This page summarizes two longer reports: “A Comparative Analysis of the Economies of Peer Counties with National Parks and Recreation Areas to Penobscot and Piscataquis Counties, Maine” and “The Regional Economy of Penobscot and Piscataquis Counties, Maine and a Potential National Park and Recreation Area.”

[Note: This region was designated the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in 2016.]

Summary Findings

Elliotsville Plantation, Inc. is considering a donation of land to create a National Park and recreation area, along with an endowment for maintenance in the Katahdin Region of Maine. The lands in question are on the eastern edge of Baxter State Park along the East Branch of the Penobscot River. Headwaters Economics conducted this economic analysis under the assumption that there would be up to 150,000 acres of land donated to the National Park Service, of which 75,000 acres would be in a National Park (NP) and 75,000 acres would be in a National Recreation Area (NRA).

A review of other areas similar to the two-county study region — Penobscot and Piscataquis counties — in northern Maine that already have a National Park and NRA combination found that these areas consistently outperform Penobscot and Piscataquis counties (as well as the U.S. as a whole) across a range of economic performance measures. These regions have capitalized on visitation, non-local spending, and related job impacts to grow and diversify their economies, including sectors that pay above average wages.

This assessment of the potential costs and benefits of a new National Park and recreation area found little evidence of an economic downside, including to the forest products industry. On the other hand, there is evidence pointing to economic opportunities: new travel and tourism activity; the ability to attract people, retirees, and businesses across a range of sectors; economic growth including higher-wage jobs; and increases in non-labor sources of income.

The Katahdin Region is growing, though there are significant differences between the more populous south and the north, and between communities. Most recent population and economic growth is found in the south, along with higher earnings and lower unemployment. The north has slower or negative economic growth, depending on the community, and residents are older and have less formal education.

The economy of the two-county region has shifted dramatically in recent decades. Forest products industry jobs have declined steadily since the mid-1990s. At the same time, a modern services economy, including higher-wage services in sectors like health care and professional and technical services, has become the dominant form of economic activity. In addition, non-labor sources of income–closely related to growing investment income and an aging population–are now the largest sources of personal income in the region.

Land is an important asset–but by no means the only asset–in a broader economic development strategy. Research suggests that communities near protected areas such as National Parks and NRAs are likely to realize greater economic benefits when they also invest in other advantages such as education and infrastructure.

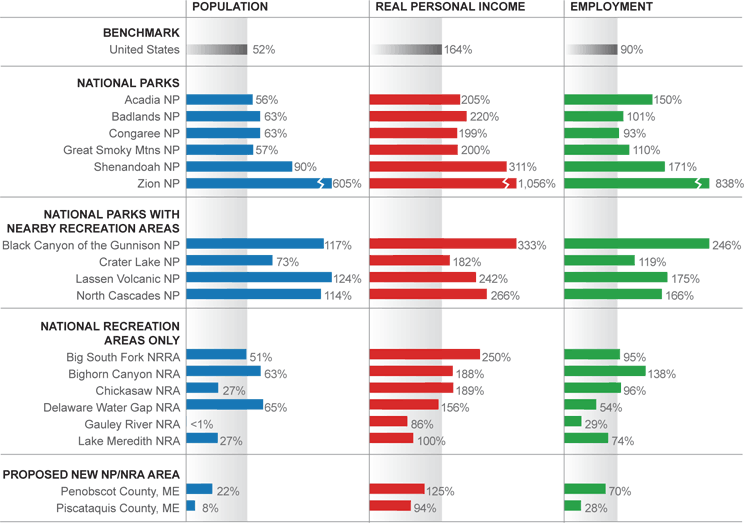

Similar Regions with National Parks and Recreation Areas Outperform the U.S. and the Katahdin Region

We studied the economic performance of local communities adjacent to 16 National Parks and NRAs across the country based on similarities to the two-county region in Maine.

Economic Performance: In every case the economies of peer regions with National Parks alone, or with National Parks that also have nearby NRAs, grew faster than the U.S. as a whole and faster than Penobscot and Piscataquis counties from 1970 to 2010. This was not the case for peer regions with NRAs alone, where the data show a more uneven picture of economic growth.

