Cloud Peak Energy, Inc, a large producer of federal coal in Wyoming, is concerned that the proposed changes will have a big effect on its profitability.

That’s prompted Peabody Energy, also a large producer of federal coal, to respond that the likely outcome of proposed reforms on the industry will be small, if any.

Currently, ONRR uses five benchmarks to audit weather the price reported by a mine for royalty valuation is reflective of competitive market sales. These five benchmarks, in theory, should all come up with the same answer.

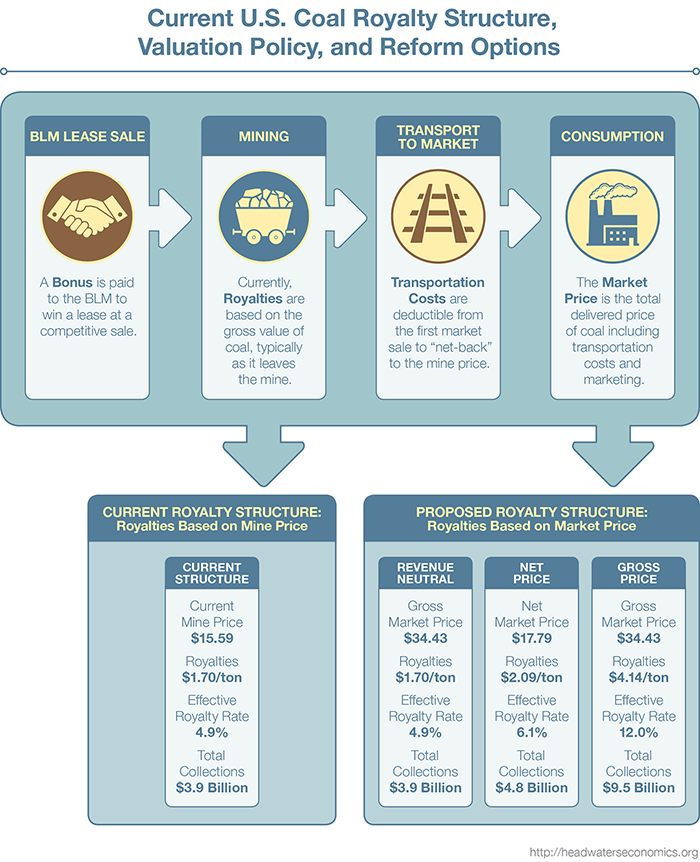

The proposed federal rule would eliminate the five benchmarks in favor of a single valuation method—ONRR would use the first arm’s-length sale, net of transportation costs, as the basis for royalty valuation.

Cloud Peak is correct that this change could advantage non-affiliated brokers, hurting Cloud Peak’s logistics business. Effectively, mines and affiliated brokers would have to pay royalties on the full value of their final sales to consumers. Unaffiliated brokers, on the other hand, could avoid paying royalties on their sales to domestic and export markets.

Peabody also is correct because in many cases the change would not alter the current valuation methods. And in instances where companies used affiliated brokers to avoid royalty payments, the coal market may simply restructure so that non-affiliated brokers play a larger role. The end result for the taxpayer (and the price of coal overall) would be little to no change.

The potential that the proposed rulemaking could advantage some and not others in the coal market is an argument for why ONRR should consider going further than the current proposal: changing the point of valuation from the mine to the market.

This would capture the value of export sales in all instances—whether the mine markets coal directly or sells to affiliated or unaffiliated brokers. Such a change would close the affiliated sales loophole without causing new market distortions.

Our estimate is that using market prices instead of mine prices to value coal could add a maximum of $0.18 cents per ton on average for all coal sales from federal land (about one half of one percent of average delivered prices).

Some of this amount will come out of the brokers margin, and some will be shifted forward as higher prices. The increased cost of coal deliveries to the domestic and export market is likely to be modest—too small to warrant any excitement on Wall Street.