Walter E. Hecox, who received his PhD from Syracuse University (1969), is Professor Emeritus of Economics in the Environmental Program, Colorado College, Colorado Springs, Colorado. He is also Senior Program Advisor, El Pomar Foundation’s Pikes Peak Recreation and Tourism Heritage Series. Professor Hecox has managed and performed research for the Grand Canyon Trust; Colorado Department of Natural Resources Executive Director’s Office; U.S. Dept. of Energy; World Bank; U.S. Agency for International Development; Southern African Development Coordination Conference; U.S. Military Academy; Ford Foundation; and the National Science Foundation. He founded and served for a decade as faculty advisor to the Colorado College State of the Rockies Project, supervising over 45 research studies on the eight-state Rockies region in demographics, energy, land management, climate change, and amenity economies.

The eight-state Rockies region is world-renowned for spectacular scenery, environment, and recreation. Decades of European settlement, coming on top of centuries of indigenous Native American habitation, have transformed the ways humans use the region’s landscape. And yet prior human development and current uses largely conform to natural patterns of land, water, air, flora and fauna: all more intertwined and fragile than residents largely understand and support. Thus, regional concepts and perspectives are vital to understanding how natural resources serve as a foundation for economy and quality of life. An understanding of the role nature and resources play is central to preparing for the future of the Rockies region. It is a future that continues to be grounded in nature and resources even as the extraction phase gives way to a natural amenity phase in the region’s economy and quality of life.

The Rockies Setting

The Rocky Mountains or “Rockies” as a geographical feature has integrity as a physiographic region connected by its Continental Divide spine running along its mountainous crest from the Canadian border in the north to Mexico in the south. Geographers describe it as a mountain range forming the cordilleran backbone of the great upland system that dominates the western North American continent. It is a distance of some 3,000 miles (4,800 km). In places the system is 300 or more miles wide.

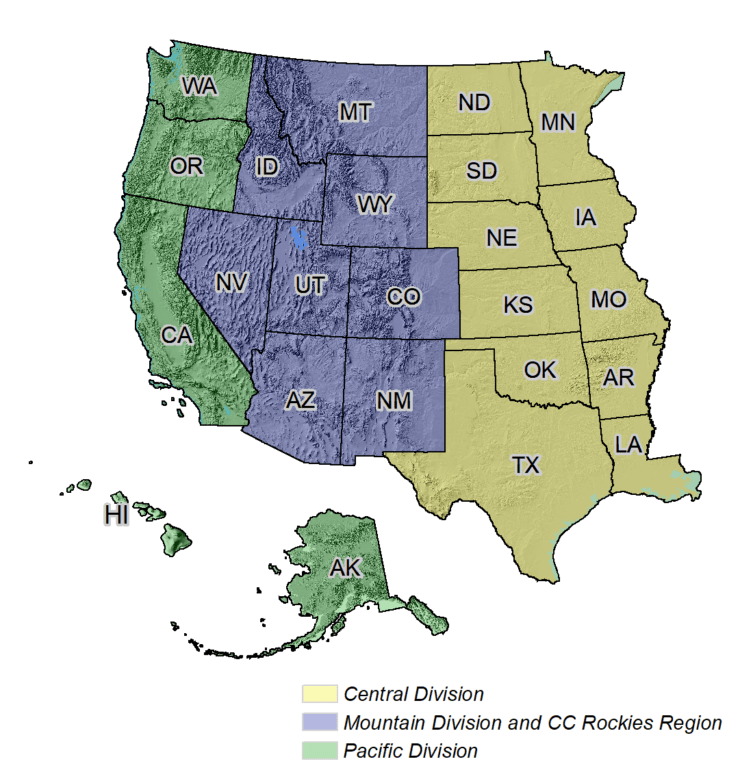

In demographic terms the eight states embracing the Rockies form the U.S. Census Bureau’s Rockies Division (Map 1). It comprises 863,242 square miles and 24% of the U.S. landmass compared to 7.3% of the 2016 population in the United States.

Map 1: Census divisions for Pacific, Central, and Mountain regions. (Source: Headwaters Economics, Economic Profile

System.)