Diversifying Economies: The areas with National Parks alone, or National Parks with nearby NRAs, generally have diversified their economies into a range of services industries, including higher-wage sectors. Peers with NRAs alone were less successful at making a transition to a modern services economy, which may explain their difficulty sustaining growth over time.

Potential Job Creation: Recreational visitation and visitor spending make important economic contributions to National Park and NRA regions, supporting local businesses and private sector jobs as well as agency jobs and payrolls. The potential jobs impact of a new National Park and recreation area ranges from slightly more than 1,000 jobs (based on a comparison to peers and including NPS jobs) to just more than 450 jobs (based on capturing a share of Acadia National Park visitation and excluding NPS jobs).

National Park and NRA Peers, Percent Change in Population, Real Personal Income, and Employment, 1970 to 2010

Costs and Benefits of a New National Park and Recreation Area

Timber Industry: If 150,000 acres of private land east of Baxter State Park were harvested for timber, few jobs would be created. The land is 80 percent forested (120,000 acres), capable of producing, at most, 120,000 tons per year of green fiber. Harvesting this amount of green fiber annually on a sustainable basis could employ up to 21 workers to bring the wood to mills. It is unlikely any new mill jobs would be created because the additional 120,000 tons of wood represents less than one percent of Maine’s annual timber utilization. When including indirect jobs, annual overall timber operations could potentially yield a total of 50 local jobs.

Tax Revenues: Penobscot County would receive more taxes and the state marginally less revenue if a National Park and recreation area were established. Private property taxes would no longer accrue to local and state governments if the land were conveyed to the National Park Service. Instead, the U.S. Department of the Interior would make Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT). Assuming Penobscot County receives PILT payments from Unorganized Territory lands, it would collect an additional $326,126 per year, about two percent of the county budget.

Visitors and Spending: A new National Park and NRA would create improved recreational amenities, such as paved scenic drives, visitor centers, retail shops, restaurants, and overnight accommodations (in contrast to the camping-centric experience at Baxter State Park) and would likely draw more visitors and capture more spending. It would also highlight the spectacular nature of these resources and give visitors a reason to consider adding a northern destination to coastal trips centered on Acadia National Park. For perspective, if a new National Park and recreation area captured 15 percent of Acadia visitor traffic, this could reasonably be expected to create slightly more than 450 private sector jobs locally.

Recreation Impacts: While the NRA component would allow hunting, fishing, snowmobiling and other activities traditionally enjoyed by area residents, the National Park would support a number of other activities–such as scenic driving, bird watching, berry picking, hiking, camping, white water rafting, kayaking, canoeing, mountain biking, mountaineering, and cross country and backcountry skiing. An examination of National Park and NRA peers found that visitor spending and park employment created an average of more than 1,000 private and public sector jobs.

Land Protection: The land under consideration for a possible National Park and recreation area contains a wide diversity of flora and fauna, as well as rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds. Their protection could help safeguard important wildlife habitat, water bodies, and late successional forests.

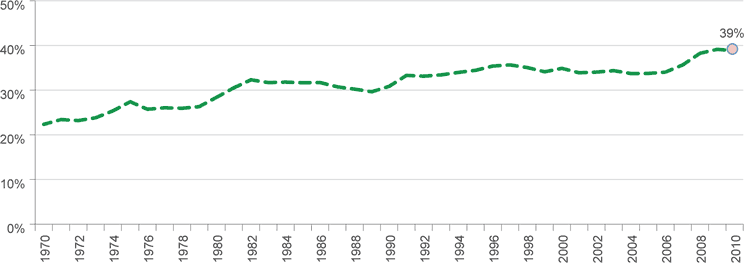

Diversification: Proximity to a highly visible protected area could help gateway communities like Millinocket attract younger workers, families, and small businesses in a range of regionally growing sectors, such as health care and professional and technical services. Gateway communities also could more easily draw retiring Baby Boomers and non-labor income, which totaled $2.2 billion, or 39 percent of total personal income, in the two-county area in 2010.

