Paul Lorah, PhD, is a geographer at the University of Saint Thomas. He grew up in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and returns as often as possible. Paul served on the Board of Trustees for the Minnesota Nature Conservancy. Along with his students, he has written grants funding over $150,000 in conservation projects.

Our landscapes are getting pretty tame. More than 380,000 miles of roads fragment our national forests, and tallgrass prairie covers less than 4% of its former range. Today, even sea creatures in the deepest ocean trenches test positive for high levels of persistent organic pollutants. If you really want to experience a pristine ecosystem, you may have to venture to Lake Whillans, where bacteria survive undisturbed (until recently) in a two-meter-thick lens of water hidden under roughly 2,500 feet of Antarctic ice.

We are getting pretty tame too. As the concept of play shifts from an outdoor to an indoor activity, kids are spending less time in natural environments. Less time building forts and more time breathing recirculated air and looking at screens lit by artificial light. This probably is not making them happier. A recent study of over a million American students found that kids who spend more time immersed in social media have lower levels of psychological well-being. All this, despite studies showing that connecting with nature has positive effects on health, including stress reduction and weight loss. And perhaps the rest of us should not be too smug? How many mountain bikers can name as many species of trees as they can types of beer?

John Muir was far too poetic to use a phrase like nature deficit disorder, but he recognized the danger:

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.” – John Muir, Our National Parks (1901)

Connecting with nature can bring joy, exuberance, exhilaration, and perspective. Too few wildlands remain, and they should be enjoyed by more of us. I think we need protected public lands like wilderness areas and national parks more than ever. They may not be truly wild, but they are still shaped by natural processes, and they are open to all of us.

There are also good reasons to think protected lands are only going to increase in value. In the 1960s, John Krutilla noted that wilderness areas are rare, unique, and fragile. Once degraded, the supply of wildlands decreases, as they are difficult to restore. He also thought that the number of people valuing wilderness would increase because of growth in population, recreation, and tourism. (Despite our iPhone addiction, the outdoor recreation industry remains large – generating more than $400 billion in 2018). The implication is that increasing demand for a shrinking resource should promote more investment in wilderness.

Not everyone agrees that protecting wilderness, roadless areas, national parks, and national monuments makes good economic sense. Some view protected public lands as symbols of outside control. They want public lands to serve as warehouses of raw materials, and fear that environmental protection locks up valuable resources and undermines the foundation of rural economies by cutting off access to timber, minerals, energy, and grazing lands. This “jobs versus the environment” perspective may be a view through the rearview mirror, yet it still resonates in places left behind by the economic transition from extraction to amenity economies.

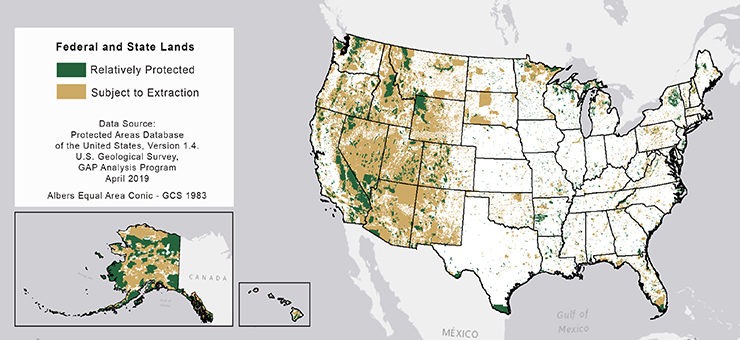

Land management policies have the power to reshape the economies, cultures, and landscapes of the rural West. This makes balancing demands for resource extraction, recreation, and environmental protection extremely difficult. Conflict between those who want to protect public lands and those who want access to resources can be intense, partly because so much is at stake. Federal and state agencies manage approximately half of the land in the 11 western states, and therefore control landscapes surrounding many rural communities (Map 1). Wilderness areas alone cover 110,025,309 acres—approximately the combined size of Germany and Austria.

Map 1: Relatively protected state and federal lands and lands subject to extraction.

Much of the debate over our public lands is fueled by emotion, tribal affiliation, and political calculation. Still: I think the Old West view that conservation and the presence of protected lands undermines economic growth has two key weaknesses:

The first weakness is that extractive industries no longer drive prosperity. A wide range of factors (including mechanization, economic diversification, environmental policies, global competition, a declining resource base, and rapid growth in more competitive economic sectors) has undermined the relative importance of natural resource industries. One sign of this decline is that America now has more parking lot attendants than coal miners. The simple fact is that the relative contribution of extractive industries to rural western economies is small and has been declining for decades. The vast majority of new jobs in the West are in services, and in the rural West, non-labor income is nearly an order of magnitude larger than income generated by mining, oil, gas, and timber.

