state trust lands.

Trust Lands Must Generate Revenue

State trust land managers have an obligation to maximize revenue from state trust lands. However, activities traditionally conducted on state lands such as grazing, timber harvest, oil and gas drilling, and mining may not maximize revenues. In some instances, state trust managers have difficulty maximizing revenue because of cultural, political, and lobbying pressure to limit competition and maintain below-market leasing rates for traditional users.

New Trust Land Uses are Emerging

In a changing economy and society, state trust lands are providing new types of value. Some of these, such as leases for wind and solar power generation, easily fit into the commercial leasing model of traditional activities. However, many new uses—such as conservation and recreation—are valuable to the public, but difficult for managers to monetize for beneficiaries.

These new aesthetic, recreation, and environmental values are increasingly important to the public. In some instances, states have been able to capture some value from these activities for beneficiaries. For example, some states charge recreation fees for non-consumptive activities such as hiking, biking, or bird-watching. However, these fees generate minimal revenue. In Montana, for example, less than 1% of trust lands revenue comes from these fees.

Alternatively, sometimes conservationists or recreationists have been able to enter the private leasing market to bid competitively against loggers or ranchers. For example, Idaho now has a specific type of lease designed for conservation. However, nontraditional users competing in the leasing market is rare. They often face opposition from traditional users and there are sometimes large transaction costs associated with changing the land use. Most importantly, it is usually difficult or impossible to exclude others from reaping the benefits of recreation or conservation leases, so lessees cannot capture monetary value from their land.

Finally, in some cases, states own extremely large parcels that allow them to develop selected areas for which they can charge more when they also set aside nearby parcels for conservation or outdoor recreation. However, because of the way state trust lands were granted, most state trust parcels are small and scattered, precluding this option.

Beyond Private Markets

Private markets can only rarely provide for new public values such as conservation, aesthetic, and cultural uses on state trust lands. To provide these values, state governments have intervened in a variety of ways, including subsidizing public values on trust lands, purchasing trust lands with taxpayer dollars, or simply changing the rules to allow land to be managed for outcomes beyond revenue maximization.

States subsidize public value on trust lands by, for example, fighting wildfire or managing for endangered species habitat with funds outside the trust land budget. States also sometimes purchase lands identified as highly valuable for conservation. For example, since 1989, Washington has spent about $800 million to conserve more than 111,000 acres and lease 5,000 acres of state trust lands.

It is also possible to change the fiduciary trust mandate to accommodate public values on trust lands. In Colorado, voters interested in a broader suite of values provided by state lands simply changed the rules. Voters passed a constitutional amendment that changed the focus of the fiduciary trust away from generating the “maximum possible amount” to “providing for prudent management” of the trust lands.

These actions indicate important new directions for state trust land management that should inform ongoing debates about trust lands in a changing economy.

State Trust Lands in Transition

This report is in a four-part series seeking to better understand state trust lands in the western economy and landscape. The series includes:

- Understanding the Trust Model

- Permanent Funds

- Challenges from New Uses and Demands

- Implications for Federal Land Transfer

Series Contributors

Chelsea Lidell

Chelsea was a 2019 Public Lands Fellow at Headwaters Economics.

Mark Haggerty

Mark is a Researcher and Policy Analyst with Headwaters Economics.

Cover photo of state trust land sign courtesy Tom Lane – High Country News.