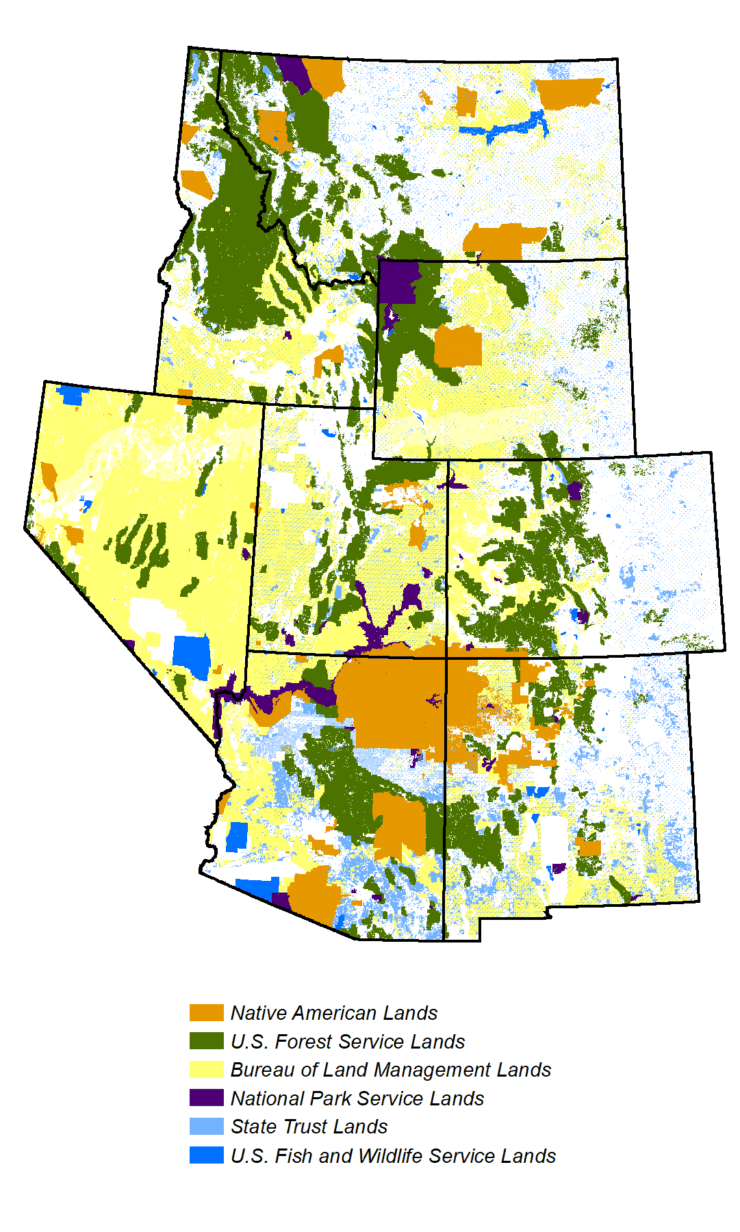

In land management terms, 48% of the Rockies comprise federal public lands versus 28% for the United States; sparse settlement leads to 21 people per square mile versus 80 for the United States (Map 2). The region’s defining features include spectacular natural beauty, harsh climate and soil conditions, and huge tracts of sparsely settled lands juxtaposed with rapidly growing urban areas. These vast open spaces continue to capture the imagination of residents and visitors alike while offering up profound challenges. These include a suggested promise of rugged individualism; the reality of recreation and solitude that appears endless but in fact is limited and fragile; limits to extracting vital natural resources in the future without damaging the land and environment as in the past; and the need to form sustainable patterns of human habitation and resource management to match the grandeur of the scenery.

Map 2: Federally protected lands in the Rockies (Source: Headwaters Economics, Economic Profile System.)

At first glance, the view millions receive as they fly over the Rockies region on their way to other destinations is a vast area that appears to be a huge empty quarter. Clusters of dense population make the region 1.4% developed (urban or built-up land, including rural transportation corridors), confirming what our eyes told us from afar. Looking more closely, patterns emerge of dense agricultural activity, roads, and clusters of people in towns, cities, and large metropolitan areas. Water defines life in the region, historically along streams and in the rich river bottom areas, and increasingly today in areas where water has been pumped from the ground and diverted on the surface to feed agricultural, municipal, and industrial demands. Equally defining of the Rockies is the abundance of land publicly owned and managed in a stunning array of types, from Bureau of Land Management grazing lands, to forests controlled by the U.S. Forest Service, to the “crown jewels” of nature and culture under the National Park Service, and to formal or informal wilderness designation. Some people chafe under “absentee” management from Washington, DC, while others look to this same management to preserve the public domain and its health for current and future generations.

