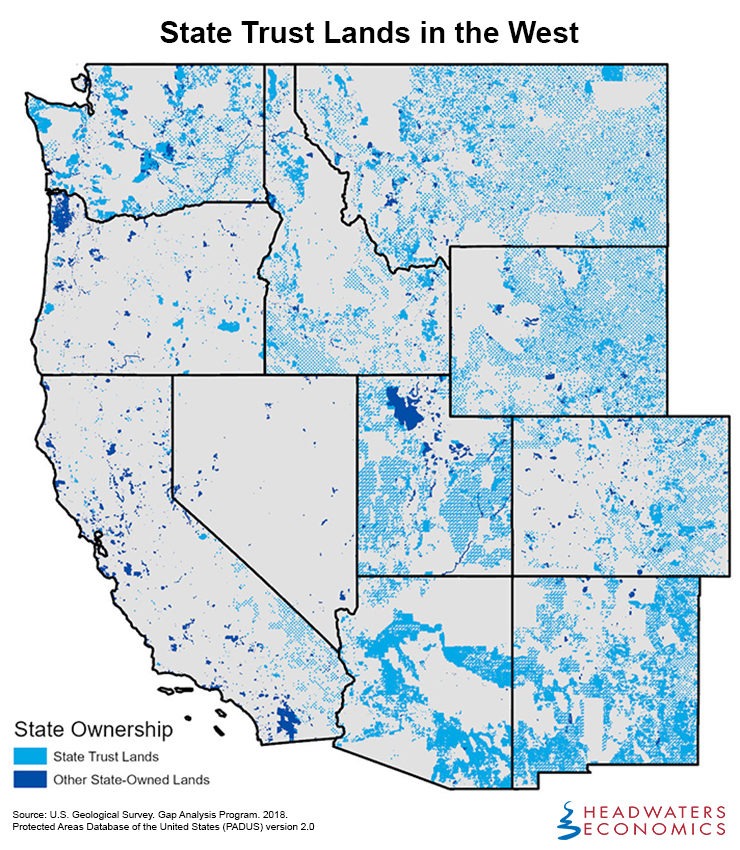

- State trust lands comprise a significant portion of the West—one in every 20 acres. They are not “public lands” in the traditional sense because public access is generally restricted.

- States are obligated to maximize revenue from trust lands for the benefit public institutions.

- States typically generate revenue by leasing state trust lands for natural resource extraction and commercial development.

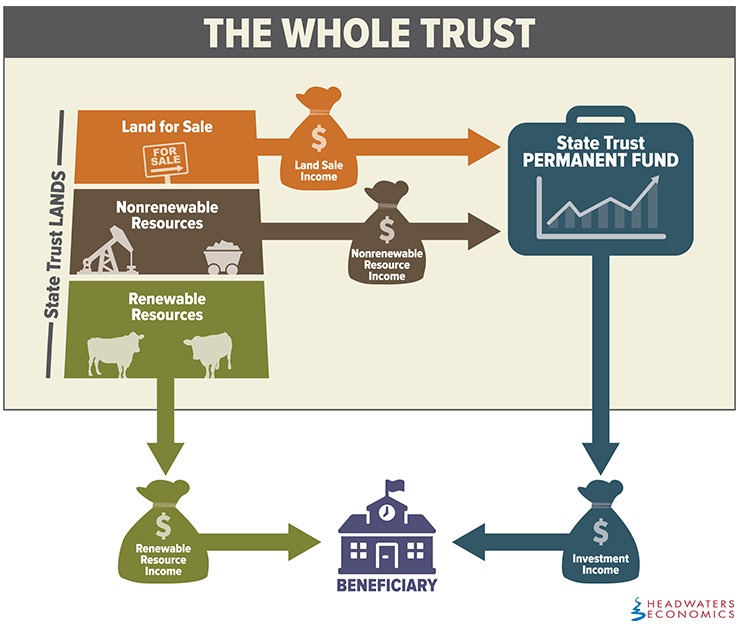

- States created permanent funds to save revenue and generate investment income, protecting the value of the whole trust in perpetuity.