The second weakness is based on a long-running natural experiment. Protected public lands are unevenly distributed throughout the West. The result is a wide range of variation from one county to the next: some are dominated by protected lands, while others are dominated by lands open to resource extraction. Over time, these management differences should influence their development paths. So if the “jobs versus the environment” view is correct, counties containing high levels of wilderness, national parks, and national monuments should be at a competitive disadvantage. Similarly, if extraction drives growth, then counties containing public lands that are open to grazing, logging, mining, and energy extraction should do relatively well.

This is just not the case. A wide range of studies shows that counties containing land protected for conservation and recreation outperform counties containing land managed for commodity production. Study areas vary, as do variables used to measure economic security, but the results are consistent. One careful study of the 284 non-metro counties in the West found that an increase of 10,000 acres of protected public lands was associated with an increase of per capita income of $436. You have to work fairly hard to link protected lands to negative economic outcomes. (Hint: Gerrymander the study area in ways that allow you to compare rural wilderness counties to a group of counties containing cities and suburbs. Then focus on the size of the economy. It also helps to exclude variables like property values, education levels, and retirement and investment income.)

Why do many public lands counties do relatively well? Environmental amenities provide more stability and long-term economic benefits than commodity resources. Some communities still suffer from a legacy of lost landscapes and failed economies, where a narrow reliance on extraction creates a “jobs first – then migration” boom and bust cycle. In contrast, the lure of natural beauty, clean air, and spectacular opportunities for outdoor recreation attracts tourists. Tourism can bring a number of benefits, including support for new restaurants, shops, and recreational opportunities. When people visit, some decide to stay, including relatively wealthy retirees who bring money earned elsewhere (dividends, interest, rent, and Social Security payments) and spend it in their new communities. Increasing numbers of tourists and retirees promote growth in industries ranging from health care to construction. The result can be economic diversification and increased investments in transportation, including regional airports.

This happens in concert with an influx of amenity migrants. Many are relatively educated and increasingly mobile knowledge workers who find protected public lands more attractive than jobs in mines, natural gas fields, or timber mills. They move to public lands counties and then either look for jobs, create jobs, telecommute, or live off investments—a “migration first – then jobs” strategy.

As it gets easier to work in communities near wilderness and national parks, amenity migration should continue to increase, especially public lands counties with access to nearby population centers and regional airports. Not everyone focuses on the fact that knowledge-based production allows people to work on mountaintops instead of centralized manufacturing centers, but we all know that you can conduct global business in a rural setting. If you have the money, you do not have to sacrifice much in the way of comfort, either. Amazon delivers, Netflix is ubiquitous, and many resort towns have world-class doctors, financial advisors, brew pubs, and bookstores.

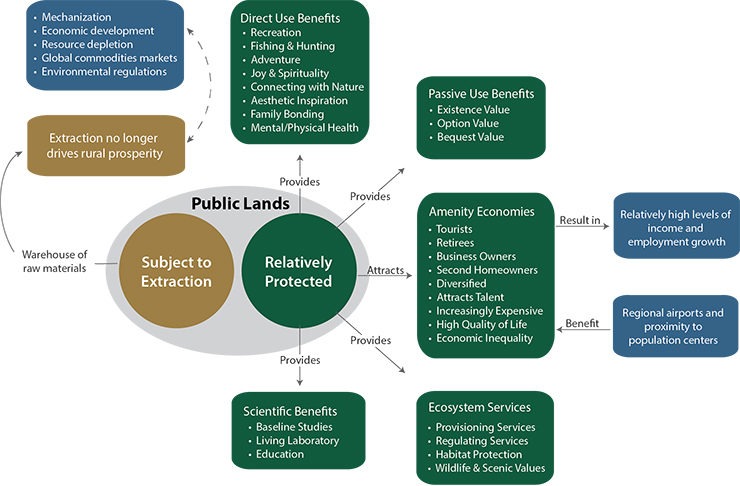

As the West shifts from extraction to amenity economies, our debate over public lands should evolve. The “jobs verses the environment” argument makes little sense. Protected lands improve our quality of life and they support employment in large and growing economic sectors. There are also far more economic reasons to protect wildlands than I have covered in this short essay, including direct use values, ecosystem services, scientific benefits, existence value, bequest value, option value… (the list goes on: see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Benefits of protected lands.

Our last great wildlands are threatened, increasingly scarce, and essential to our wellbeing. Our climate is changing and we need bigger islands of habitat connected by migration corridors to promote resilience and limit the damage. Our grandchildren deserve better than what we are leaving them.

All of this does not change the fact that some communities are being left behind. Most of us understand that economies thrive when they attract talent, focus on innovation, and diversify, but that knowledge does not help isolated communities lacking environmental amenities. I think that this means that we need to think carefully about the “jobs in extraction versus jobs in services” question—especially if we use forest products, eat beef, or rely on minerals and fuels extracted from public lands. Yes, we should conserve and recycle; yes, we should transition from fossil fuels to renewables. But do we really want to eliminate production on public lands and instead rely on global commodity markets to supply raw materials and energy? Instead, I think we should consider the value of traditional ways of life, of self sufficiency, and of the limited economic prospects facing isolated counties without environmental amenities. If we want electric vehicles, we have to ask ourselves whether mining lithium in Bolivia is less environmentally destructive than mining it in Nevada.