So we have a region that is vast, rugged, and at the same time fragile, varied in the density and pattern of population and economic activity, alluring to waves of tourists and migrants wishing to partake of its openness and beauty. For decades, since the 1870s and early attempts to measure economic activity in the region, boom-bust cycles of human habitation and economic activity have made life in the Rockies challenging and uncertain. More fundamental forces have also been at work, creating a transition from resource extraction to amenity-based uses and values for nature.

A review of how the Rockies have changed over past decades, when joined to a snapshot of the entire region as it looks today, helps us understand why.

Regionalism is Always Important

Regional concepts and perspectives are vital to understanding how the Rockies region is defined. The area has evolved over centuries of human development, and must prepare for a future that continues to be grounded in natural resources even as their role in the economy and quality of life are dramatically changing. In contrast to the Rockies’ natural resource extraction era, a broader “natural amenities” perspective is essential, one that comprehensively includes land, fauna and flora, water, and air. Thus, our understanding of the “services” of nature has evolved beyond extraction and cultivation into the concept of value derived from intact nature. Our understanding of natural resource systems in the region extends over large areas that are inextricably linked, such as entire watersheds and river basins, migrating herds of wildlife, ranges of mountains, and grasslands and forested areas connected by the increasing spread of insects and disease. All of the Rockies region shares climate change forces that ignore political and economic boundaries. The Rockies region thus enters a new era with forces binding together lands, people, and economic systems. In short, Rockies natural resources, once balanced and managed by nature, now require ever more sophisticated human management if the region’s spectacular ambience is to be passed along to our children. And we must remember: The “rugged” Rockies are largely a misnomer, for the region shares high altitude, aridity, intertwined riparian systems, and vegetation that are prone to abuse and destruction.

The earlier nineteenth-century premise of an “empty quarter” across the American frontier underscored a time when government encouragement sent European explorers and settlers flowing westward, seeking mineral, forest, and agricultural acreage often available through mining claims and Homestead Act filings. Initially those failing or exhausting the land’s productivity could then move on when productive acres were exhausted. After a few short decades, emptiness has given way too often to crowding, a “tragedy of the commons” situation where many uses and users often compete and damage the shared commons and often have external third-party spatial and temporal impacts on others. Thus mine tailings of a century ago continue to leak toxic waste fouling land and water; acres previously farmed have often been abandoned as the associated water rights have been severed to higher monetary value municipal and industrial sectors. Human settlements, once sparse and dispersed, are giving way to large municipalities and associated dispersed habitation in the wildland-urban interface (WUI). Wildlife systems once balanced by predator-prey relationships have been severely disrupted by predator destruction, which has spawned overgrown and unhealthy herds that now require increasing natural balance management through human hunting and culling. A century of “all forest fires out by dawn tomorrow” U.S. Forest Service management philosophy, combined with major reductions in logging and vegetation management, have now created too often a perfect storm of dense, aged, diseased stands of timber in a situation where higher aridity and drought cycles bring forth vast wildfire burns that destroy natural and human assets.

Complex forces impacting the Rockies can be shortened into a near-poetic cadence: Wildfires burn, bugs eat trees, water supplies dwindle, snow packs shrink, tourists overwhelm recreation, WUI developments pull people into danger, dream houses torch, urban proximity to nature chokes on archaic roads, tame and diseased wildlife invade gardens and parks, land management budgets are diverted to fighting fires.

The Rockies Then

Natural resources and environment historically have both determined and shaped human habitation and economic activity in the Rockies region. Starting in the mid-1800s, a pattern of explorers, and then prospectors, followed by European settlers began to take advantage of the region’s vast natural wealth, seemingly there “for the taking.” In later decades, into and through the twentieth century, the numbers of people and sophistication of technology allowed for ever more significant extraction and use of land, water, minerals, and flora as well as fauna to support patterns of economic activity and European settlement.