The Regional Economy Has Grown Over the Long-Term

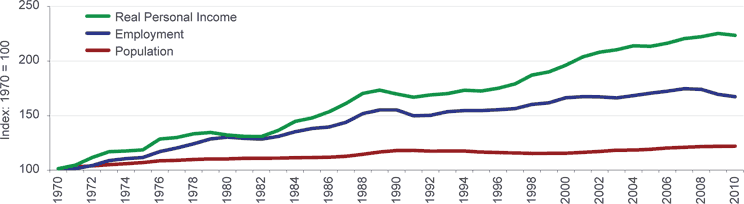

Population, Employment, and Real Personal Income, Indexed, 2-County Region

In the study area, population, employment, and real personal income (i.e., adjusted for inflation) all grew from 1970 to 2010. Population grew by 21 percent, employment by 66 percent, and real personal income by 122 percent in this time period. In addition, per capita income rose by 86 percent from 1970 to 2010, as personal income growth outpaced population gains.

The Structure of the Economy Has Changed Dramatically

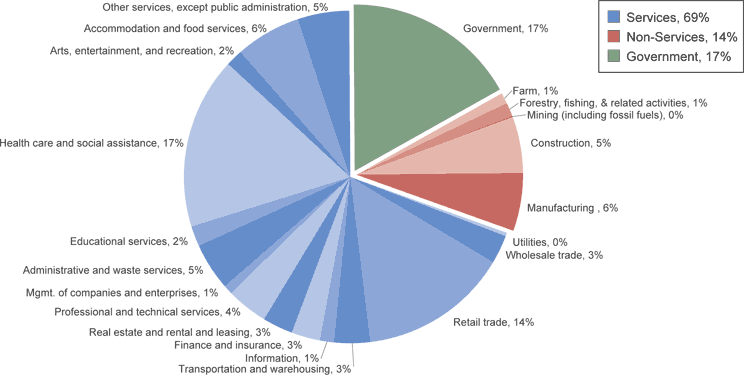

Employment, Services and Non-Services Industries, 2-County Region, 2010

The region has shifted from a resource-based economy, including timber, agriculture, construction and manufacturing, to one based predominantly on services-related sectors, such as health care, education, professional and technical services (e.g., engineers, architects), tourism, and real estate. Services industries (69% of total jobs) in the two-county region employed six times as many people as non-services industries (14% of total jobs) in 2010.

The shift to a services economy does not necessarily mean a move to low-wage jobs. For example, in 2011 there were 1,324 wood and paper manufacturing jobs in the two-county region, compared to 16,463 jobs in health care. Health wages are generally on par with the forest products industry in Penobscot County while slightly lower in Piscataquis County.

As personal income has grown in the region, non-labor sources of income–mainly consisting of investment and retirement income–have increased substantially. From 2000 to 2010 in the two-county region non-labor sources of income grew by $475 million, in real terms, and accounted for 67 percent of net new personal income growth.

Non-Labor Income Share of Total Personal Income, 2-County Region

By 2010, non-labor sources of income in the two-county region accounted for $2.2 billion, or 39 percent of total personal income. To put this in perspective, lumber and wood products manufacturing employment generated $193 million and health care employment $301 million in personal income in 2010.

Significant Differences Remain Between the North and South of Penobscot county

| North Penobscot County | South Penobscot County | |

|---|---|---|

| Population (2010) | 20,784 | 132,150 |

| Population (2000) | 20,956 | 123,963 |

| Population Change (2000-2010) | -172 | 8,187 |

| Population Percent Change (2000-2010) | -1% | 7% |

| % People Below Poverty (2010) | 19% | 15% |

| % Families below poverty (2010) | 15% | 9% |

| % of Households Receiving Earnings,by Source (2010): | ||

| Labor Earnings | 64% | 77% |

| Social Security | 43% | 29% |

| Retirement Income | 21% | 17% |

| Supplemental Security Income | 6% | 6% |

| Cash Public Assistance Income | 8% | 6% |

| Food Stamp/SNAP | 19% | 15% |

| % with Bachelors Degree or Higher (2010) | 12% | 25% |

While already six times more populous, the southern portion of Penobscot County, which includes Bangor, is growing while the more sparsely populated north is losing population. Residents in the south have completed higher levels of formal education and the area has lower poverty rates than the north. In the south, a higher percentage of families derive their income from labor earnings, while in the north a higher percentage derive income from Social Security and Retirement, consistent with the area’s relatively older population.

