State Trust Lands in Transition

This report is in a four-part series seeking to better understand state trust lands in the western economy and landscape. The series includes:

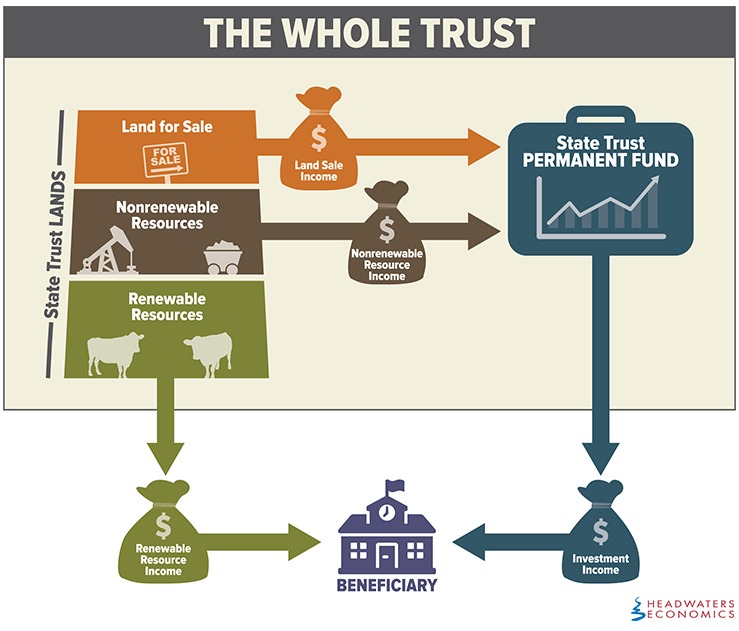

State trusts have two parts: 1) state trust lands that were granted to states by the U.S. Congress when the states entered the Union; and 2) a permanent financial fund. Together these comprise the “whole trust,” which is managed to generate revenue for schools and other public institutions. The majority of states that have retained these trusts and created a permanent fund are in the West. State trust lands amount to about 51 million acres today.

The Trust Model

The value of a state trust—whether held in land or in money (that is, a permanent fund)—must be maintained in perpetuity. States receive revenues from state trust lands in several ways:

To maintain the value of the whole trust for future generations, nonrenewable resource income and revenue from land sales must be deposited into permanent funds.

Permanent Fund Policies Become Politicized

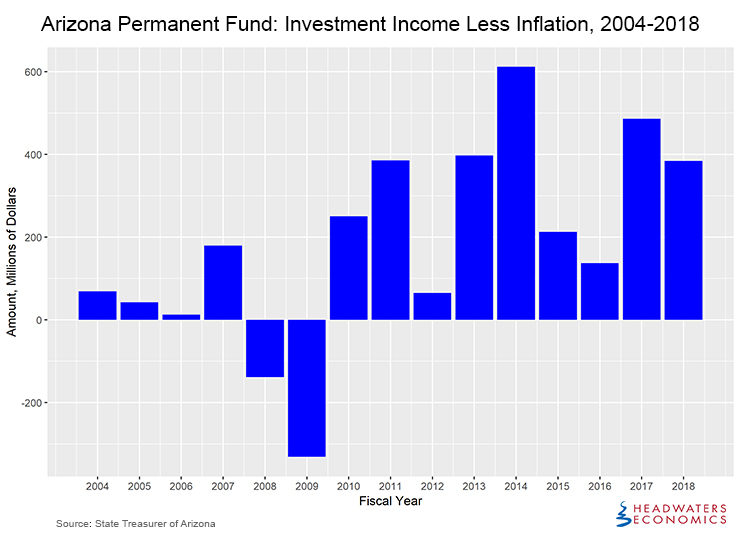

To optimize earnings on permanent fund principals, states have revised investment policies in the past three decades to invest more heavily in the stock market. Many states have increased their rates of return; however, revenue streams have become much more volatile.

For example, in the 20 years since Arizona approved permanent fund investment in stocks, it has seen great volatility in year-to-year investment returns, as the graph below shows.

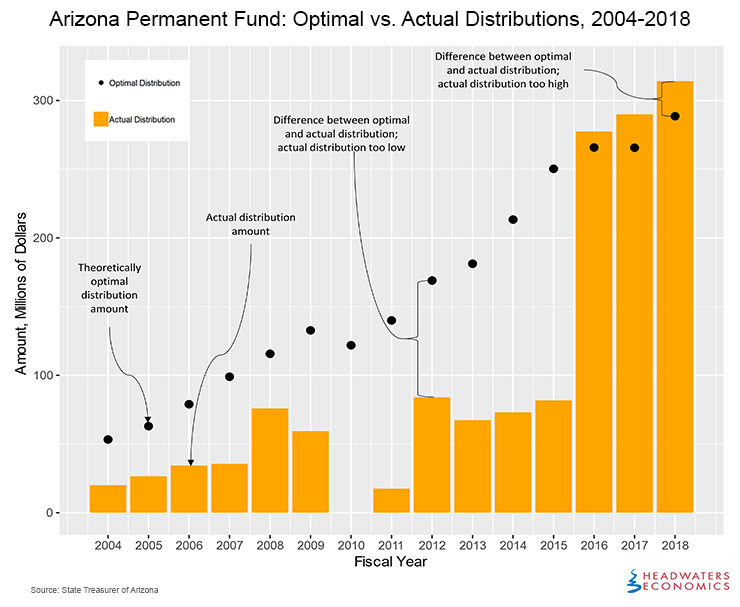

To complicate matters, states have modified their distribution policies—that is, the percentage of the permanent fund revenue that is paid out to schools and public institutions versus the percentage that is reinvested. Distribution policies are often highly political.

Recent permanent fund policy changes in several states will have serious consequences for education and land management. We have seen four types of mismanagement:

For example, from 2004 to 2015 Arizona distributed less than optimal amounts, prioritizing future beneficiaries over current beneficiaries. In recent years, however, Arizona has distributed more than optimal amounts, prioritizing current beneficiaries over future beneficiaries and shrinking the whole trust.

New Mexico and Colorado have similar policies that are shrinking the value of the whole trust. Utah is currently suffering the consequences of past policies that diminished the whole trust value.

Permanency at Risk

Our research indicates that some states are failing to maintain the value of the whole trust: Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado are over-spending from permanent funds to pay for services and avoid raising taxes; Colorado is also spending nonrenewable revenue on current needs instead of investing it in permanent funds. By treating nonrenewable revenue and the permanent fund as disposable income, the long-term value of the trust is reduced.

As the whole trust diminishes, it provides less support for education, which incentivizes further sales of land and nonrenewable resources to bridge the funding gap.

States Should Manage for Sustainability

States need an optimal distribution benchmark with legal safeguards so they can maintain the value of the whole trust for future generations. Recommendations for more sustainable management include:

Regardless of what policy or process a state chooses, the key evaluation metric is that the value of the whole trust is maintained.

State Trust Lands in Transition

This report is in a four-part series seeking to better understand state trust lands in the western economy and landscape. The series includes:

Series Contributors

Chelsea Lidell

Chelsea was a 2019 Public Lands Fellow at Headwaters Economics.

Mark Haggerty

Mark is a Researcher and Policy Analyst with Headwaters Economics.

Featured image of state trust land sign courtesy Tom Lane – High Country News.