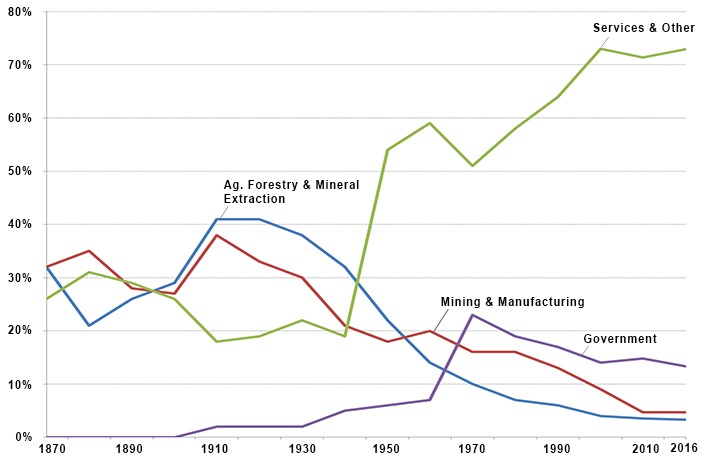

A paucity of information makes it difficult to draw a complete picture of ways by which the land initially supported European settlement in the Rockies. Trends in four broad economic sectors of employment add to our understanding of how historic forces helped shape today’s Rockies region. Figure1 traces in rough terms the roles of agriculture, forestry and fishing, starting at 32% of employment in 1870, peaking at four out of 10 jobs from 1910 to 1940, and then steadily decreasing to 10% in 1970 and down to 4% from 2000 to 2016. Manufacturing activity in the Rockies has always been modest, with the heavy industry located outside the region and transportation bringing finished manufactured goods to the Rockies. Mining and modest manufacturing started out at 32% from 1870 to 1890, then leveled off at three in 10 jobs from 1900 to 1930, followed by manufacturing gradually becoming more important than mining, with both at 20% from 1940 to 1960, after which a steep decline put such mining and manufacturing jobs at 15% from 1970 to 1990, and decreasing to 5% in the first part of the twenty-first century.

Figure 1. Rockies region employment trends in agriculture, forestry, mineral extraction; mining and manufacturing; services and other; government. (Source: U.S Bureau of the Census and Historic Atlas)

Services (broadly defined as jobs that support other sectors) helped the Rockies economy grow and diversify, standing at 26-30% of jobs from 1870 to 1900, decreasing with a fall-off in mining and modest manufacturing activity until 1950, after which services rose by decade to 64% in 1990 and 73% by 2016. Government employment is informative given the common misconception that “government bureaucrats” are heavily represented in the Rockies. Such jobs were not even measured until 1910 when it stood at 2-7% from 1920 to 1960, followed by a near quadrupling by 1970, levelling off at 19% by 1990, and falling to 13% by 2016.

Care must be taken in looking at these decade-by-decade patterns: while cultivation and extraction of natural resources have dramatically declined, nature’s “amenity” characteristics have increasingly become the foundation for the Rockies’ population growth and increasingly service-based economy. Thus, nature’s role in the Rockies economy toward the end of the twentieth century and first two decades of the twenty-first century are implicit but no less important!

The Rockies Now

Our summary review since the decade of the 1870s has demonstrated the gradual movement of the Rockies economy from primarily land and natural resource extraction-based activities such as farming and forestry to increasingly amenity-based economic forces including recreation and retirement. What is fundamental about this shift is not that natural resources are less important because they are not extracted as in the past, but that natural resources themselves are still the foundation and driver for economic activity. A snapshot of the current Rockies economy, measured by modern U.S. Census Bureau categories of employment (Table 1) supports the phenomenon of continued natural resource dependence, radically altered toward more importance of natural amenities, recreation, and tourism and less extractive activities. Four employment dimensions from 2001 to 2016 stand out:

- Farm, forestry, fishing and mining (including fossil fuels) employment are 3.3% in both 2001 and 2016;

- Manufacturing employment was 6.6% in 2001 and declined to 4.7% by 2016;

- Arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodations, and food employment was 11.3% in 2001 and grew to 11.5% by 2016;

- Government employment was 14.5% in 2001 and declined to 13.3% by 2016.

| 2001 Shares | 2016 Shares | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Employment (number of jobs) | 100.0% | 100% |

| Non-services related | 17.5% | 13.8% |

| Farm | 1.8% | 1.5% |

| Forestry, fishing, & ag. services | 0.5% | 0.4% |

| Mining (including fossil fuels) | 1.0% | 1.3% |

| Construction | 7.6% | 5.8% |

| Manufacturing | 6.6% | 4.7% |

| Services related | 67.7% | 72.9% |

| Utilities | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Wholesale trade | 3.4% | 3.2% |

| Retail trade | 11.2% | 10.4% |

| Transportation and warehousing | 2.9% | 3.3% |

| Information | 2.5% | 1.7% |

| Finance and insurance | 4.9% | 5.4% |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 4.1% | 5.6% |