Another challenge we face is that environmental amenities, creative class workers, increasing property values, and downhill skiing all sound pretty great unless you have to struggle to support your family. There is something to the joke that billionaires are pushing millionaires out of Aspen, or the observation that the bigger the mountain home, the less time it is occupied. The connection between environmental protection and economic growth is hopeful in many ways, but as we work to protect wildlands we also need to consider ways to ensure amenity-led growth benefits a wider range of people.

“What we risk creating is a theme park alternative reality for those who have the money to purchase entrance. Around this Rocky Mountain theme park will sprawl a growing buffer zone of the working poor. In the last century, the Western Slope functioned as a resource colony for timber and mining interests. Those scars will be with us for generations. We cannot afford to stand by now as the culture of a leisure colony… takes its place.” – J. Francis Stafford

I am hopeful that many ways forward involve a “jobs and jobs and environment” solution. The Nature Conservancy’s grass-banking programs support neighboring ranchers, build community, and improve prairie habitat. Careful logging practices can reduce fire risk, improve habitat in second-growth forests, and generate local employment. A few ranchers in western Colorado are building a network of modernist tiny homes to rent to mountain bikers. It is also easy to imagine kids in both the old and new West becoming interested in restoration ecology and the many hours of work required to start restoring degraded landscapes. We should all put down our iPhones, get outside, and get to work.

Suggested Reading

- Booth, Douglas E. 1999. Spatial Patterns in the Economic Development of the Mountain West. Growth and Change 30 (3): 384-405.

- Bowker, J.M., H.K. Cordell, and N.C. Poudyal. 2014. Valuing Values: A History of Wilderness Economics. International Journal of Wilderness 20(2): 26-33.

- Díaz, Sandra, Unai Pascual, Marie Stenseke, Berta Martín-López, Robert T. Watson, Zsolt Molnár, Rosemary Hill, Kai MA Chan, Ivar A. Baste, and Kate A. Brauman. 2018. Assessing Nature’s Contributions to People. Science 359(6373): 270-272.

- Gosnell, Hannah and Jesse Abrams. 2011. Amenity Migration: Diverse Conceptualizations of Drivers, Socioeconomic Dimensions, and Emerging Challenges. GeoJournal 76(4): 303-322.

- Hansen, Andrew J., Ray Rasker, Bruce Maxwell, Jay J. Rotella, Jerry D. Johnson, Andrea Wright Parmenter, Ute Langner, Warren B. Cohen, Rick L. Lawrence, and Matthew PV Kraska. 2002. Ecological Causes and Consequences of Demographic Change in the New West: As Natural Amenities Attract People and Commerce to the Rural West, the Resulting Land-use Changes Threaten Biodiversity, Even in Protected Areas, and Challenge Efforts to Sustain Local Communities and Ecosystems. AIBS Bulletin 52(2): 151-162.

- Holmes, Thomas P., J.M. Bowker, Jeffrey Englin, Evan Hjerpe, John B. Loomis, Spencer Phillips, and Robert Richardson. 2015. A Synthesis of the Economic Values of Wilderness. Journal of Forestry 114(3): 320-328.

- Krutilla, John V. 1967. Conservation Reconsidered. The American Economic Review 57(4): 777-786.

- McGranahan, David A. 1999. Natural Amenities Drive Rural Population Change. Agricultural Economics Report No. 33955. Washington, DC: USDA Economic Research Service.

- Nelson, Peter B., Lise Nelson, and Laurie Trautman. 2014. Linked Migration and Labor Market Flexibility in the Rural Amenity Destinations in the United States. Journal of Rural Studies 36: 121-136.

- Phillips, Spencer. 2004. Windfalls for Wilderness: Land Protection and Land Value in the Green Mountains. PhD Dissertation. Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

- Power, Thomas Michael. 1996. Lost Landscapes and Failed Economies: The Search for a Value of Place. Vol. 38. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Rasker, Ray. 2006. An Exploration into the Economic Impact of Industrial Development Versus Conservation on Western Public Lands. Society and Natural Resources 19(3): 191-207.

- Rasker, Ray and Dennis Glick. 1994. Footloose Entrepreneurs-Pioneers of the New West. Illahee-Journal for the Northwest Environment 10(1): 34-43.

- Rasker, Ray, Patricia H. Gude, and Mark Delorey. 2013. The Effect of Protected Federal Lands on Economic Prosperity in the Non-Metropolitan West. Journal of Regional Analysis & Policy 43(2): 110.

- Rudzitis, Gundars. 1999. Amenities increasingly draw people to the rural west. Rural Development Perspectives 14(2): 9-13.

- Rudzitis, Gundars. 1993. Nonmetropolitan Geography: Migration, Sense of Place, and the American West. Urban Geography 14(6): 574-585.