State Trust Lands in Transition

This report is in a four-part series seeking to better understand state trust lands in the western economy and landscape. The series includes:

- Understanding the Trust Model

- Permanent Funds

- Challenges from New Uses and Demands

- Implications for Federal Land Transfer

State trust lands make up one of every 20 acres in the western United States and in 2018 generated more than $1.6 billion in gross revenue from renewable natural resource activities, commercial development, land sales, and nonrenewable resource extraction.

Despite their extensive footprint on the western landscape, state lands remain relatively unacknowledged in debates about public lands. This is in large part because state trust lands are not, in fact, public lands as they are commonly understood. The trust lands were granted to states as they entered the Union for the specific and narrow purpose of generating revenue to fund public institutions, primarily public schools.

The Trust Model

Two principles of state trust land management are central to understanding its purpose and uses:

- Fiduciary Trust: The fiduciary trust obligates trust land managers to generate revenue on behalf of a beneficiary—public schools and other public institutions. Public access, recreational use, environmental quality, or community economic benefits are not permitted unless they maximize income from the trust land resource.

- Permanence: The value of the original trust assets granted to states must be held in perpetuity to benefit current and future generations. In practice, that means the trust lands are not sold, but are retained by states and managed to generate revenue via renewable resource activities such as grazing and timber management. Or, if state trust managers do sell land or nonrenewable trust assets (such as fossil fuels or minerals), the proceeds of these sales must be placed into a permanent fund to generate revenue for current and future beneficiaries.

States receive revenues from state trusts in two primary ways:

- Annual, renewable income. Trust lands are managed for renewable natural resource and commercial activities that include grazing and agricultural leases, timber sales, and commercial property leases. Revenue from renewable activity is distributed to beneficiaries annually.

- One-time, nonrenewable income. Income earned from the sale of trust lands and nonrenewable resources is transferred to the permanent fund. The corpus of the permanent fund is invested in financial markets to earn revenue that is distributed to beneficiaries annually.

Fragmented Ownership of State Trust Lands

The map below shows the fragmented pattern of state trust lands in the West. States were typically granted two sections (one square mile each) within each township (consisting of 36 sections). Widely dispersed land ownership limits management options and, in some cases, reduces potential for generating revenue.

Unique Trust Model

State trust lands are not “public lands” in the traditional sense because public access to them is generally restricted. Trust lands were granted to states for the specific and narrow purpose of generating revenue for public institutions, primarily public schools.

Each state pursues slightly different mechanisms for generating revenue, from passive leasing to riskier investments in public-private partnerships and land development. Revenues from trust lands can swing widely from year to year based on leasing and royalty rates and the prices and production volumes of timber, oil, gas, minerals, and other resources.

State Trust Permanent Funds

State trust permanent funds are invested in financial markets to generate investment income that is distributed to beneficiaries. In most states, permanent funds are managed by state investment councils that are housed in the state treasurer’s office or another state agency, but not within the trust land management agency.

Strategies for investment and distribution vary widely from state to state. In recent years, more sophisticated and aggressive investment policies in some states have increased investment income substantially. Revenues are increasingly taking the form of capital gains instead of dividends and interest. Year-to-year revenues can be much more volatile. (Read more about permanent funds.)

Different Approaches Among States

States have taken strikingly different approaches to meeting the fiduciary duty to maximize revenue for current and future generations. This report and companion reports in the State Trust Lands in Transition series show that the obligation to maximize revenue and protect the value of the whole trust is often difficult to achieve in practice. State trust managers are often pressured to prioritize the needs of current beneficiaries over those of future generations, to make decisions that benefit long-time lessees (rent-seeking behavior), and to meet the needs and wants of stakeholders who are not direct beneficiaries.

The way that these pressures on state trust lands and permanent funds are resolved will affect current and future beneficiaries and shape debates about the future of state trust lands, federal public lands, state fiscal policy, and the ongoing economic transition in the West.

State Trust Lands in Transition

This report is in a four-part series seeking to better understand state trust lands in the western economy and landscape. The series includes:

- Understanding the Trust Model

- Permanent Funds

- Challenges from New Uses and Demands

- Implications for Federal Land Transfer

Series Contributors

Mark Haggerty

Mark is a Researcher and Policy Analyst with Headwaters Economics.

Chelsea Lidell

Chelsea was a 2019 Public Lands Fellow at Headwaters Economics.

Cover photo of state trust land sign courtesy Tom Lane – High Country News.