Editor’s Note: A similar version of this blog first appeared on Meeting of the Minds.

Urban trail efforts increasingly are focusing on providing equitable access to trails. Trails and parks can create substantial benefits for public health, property values, and quality of life.

Unfortunately, in many communities these resources are inequitably distributed. They can be less abundant in poorer neighborhoods with a larger share of minority residents, which can be exacerbated by a history of segregation in public places and lack of racial and ethnic representation in trail and conservation organizations. In addition, in more urban areas, historically minority or low-income areas tend to be more densely developed, leaving less space for building new parks or trails.

The benefit of parks and trails is greatest for those who live closest to these resources, and a disparity in access can have significant health, social, and economic implications, while also exacerbating environmental justice concerns in communities.

The benefit of parks and trails is greatest for those who live closest to these resources, and a disparity in access can have significant health, social, and economic implications, while also exacerbating environmental justice concerns in communities.

More and more, cities are improving access by incorporating trails and pathways as part of their planning, development, and revitalization standards—moving beyond trails as a recreational amenity and incorporating trails as critical contributors to goals in public health, climate resilience, and transportation.

Improving park and trail access also is an important tool to help revitalize urban neighborhoods, and relatively new tools like crowdsourcing can help cities collect more accurate and extensive trail user data when measuring performance and future needs.

City Trails: Improving Equitable Access

Communities can take a variety of steps and approaches to improve trail access. A study of parks in southern California urban centers, for example, found that parks are used less in high-poverty areas than in low-poverty areas, driven partly by safety concerns; parks in high-poverty areas have, on average, eight fewer staff than parks in low-poverty areas.

In Los Angeles County, California, a study that follows a large sample of children over time demonstrated that children who live a walkable distance from parks are much less likely to be obese or overweight. Health benefits can be achieved through formal parks and recreation programs, but also through accessible green space or other small, informal places that encourage play. For instance, children who lived within 500 meters of a park had a significantly lower body mass index (BMI) at age 18, with larger effects for boys than for girls.

How communities assess inequities in access to green space also is important. An equity-mapping analysis found that low-income and concentrated poverty areas have significantly less access to park resources—and that creative strategies to utilize nontraditional public spaces such as schoolyards and vacant lots will be necessary because there is very little available park space in the most underserved neighborhoods.

How communities assess inequities in access to green space also is important. An equity-mapping analysis found that low-income and concentrated poverty areas have significantly less access to park resources—and that creative strategies to utilize nontraditional public spaces such as schoolyards and vacant lots will be necessary because there is very little available park space in the most underserved neighborhoods.

In Taos, New Mexico, lower trail use among Hispanic and low-income residents is likely due to differences in access, not because these residents do not want to use trails. Low-income residents with a park or trail within a 10-minute walk of their houses were 50 percent more likely to have used trails during the previous year.

Trails Can Help Revitalize Neighborhoods

Accessible trails also are likely to play an important role in any neighborhood revitalization effort. Last year Curbed published a series of case-studies showing how nine linear parks have helped city neighborhoods by improving transportation and economic connections within cities.

Improving trail access also can contribute to economic development. Planning lessons for creating more vibrant neighborhoods include making them more walkable by slowing traffic, having shorter blocks, increasing density, and developing commercial nodes. According to Ellen Dunham-Jones, co-author of “Retrofitting Suburbia,” planners have been utilizing these and other “walkable communities” principles to help revitalize more than 750 neighborhoods across the country.

Earlier this year, Business Insider ran an article discussing how cities that have removed roads—in favor of trails, parks, or housing—have saved money and brought greater vitality to neighborhoods while also increasing real estate values.

The economic impact of proposed trails can be monetized—in terms of public health and safety, environmental sustainability, and economic benefits—to provide community leaders with additional potential trade-offs from a trail. Such an analysis provides a greater understanding of how likely trail benefits (such as improved access, safety, public health, property values, and economic activity) can offset construction and maintenance costs of a project.

Crowdsourced Data: Who Is Accessing Trails?

Community leaders, elected officials, trail users, and others working on increasing trail access are utilizing “crowdsourced” data from social media and GPS-enabled fitness tracking apps to provide new insights into trail user behavior and values.

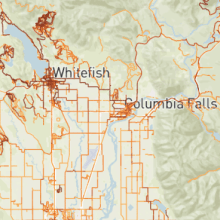

An analysis for the area around Whitefish, Montana shows how Strava Metro data can be combined with in-person surveys and trail counters to estimate recreational trail use by type (local or tourist) and by activity (pedestrian or bike). The study found that the Whitefish Trail contributes $6.4 million in annual spending by visitors who come to enjoy the trail and by locals who purchase or rent outdoor gear at local stores. Spending by visitors who use the Whitefish Trail translates to 68 additional jobs and $1.9 million in labor income in Whitefish.

Using Strava data allows researchers to generate comprehensive estimates of trail use for entire trail segments rather than only at certain points where trail counters were deployed. This approach is replicable in other communities and is substantially less expensive than estimating trail use and benefits using traditional analyses based entirely on local survey data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported that crowdsourced data, such as Strava, can accurately reflect activities like trail use, especially in areas with higher population density.

The CDC report concluded: “User-generated, GPS-tracked data sources might provide critical information regarding active transportation to local health and transportation officials as a complement to traditional active transportation surveillance systems; these data might inform investments in active transportation programs and infrastructure.”

More communities are utilizing trails to pursue overlapping goals for social justice and equity, public health, transportation, and economic development. To reach these goals—and help build public support—new crowdsourced data and research can help deepen our understanding of trail users, expand the multiple benefits of trails to neighborhoods, and provide equitable access to trails and their benefits.