Among the list of things that Congress seems incapable of doing these days is to pass legislation, even bipartisan legislation, that would save money and prevent disasters. The Wildfire Disaster Funding Act of 2014 is another one of those bills that simply stalled. It would have created an emergency fund that would allow us to treat wildfires like hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornadoes.

This was a missed opportunity for two reasons; one obvious, and one more surprising.

The bill would eliminate the perverse practice of “fire borrowing,” where agencies like the Forest Service take money designed for one purpose, like active management to restore land or reduce fuels, and divert it for suppression.

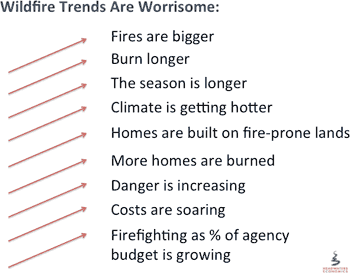

This means that as federal firefighting costs continue to escalate–from $1 billion per year in the 1990s to $3 billion per year in the 2000s—less money is available to do the very things that would help reduce the severity of the fires.

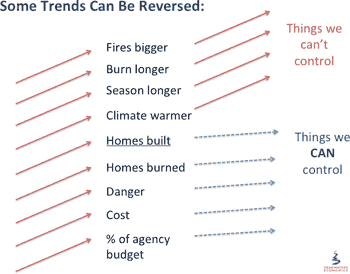

The second missed opportunity is subtler but also easily understood. If firefighting were funded separately, the Forest Service would have more leeway to address long-term trends, even reversing some. The most promising place is to address future home building on dangerous, fire-prone lands.

Our research indicates that at least one-third of the firefighting bill goes to defend private homes. Others, like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, put the estimate higher, at 50 to 95 percent. In some fires, agencies spend $200,000 to $400,000 per home.

Since 1990, the number of homes destroyed by wildfire has tripled, yet development continues. Also, since 1990, 60% of new homes in the U.S. have been built in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI), the private land next to public forests.

Defending these homes is too often also tragic. In the last thirty years firefighter fatalities have doubled.

If wildland firefighting were treated like other disasters and funded separately, Forest Service could take a portion of it’s $2.2 billion fire budget (say, a modest 1% or $22 million) and direct that to communities in the form of grants and technical assistance in land use planning.

Taking a lesson from floodplain management, there could be a community rating system, that will direct more assistance to those that do the most to help themselves through zoning, fire risk mapping, transferable development rights programs, incentives for cluster development, open space programs, and other planning tools.

Escalating firefighting costs will not be controlled—even if funded through a separate fund—unless we find the right incentives to steer future development away from lands where it costs lives and billions of dollars of taxpayer money to defend private homes.