| Professional and technical services | 6.2% | 7.1% |

| Management of companies | 0.8% | 1.1% |

| Administrative and waste services | 6.3% | 6.3% |

| Educational services | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| Health care and social assistance | 7.7% | 9.8% |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 2.2% | 2.4% |

| Accommodation and food services | 9.0% | 9.1% |

| Other services, except public admin. | 4.8% | 5.2% |

| Government | 14.5% | 13.3% |

These results reinforce the idea that natural amenities are an important ingredient in helping communities and states attract businesses, workers, and investment. While public lands are associated with travel and tourism activities—which are important in their own right—research increasingly shows that these activities are only one part of a larger amenity economy that is an important driver of economic growth across the West.

The Rockies Tomorrow: Natural Resource Theory Evolving

Natural resource economics is a long-standing part of economic theory, dealing with the supply, demand, and allocation of the Earth’s natural resources. Resource economists study interactions between economic and natural systems with the goal of developing a sustainable and efficient economy. Public lands in the Rockies are central to such issues. For non-renewable resources, historic and current extraction of minerals and petroleum occur at rates feasible technically and financially. Results are not only substantial income-wealth benefits, but also third-party impacts called “external costs” such as air and water discharges and toxic residue. For renewable resources, such as silviculture, grazing, and water collection-diversion, again technological and financial feasibility are essential and third party impacts occur on riparian habitat, fauna-flora, and down-stream water availability. Designing optimum exhaustion for non-renewables and sustained yield for renewables ideally must also reflect levels of technology and globalization. Management of natural resources is thus complex and needs to draw from different disciplines within the natural and social sciences connected to broad areas of earth science, natural ecosystems, and human socioeconomic systems.

Contemporary natural resource theory increasingly encompasses the concept of “amenity” values from new uses of traditional natural resources and environment. Technology has replaced mineral content in much production and introduced alternative energy sources beyond fossil fuels, while globalization has often brought alternative sources of processed goods at competitive prices, thus reducing competitiveness of Rockies region products. The forces of climate change, aridity, and rising average temperatures complicate resource usage further. Meanwhile affluence and travel mobility have created new uses and benefits from “nature left in its own conditions.” Housing in wildland-urban interfaces, organized recreation at resorts, dispersed hiking and camping, tourism seeking beautiful vistas, hunting and fishing—all of these and more value “nature” more in its intact locations and condition than if it were processed and extracted. Nature by its mere existence increasingly contributes to overall social welfare and quality of life levels even as we threaten to “love nature to death.”

To understand the Rockies as a holistic region requires perspectives drawn from geography, history, and ecology as well as natural resource and regional economics. The abundance of public lands as well as interconnected natural systems, from hydrology to climate to fauna and flora, mean that a broad theory of how economy and ecology interact is necessary. The major change in how nature serves as a foundation for economy and quality of life leads us to the overarching concept of “amenity economics” for modern management. Helpful readings span academic fields and approaches.

Suggested Reading

To understand the Rockies as a holistic region requires perspectives drawn from geography, history, and ecology as well as natural resource and regional economics. The abundance of public lands as well as interconnected natural systems, from hydrology to climate to fauna and flora, mean that a broad theory of how economy and ecology interact is necessary. The major change in how nature serves as a foundation for economy and quality of life leads us to the overarching concept of “amenity economics” for modern management. Helpful readings span academic fields and approaches.

- Armstrong, Harvey. 2000. Regional Economics and Policy. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Baron, Jill. 2002. Rocky Mountain Futures – An Ecological Perspective. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Canning, Richard. 2007. The Rockies – A Natural History. Vancouver, BC: Greystone Books.

- Green, Gary, Steven Deller, and David Marcouiller, eds. 2006. Amenities and Rural Development. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Howe, Jim. 1997. Balancing Nature and Commerce in Gateway Communities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Katz, Bruce, ed. 2000. Reflections on Regionalism. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- McKinney, Matthew and William Harmon. 2004. The Western Confluence: A Guide to Governing Natural Resources. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Nie, Martin. 2008. The Governance of Western Public Lands. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

- Power, Thomas. 1988. The Economic Pursuit of Quality. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Power, Thomas. 1996. Lost Landscapes and Failed Economies: A Search for A Value of Place. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Rasker, Ray. 1992. The Wealth of Nature: New Economic Realities in the Yellowstone Region. Washington, DC: The Wilderness Society.

- Worster, Donald. 1998. Nature’s Economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.