- The Tongass National Forest has made no meaningful shift in its budget and staff allocations since announcing the Transition Framework in 2010.

- The Tongass National Forest continues to invest disproportionately (34-45% of its budget) in a timber industry that provides relatively few jobs (1% private employment) while neglecting more economically important industries to the region such as tourism and fishing (24%).

- The Tongass National Forest remains predominantly focused on old growth harvests (87% of proposed sales) at a significant cost to U.S. taxpayers (more than $100 million).

In 2010 the Forest Service announced a new direction for the Tongass National Forest. Called the “Transition Framework,” the Forest Service proposed a “new path forward in the region that enhances economic opportunities to communities while conserving the Tongass National Forest.”

Four years since this commitment, it is fair to ask if a transition is in fact occurring, and whether it is improving economic opportunities for communities in southeast Alaska. To understand if change is taking place, this report examines the Tongass National Forest budget and staffing, as well as the economy of southeast Alaska and proposed timber sales.

We worked with Ross Gorte, Ph.D., to produce the report. Gorte, a retired Senior Policy Analyst at the Congressional Research Service, is now an Affiliate Research Professor at the University of New Hampshire.

Detailed Findings

Tongass National Forest Has Failed to Shift Resources from Timber Program

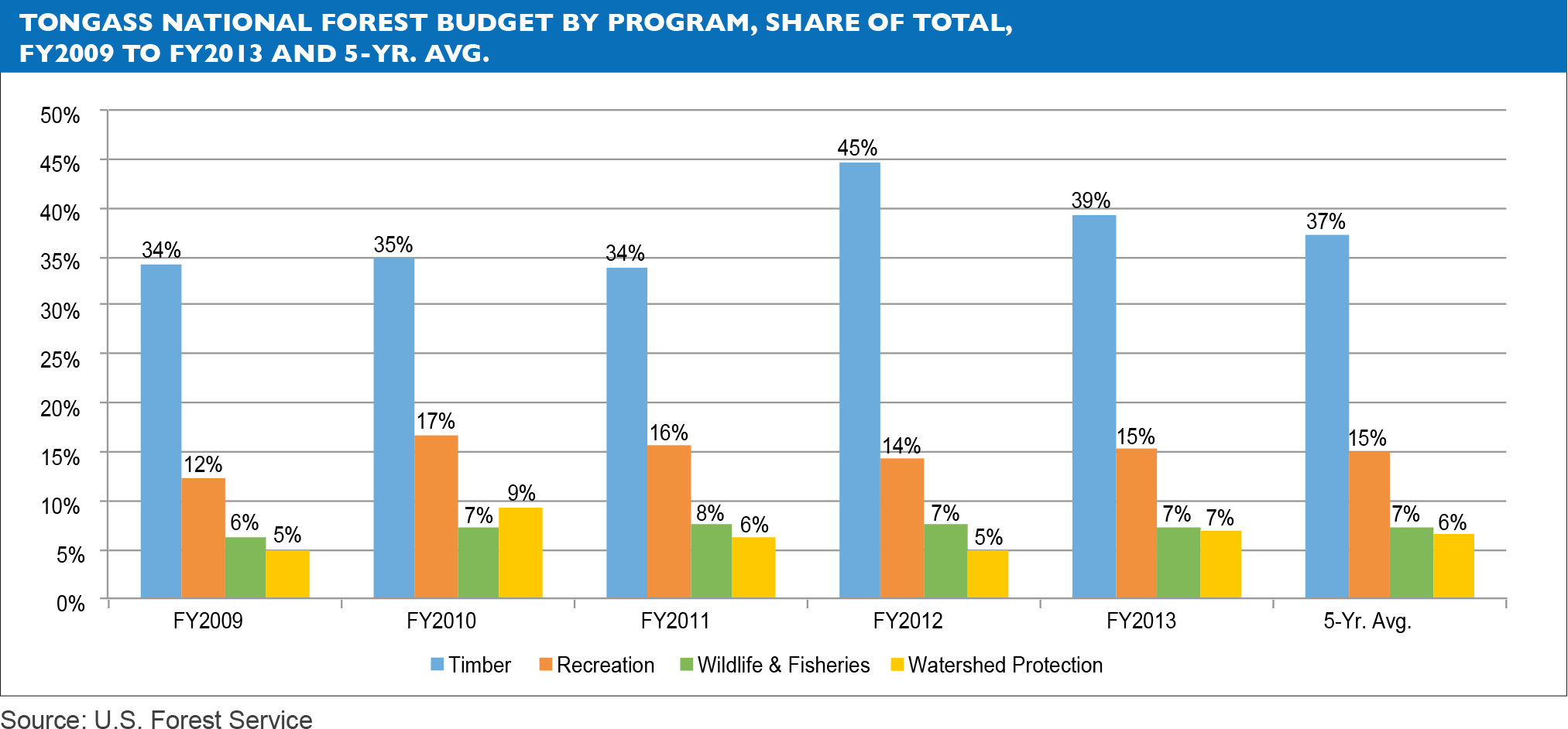

The Tongass National Forest budget and staffing were examined in detail because they provide an indicator of agency priorities. Forest Service spending on timber continues to account for the largest portion of the Tongass National Forest budget—roughly 34 to 45 percent of the budget. Since the transition was announced, expenditures on timber production show no particular trend, though timber’s share of the overall budget has increased. Despite overall staff cuts on the Tongass National Forest from FY2011 to FY2013, timber FTEs have largely held steady.

Recreation budget expenditures fell during the analysis period, though they were partially offset by increases in recreation receipts. In 2014 the Tongass National Forest announced its intention to enact future budget cuts in the recreation program—despite growing public demand for recreation activities on Forest Service lands. From FY2011 to FY2013, recreation staff declined more than any other major program on the Tongass National Forest, falling from 60 to 47 FTEs.

Tourism and Fishing, Rather Than Timber, Drive Southeast Alaska Economy

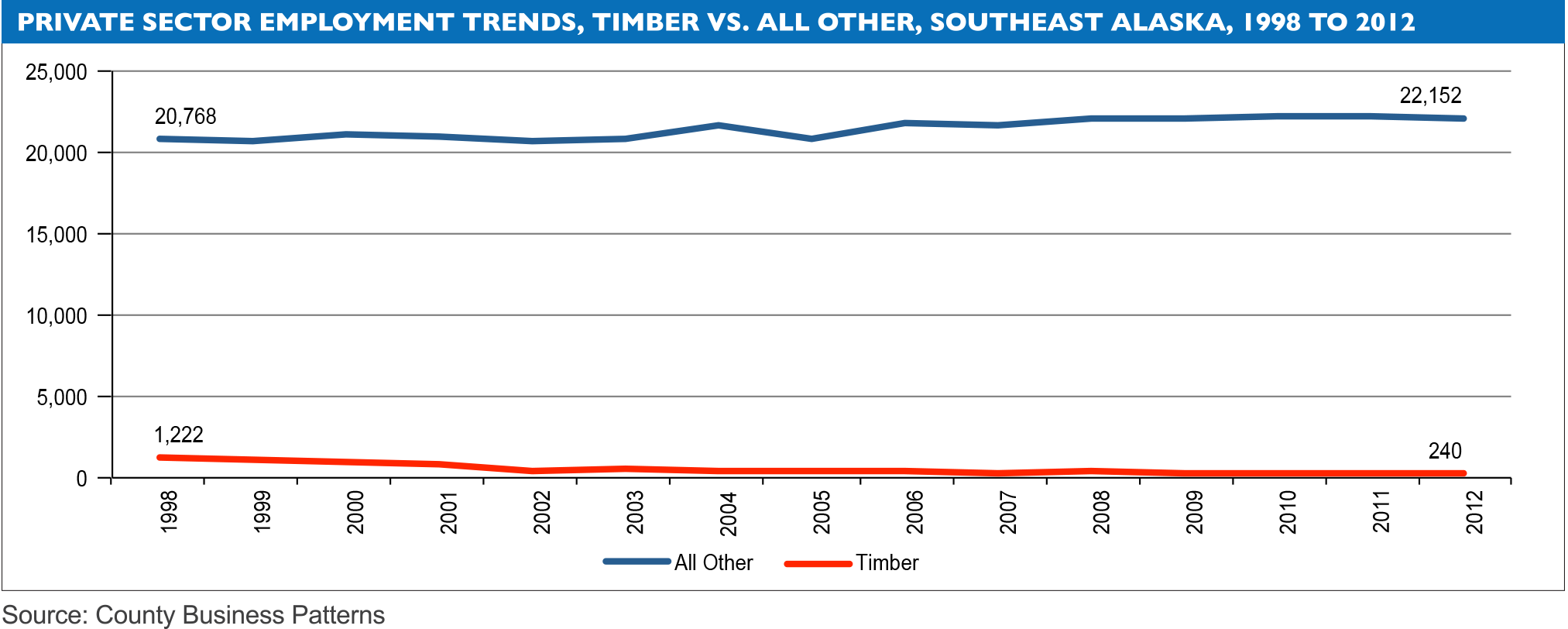

The southeast Alaska economy is no longer driven by the timber industry, which has steadily declined as a share of all private sector jobs. From 1998 to 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, regional timber jobs declined by more than 80 percent (-982 jobs), while all other private sector jobs grew by nearly seven percent (+1,384 jobs).