From 2000 to 2010, in-migration accounted for 70 percent of Bangor’s population growth. Young people continue to move to Bangor (718 new 18-34 year olds from 2000 to 2010), but the most quickly expanding demographic is Baby Boomers (2,041 new 45-64 olds from 2000 to 2010).

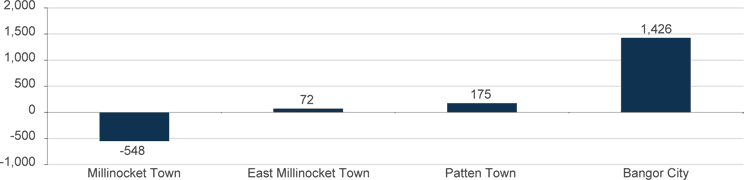

Population Change by Town, 2000 to 2010

From 2000 to 2010, the growth of towns within Penobscot County varied widely. Most population gains took place in Bangor (+1,426), while losses occurred in Millinocket (-548) over this time period. Unemployment is higher in northern towns. Millinocket and East Millinocket, for example, had unemployment rates of 17 percent and 16 percent, respectively, in June of 2012.

Specific Economic Sectors: Timber and Tourism

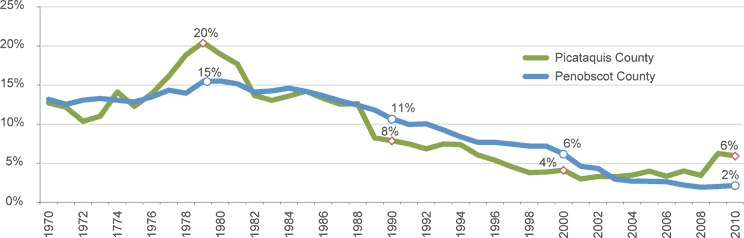

Timber: Since peaking in the 1970s, the significance of the forest products industry has declined in importance relative to the region’s overall economy, while harvest levels have fluctuated but remain relatively constant.

Personal Income from Wood Products Manufacturing (Lumber, Paper, Pulp) as a Percent of Total Personal Income, Penobscot and Piscataquis Counties

Personal income earned in wood products and paper manufacturing in the two-county region declined from 16 percent of total personal income in 1979 to three percent in 2010. Piscataquis County remained more dependent on the forest products industry (6% of total personal income) than Penobscot County (2% of total personal income) in 2010.

Tourism: Outdoor recreation is big business in Maine. The Outdoor Industry Association estimated that in 2006 the outdoor recreation economy in Maine supported 48,000 jobs, generated $210 million in annual state tax revenue, and produced almost $3 billion annually in retail sales and services, accounting for seven percent of gross state product.

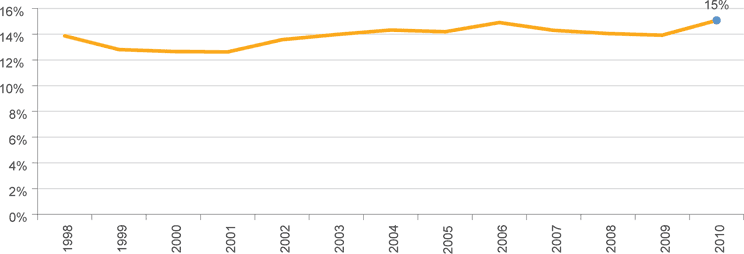

Percent of Total Private Employment in Industries that Include Travel and Tourism, 2-County Region

From 1998 to 2010, travel and tourism related industries held steady in the two-county region at roughly 15 percent of total private jobs, accounting for 9,353 private sector jobs in 2010.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following analysts and economists for their review of earlier drafts and for their helpful and insightful comments: Richard Barringer, Emeritus Professor, University of Southern Maine; Charles Colgan, Professor of Public Policy and Management, University of Southern Maine; Rob Lilieholm, Associate Professor of Forest Policy, School of Forest Resources, University of Maine; and David Vail, Emeritus Professor of Economics, Bowdoin College. We also are grateful for comments and suggestions provided by Sewall Company, Old Town, Maine. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of Headwaters Economics.