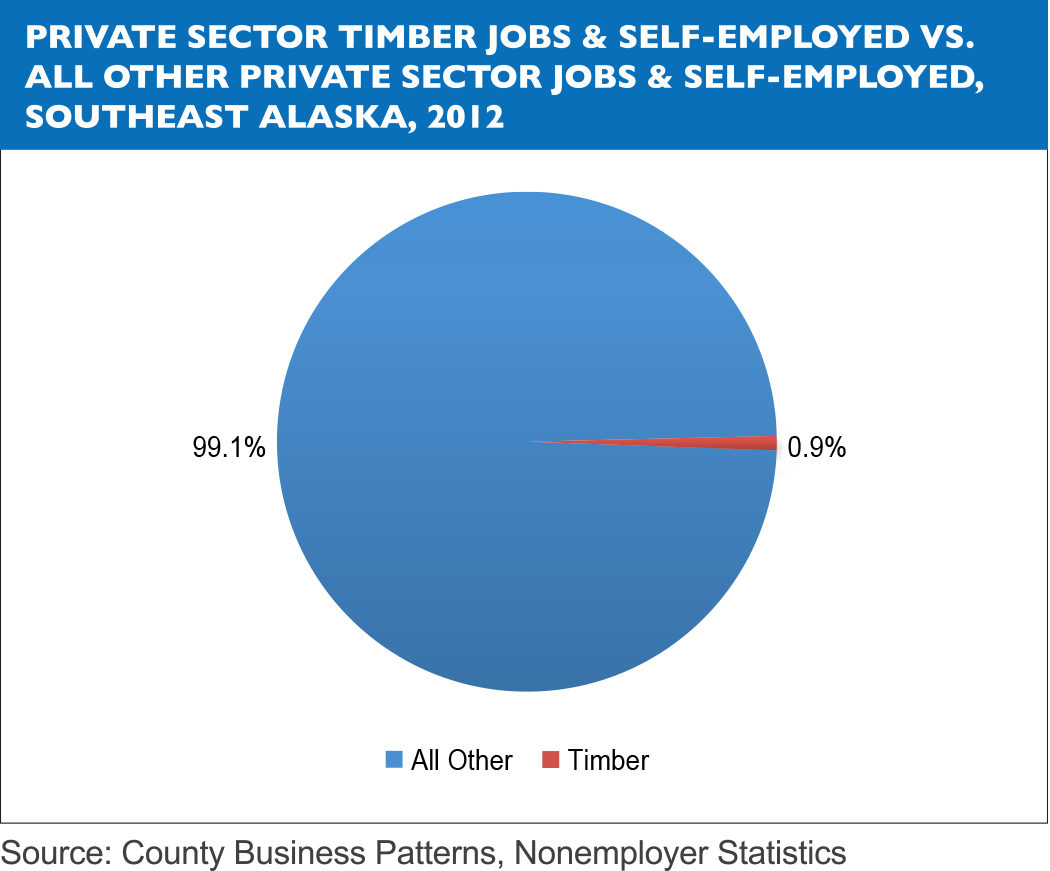

In addition to a declining number of jobs, economic data from all sources indicate that timber industry employment in southeast Alaska today is small proportion of the regional economy. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, regional timber industry jobs accounted for 1.1 percent of total private employment in 2012. An additional 41 self-employed individuals worked in the timber industry in 2012, or 0.5 percent of all self-employed people in the region—for a combined 0.9 percent of all private jobs and self-employed in southeast Alaska.

By comparison, the two largest private sectors in the region’s economy—the tourism and fishing industries—are growing. Southeast Conference reports that in 2013:

- The southeast Alaska visitor industry employed 6,707 people, is growing (+332 jobs, 5.2% change from 2012 to 2013), and accounted for 15 percent of total regional employment.

- The southeast Alaska seafood industry employed 4,252 people, is growing (+148 jobs, 3.6% change from 2012 to 2013), and accounted for nine percent of total regional employment.

The tourism and fishing industries both rely on land and water resources managed by the Tongass National Forest and directly benefit from enhancements to natural resource health, along with services and infrastructure provided by the Forest Service. Activities that degrade the pristine nature of the land, such as old growth harvesting, are likely to have adverse impacts on these important regional industries.

Narrow Focus on Old Growth Timber Sales with Subsidies Persists

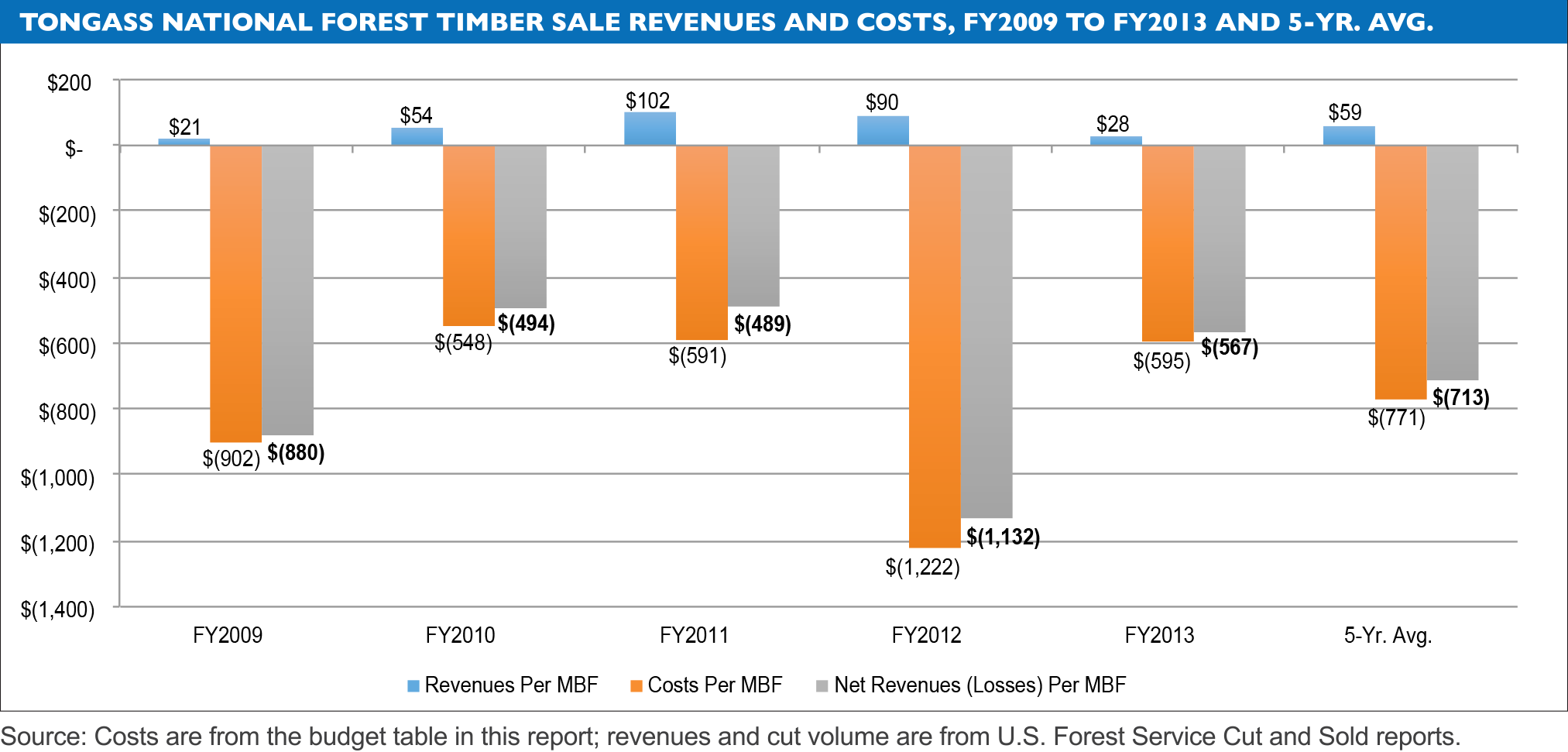

Since the Transition Framework announcement, 87 percent of timber sales proposed by the Tongass National Forest have been old growth by volume. Timber sales have consistently cost much more to prepare, access, and administer than the federal government receives for the timber. The net loss to the U.S. taxpayer has ranged from $489 to $1,132 per thousand board feet—or more than $100 million—during these years.

Earlier this year, the Forest Service awarded a 97-million board foot timber sale contract as part of the Big Thorne Project that was reportedly worth more than $6 million. But at the FY2013 average Tongass National Forest cost of $595 per MBF, the preparation and administration costs of the sale would be more than $57 million, with a net cost to the U.S. Treasury of $50 million—a nearly 10:1 expense-revenue loss ratio.

Conclusion

The allocation of scarce Tongass National Forest budget and staff resources to a minor economic sector represents a large opportunity cost for the regional economy: these resources could be repurposed, using the logic of the Transition Framework, to larger and more vibrant industries that support more jobs and communities in southeast Alaska. The casualties of this failure to seize a more promising economic trajectory are southeast Alaska’s businesses and communities, as well as the U.S. taxpayer.